A currency is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins. A more general definition is that a currency is a system of money in common use within a specific environment over time, especially for people in a nation state. Under this definition, the British Pound sterling (£), euros (€), Japanese yen (¥), and U.S. dollars (US$) are examples of (government-issued) fiat currencies. Currencies may act as stores of value and be traded between nations in foreign exchange markets, which determine the relative values of the different currencies. Currencies in this sense are either chosen by users or decreed by governments, and each type has limited boundaries of acceptance; i.e., legal tender laws may require a particular unit of account for payments to government agencies.

Currency substitution is the use of a foreign currency in parallel to or instead of a domestic currency.

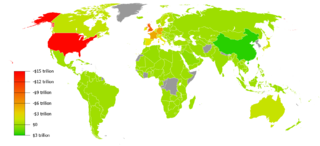

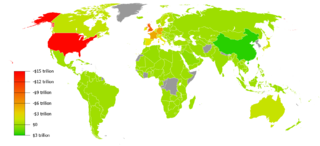

The global financial system is the worldwide framework of legal agreements, institutions, and both formal and informal economic action that together facilitate international flows of financial capital for purposes of investment and trade financing. Since emerging in the late 19th century during the first modern wave of economic globalization, its evolution is marked by the establishment of central banks, multilateral treaties, and intergovernmental organizations aimed at improving the transparency, regulation, and effectiveness of international markets. In the late 1800s, world migration and communication technology facilitated unprecedented growth in international trade and investment. At the onset of World War I, trade contracted as foreign exchange markets became paralyzed by money market illiquidity. Countries sought to defend against external shocks with protectionist policies and trade virtually halted by 1933, worsening the effects of the global Great Depression until a series of reciprocal trade agreements slowly reduced tariffs worldwide. Efforts to revamp the international monetary system after World War II improved exchange rate stability, fostering record growth in global finance.

In international economics, the balance of payments of a country is the difference between all money flowing into the country in a particular period of time and the outflow of money to the rest of the world. In other words, it is economic transactions between countries during a period of time. These financial transactions are made by individuals, firms and government bodies to compare receipts and payments arising out of trade of goods and services.

In macroeconomics and international finance, a country's current account records the value of exports and imports of both goods and services and international transfers of capital. It is one of the two components of the balance of payments, the other being the capital account. Current account measures the nation's earnings and spendings abroad and it consists of the balance of trade, net primary income or factor income and net unilateral transfers, that have taken place over a given period of time. The current account balance is one of two major measures of a country's foreign trade. A current account surplus indicates that the value of a country's net foreign assets grew over the period in question, and a current account deficit indicates that it shrank. Both government and private payments are included in the calculation. It is called the current account because goods and services are generally consumed in the current period.

In public finance, a currency board is a monetary authority which is required to maintain a fixed exchange rate with a foreign currency. This policy objective requires the conventional objectives of a central bank to be subordinated to the exchange rate target. In colonial administration, currency boards were popular because of the advantages of printing appropriate denominations for local conditions, and it also benefited the colony with the seigniorage revenue. However, after World War II many independent countries preferred to have central banks and independent currencies.

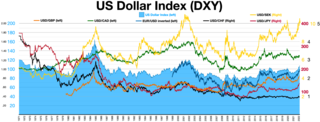

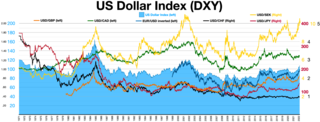

The foreign exchange market is a global decentralized or over-the-counter (OTC) market for the trading of currencies. This market determines foreign exchange rates for every currency. It includes all aspects of buying, selling and exchanging currencies at current or determined prices. In terms of trading volume, it is by far the largest market in the world, followed by the credit market.

Foreign exchange reserves are cash and other reserve assets such as gold and silver held by a central bank or other monetary authority that are primarily available to balance payments of the country, influence the foreign exchange rate of its currency, and to maintain confidence in financial markets. Reserves are held in one or more reserve currencies, nowadays mostly the United States dollar and to a lesser extent the euro.

The Bank of Korea is the central bank of South Korea and issuer of South Korean won. It was established on 12 June 1950 in Seoul, South Korea.

Money creation, or money issuance, is the process by which the money supply of a country, or an economic or monetary region, is increased. In most modern economies, money is created by both central banks and commercial banks. Money issued by central banks is a liability, typically called reserve deposits, and is only available for use by central bank account holders, which are generally large commercial banks and foreign central banks. Central banks can increase the quantity of reserve deposits directly, by making loans to account holders, purchasing assets from account holders, or by recording an asset, such as a deferred asset, and directly increasing liabilities. However, the majority of the money supply used by the public for conducting transactions is created by the commercial banking system in the form of commercial bank deposits. Bank loans issued by commercial banks expand the quantity of bank deposits.

Foreign exchange controls are various forms of controls imposed by a government on the purchase/sale of foreign currencies by residents, on the purchase/sale of local currency by nonresidents, or the transfers of any currency across national borders. These controls allow countries to better manage their economies by controlling the inflow and outflow of currency, which may otherwise create exchange rate volatility. Countries with weak and/or developing economies generally use foreign exchange controls to limit speculation against their currencies. They may also introduce capital controls, which limit foreign investment in the country.

In macroeconomics and international finance, the capital account, also known as the capital and financial account, records the net flow of investment into an economy. It is one of the two primary components of the balance of payments, the other being the current account. Whereas the current account reflects a nation's net income, the capital account reflects net change in ownership of national assets.

Capital began to flow in and out of Japan following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, but policy restricted loans from overseas. In the aftermath of World War II, Japan was a debtor nation until the mid-1960s. Subsequently, capital controls were progressively removed, in part as a result of agreements with the United States. This process led to rapid expansion of capital flows during the 1970s and especially the 1980s, when Japan became a creditor nation and the largest net investor in the world. This credit position resulted both from foreign direct investment by Japanese corporations, and portfolio investment. In particular, the rapid increase of Japan's direct investments overseas, much exceeding foreign investment in Japan, led to some tension with the US at the end of the 1980s.

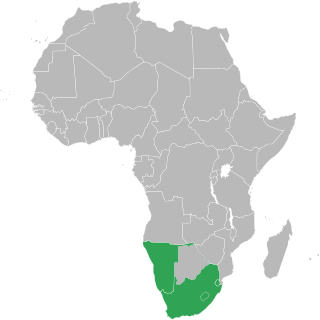

The Common Monetary Area (CMA) links South Africa, Namibia, Lesotho and Eswatini into a monetary union. The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) includes all CMA members in addition to Botswana, which replaced the rand with the pula in 1976 as a means of establishing an independent monetary policy. The CMA facilitates trade and promotes economic development between its member states.

Monetary hegemony is an economic and political concept in which a single state has decisive influence over the functions of the international monetary system. A monetary hegemon would need:

Foreign exchange risk is a financial risk that exists when a financial transaction is denominated in a currency other than the domestic currency of the company. The exchange risk arises when there is a risk of an unfavourable change in exchange rate between the domestic currency and the denominated currency before the date when the transaction is completed.

Modern monetary theory or modern money theory (MMT) is a heterodox macroeconomic theory that describes currency as a public monopoly and unemployment as evidence that a currency monopolist is overly restricting the supply of the financial assets needed to pay taxes and satisfy savings desires. According to MMT, governments do not need to worry about accumulating debt since they can pay interest by printing money. MMT argues that the primary risk once the economy reaches full employment is inflation, which acts as the only constraint on spending. When MMT says that a major role of taxes is to help offset demand rather than generate revenue, it is recognizing that taxes are a critical part of a whole suite of potential demand offsets, which also includes things like tightening financial and credit regulations to reduce bank lending, market finance, speculation and fraud.

Capital controls are residency-based measures such as transaction taxes, other limits, or outright prohibitions that a nation's government can use to regulate flows from capital markets into and out of the country's capital account. These measures may be economy-wide, sector-specific, or industry specific. They may apply to all flows, or may differentiate by type or duration of the flow.

In economics, a dual exchange rate is the occurrence of two different values of a currency for different sets of monetary transactions. One of the most common types consists of a government setting one exchange rate for specific transactions involving foreign exchange and another exchange rate governing other transactions.

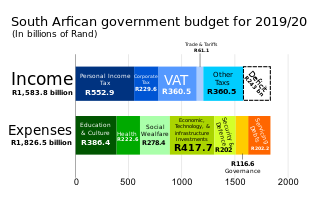

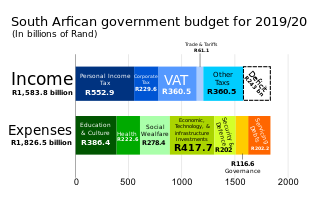

The national debt of South Africa is the total quantity of money borrowed by the Government of South Africa at any time through the issue of securities by the South African Treasury and other government agencies.