Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultranationalist political ideology and movement, characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hierarchy, subordination of individual interests for the perceived good of the nation or race, and strong regimentation of society and the economy.

Victor Emmanuel III, born Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro di Savoia, was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia (1936–41) and King of the Albanians (1939–43) following the Italian invasions of Ethiopia and Albania. During his reign of nearly 46 years, which began after the assassination of his father Umberto I, the Kingdom of Italy became involved in two world wars. His reign also encompassed the birth, rise, and fall of the Fascist regime in Italy.

Umberto II was the last King of Italy. Umberto's reign lasted for 34 days, from 9 May 1946 until his formal deposition on 12 June 1946, although he had been the de facto head of state since 1944. Due to his short reign, he was nicknamed the May King.

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari, was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law, Benito Mussolini, from 1936 until 1943. During this period, he was widely seen as Mussolini's most probable successor as head of government.

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli, was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's Royal Army, primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during World War II. A dedicated fascist and prominent member of the National Fascist Party, he was a key figure in the Italian military during the reign of Victor Emmanuel III.

The Italian Social Republic, known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy, but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò, was a Nazi-German puppet state with limited diplomatic recognition that was created during the latter part of World War II. It existed from the beginning of the German occupation of Italy in September 1943 until the surrender of German troops in Italy in May 1945. The German occupation triggered widespread national resistance against it and the Italian Social Republic, leading to the Italian Civil War.

Italo Balbo was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Italian Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young age, he was sometimes seen as a possible successor to dictator Benito Mussolini.

Giacomo Matteotti was an Italian socialist politician. He was elected deputy of the Chamber of Deputies three times, in 1919, 1921 and in 1924. On 30 May 1924, he openly spoke in the Italian Parliament alleging the Italian fascists committed fraud in the 1924 general election, and denounced the violence they used to gain votes. Eleven days later, he was kidnapped and killed by fascists, age 39.

Roberto Farinacci was a leading Italian fascist politician and important member of the National Fascist Party before and during World War II, as well as one of its ardent antisemitic proponents. English historian Christopher Hibbert describes him as "slavishly pro-German".

Dino Grandi, 1st Conte di Mordano was an Italian Fascist politician, minister of justice, minister of foreign affairs and president of parliament.

This article covers the history of Italy as a monarchy and in the World Wars. The Kingdom of Italy was a state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 2 June 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and form the modern Italian Republic. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state.

Gennaro Rubino was an Italian anarchist who unsuccessfully tried to assassinate King Leopold II of Belgium.

Emilio De Bono was an Italian general, fascist activist, marshal, war criminal, and member of the Fascist Grand Council. De Bono fought in the Italo-Turkish War, the First World War and the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. He was one of the key figures behind Italy's anti-partisan policies in Libya, such as the use of poison gas and concentration camps, which resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians and have been described as genocidal.

Giovanni Giuriati was an Italian fascist politician.

Giovanni Marinelli was an Italian Fascist political leader.

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian dictator who founded and led the National Fascist Party (PNF). He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 1943, as well as Duce of Italian fascism from the establishment of the Italian Fasces of Combat in 1919 until his summary execution in 1945 by Italian partisans. As dictator of Italy and one of the principal founders of fascism, Mussolini inspired and supported the international spread of fascist movements during the inter-war period.

Pietro Tacchi Venturi was a Jesuit priest and historian who served as the unofficial liaison between Benito Mussolini, the Fascist leader of Italy from 1922 to 1943, and Popes Pius XI and Pius XII. He was also one of the architects of the 1929 Lateran Treaty, which ended the "Roman Question", and recognized the sovereignty of Vatican City, which made it an actor of international relations. A claimed attempt to assassinate Venturi with a paper knife, one year before the treaty's completion, made headlines around the world. Venturi had begun the process of reconciliation by convincing Mussolini to donate the valuable library of the Palazzo Chigi to the Vatican.

The organization officially known as Volante Rossa "Martiri Partigiani", often mentioned simply as Volante Rossa, was a clandestine antifascist paramilitary organization active in and around Milan in the postwar to the Second World War, from 1945 to 1949. Led by "tenente Alvaro", nom-de-guerre of Giulio Paggio, it was made up of communist partisans and workers who aimed with their actions to build a continuity with the wartime action of the Italian Resistance.

Fascist Italy is a term which is used to describe the Kingdom of Italy when it was governed by the National Fascist Party from 1922 to 1943 with Benito Mussolini as prime minister and dictator. The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule and they also crushed political opposition, while they simultaneously promoted economic modernization, traditional social values and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church.

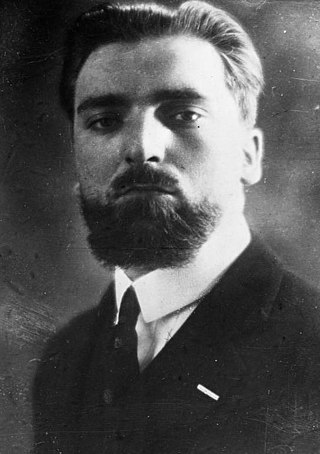

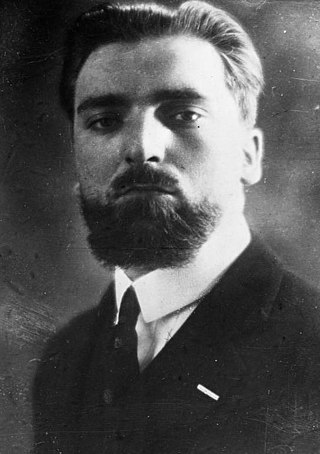

Riccardo Bauer (1896–1982) was an Italian anti-fascist journalist and political figure. He was one of the early Italians who fought against Benito Mussolini's rule. Due to his activities Bauer was imprisoned for a long time and was freed only after the collapse of the Fascist rule in 1943.