Related Research Articles

The Austrian school is a heterodox school of economic thought that advocates strict adherence to methodological individualism, the concept that social phenomena result primarily from the motivations and actions of individuals along with their self interest. Austrian-school theorists hold that economic theory should be exclusively derived from basic principles of human action.

The economic calculation problem is a criticism of using central economic planning as a substitute for market-based allocation of the factors of production. It was first proposed by Ludwig von Mises in his 1920 article "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth" and later expanded upon by Friedrich Hayek.

Eugen Ritter von Böhm-Bawerk was an economist from Austria-Hungary who made important contributions to the development of macroeconomics and to the Austrian School of Economics. He served intermittently as the Austrian Minister of Finance between 1895 and 1904. He is also noted for writing extensive criticisms of Marxism.

Friedrich Freiherr von Wieser was an early economist of the Austrian School of economics. Born in Vienna, the son of Privy Councillor Leopold von Wieser, a high official in the war ministry, he first trained in sociology and law. In 1872, the year he took his degree, he encountered Austrian-school founder Carl Menger's Grundsätze and switched his interest to economic theory. Wieser held posts at the universities of Vienna and Prague until succeeding Menger in Vienna in 1903, where along with his brother-in-law Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk he shaped the next generation of Austrian economists including Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Joseph Schumpeter in the late 1890s and early 20th century. He was the Austrian Minister of Commerce from August 30, 1917, to November 11, 1918.

In 20th-century discussions of Karl Marx's economics, the transformation problem is the problem of finding a general rule by which to transform the "values" of commodities into the "competitive prices" of the marketplace. This problem was first introduced by Marxist economist Conrad Schmidt and later dealt with by Marx in chapter 9 of the draft of volume 3 of Capital. The essential difficulty was this: given that Marx derived profit, in the form of surplus value, from direct labour inputs, and that the ratio of direct labour input to capital input varied widely between commodities, how could he reconcile this with a tendency toward an average rate of profit on all capital invested among industries, if such a tendency exists?

Marginalism is a theory of economics that attempts to explain the discrepancy in the value of goods and services by reference to their secondary, or marginal, utility. It states that the reason why the price of diamonds is higher than that of water, for example, owes to the greater additional satisfaction of the diamonds over the water. Thus, while the water has greater total utility, the diamond has greater marginal utility.

In economics, the cost-of-production theory of value is the theory that the price of an object or condition is determined by the sum of the cost of the resources that went into making it. The cost can comprise any of the factors of production and taxation.

Capital and Interest is a three-volume work on finance published by Austrian economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk (1851–1914).

The subjective theory of value (STV) is an economic theory for explaining how the value of goods and services are not only set but also how they can fluctuate over time. The contrasting system is typically known as the labor theory of value.

Johan Gustaf Knut Wicksell was a Swedish economist of the Stockholm school. He was professor at Uppsala University and Lund University.

The paradox of value is the contradiction that, although water is on the whole more useful, in terms of survival, than diamonds, diamonds command a higher price in the market. The philosopher Adam Smith is often considered to be the classic presenter of this paradox, although it had already appeared as early as Plato's Euthydemus. Nicolaus Copernicus, John Locke, John Law and others had previously tried to explain the disparity.

In economics, economic value is a measure of the benefit provided by a good or service to an economic agent, and value for money represents an assessment of whether financial or other resources are being used effectively in order to secure such benefit. Economic value is generally measured through units of currency, and the interpretation is therefore "what is the maximum amount of money a person is willing and able to pay for a good or service?” Value for money is often expressed in comparative terms, such as "better", or "best value for money", but may also be expressed in absolute terms, such as where a deal does, or does not, offer value for money.

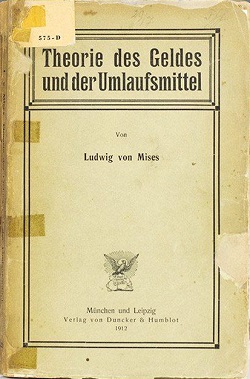

The Theory of Money and Credit is a 1912 economics book written by Ludwig von Mises, originally published in German as Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel. In it Mises expounds on his theory of the origins of money through his regression theorem, which is based on logical argumentation. It is one of the foundational works of the Misesian branch of the Austrian School of economic thought.

Frank Albert Fetter was an American economist of the Austrian School. Fetter's treatise, The Principles of Economics, contributed to an increased American interest in the Austrian School, including the theories of Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Friedrich von Wieser, and Ludwig von Mises.

Within economics, margin is a concept used to describe the current level of consumption or production of a good or service. Margin also encompasses various concepts within economics, denoted as marginal concepts, which are used to explain the specific change in the quantity of goods and services produced and consumed. These concepts are central to the economic theory of marginalism. This is a theory that states that economic decisions are made in reference to incremental units at the margin, and it further suggests that the decision on whether an individual or entity will obtain additional units of a good or service depends on the marginal utility of the product.

In economics, marginal utility describes the change in utility of one unit of a good or service. Marginal utility can be positive, negative, or zero. Negative marginal utility implies that every additional unit consumed of a commodity causes more harm than good, leading to a decrease in overall utility. In contrast, positive marginal utility indicates that every additional unit consumed increases overall utility.

Criticisms of the labor theory of value affect the historical concept of labor theory of value (LTV) which spans classical economics, liberal economics, Marxian economics, neo-Marxian economics, and anarchist economics. As an economic theory of value, LTV is widely attributed to Marx and Marxian economics despite Marx himself pointing out the contradictions of the theory, because Marx drew ideas from LTV and related them to the concepts of labour exploitation and surplus value; the theory itself was developed by Adam Smith and David Ricardo. LTV criticisms therefore often appear in the context of economic criticism, not only for the microeconomic theory of Marx but also for Marxism, according to which the working class is exploited under capitalism, while little to no focus is placed on those responsible for developing the theory.

Richard von Strigl (1891–1942) was an Austrian economist. He was considered by his colleagues one of the most brilliant Austrian economists of the interwar period. As a professor at the University of Vienna he had a decisive influence on F. A. Hayek, Fritz Machlup, Gottfried von Haberler, Oskar Morgenstern and other fourth-generation Austrian economists.

Karl Marx and the Close of His System is an 1896 book critical of the economic writings of Karl Marx by the Austrian economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. In the critique, he claims to expose some of the many flaws of the writings of Karl Marx. The text offered an early analysis of Marxist theory.

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy" or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that started in the 1950s and lasted well into the 1960s. The debate concerned the nature and role of capital goods and a critique of the neoclassical vision of aggregate production and distribution. The name arises from the location of the principals involved in the controversy: the debate was largely between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge in England and economists such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

References

- ↑ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von. "The Law of Final Utility - Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk - Mises Daily ." The Ludwig von Mises Institute . http://mises.org/daily/4637 (accessed April 29, 2011).

- ↑ von Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen, trans. George Reisman. "Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk’s “Value, Cost, and Marginal Utility”." Ludwig von Mises Institute. mises.org/pdf/asc/2002/asc8-reisman.pdf (accessed April 30, 2011).

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises. VII. Action Within The World, 1. The Law of Marginal Utility, Human Action , online version, referenced 2011-04-30.