The Kalevala is a 19th-century compilation of epic poetry, compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and retaliatory voyages between the peoples of the land of Kalevala called Väinölä and the land of Pohjola and their various protagonists and antagonists, as well as the construction and robbery of the epic mythical wealth-making machine Sampo.

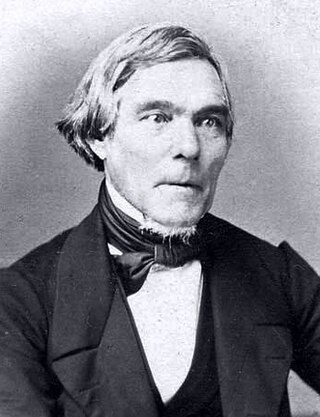

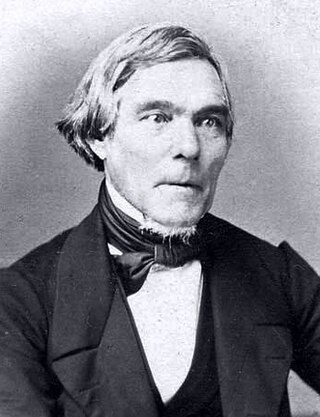

Elias Lönnrot was a Finnish polymath, physician, philosopher, poet, musician, linguist, journalist, philologist and collector of traditional Finnish oral poetry. He is best known for synthesizing the Finnish national epic, Kalevala from short ballads and lyric poems he gathered from Finnish oral tradition during several field expeditions in Finland, Russian Karelia, the Kola Peninsula and Baltic countries. In botany, he is remembered as the author of the 1860 Flora Fennica, the first scientific text written in Finnish rather than in Latin.

Finnish mythology commonly refers of the folklore of Finnish paganism, of which a modern revival is practiced by a small percentage of the Finnish people. It has many shared features with Estonian and other Finnic mythologies, but also with neighbouring Baltic, Slavic and, to a lesser extent, Norse mythologies.

Ilmarinen, a blacksmith and inventor in the Kalevala, is a god and archetypal artificer from Finnish mythology. He is immortal and capable of creating practically anything, but is portrayed as being unlucky in love. He is described as working the known metals of the time, including brass, copper, iron, gold, and silver. The great works of Ilmarinen include the crafting of the dome of the sky and the forging of the Sampo. His usual epithet in the Kalevala is seppä or seppo ("smith"), which is the source of the given name Seppo.

Hiisi is a term in Finnic mythologies, originally denoting sacred localities and later on various types of mythological entities.

Karelia is a historical province of Finland, consisting of the modern-day Finnish regions of South Karelia and North Karelia plus the historical regions of Ladoga Karelia and the Karelian isthmus, which are now in Russia. Historical Karelia also extends to the regions of Kymenlaakso, Northern Savonia and Southern Savonia (Mäntyharju).

East Karelia, also rendered as Eastern Karelia or Russian Karelia, is a name for the part of Karelia that since the Treaty of Stolbovo in 1617 has remained Eastern Orthodox and a part of Russia. It is separate from the western part of Karelia, called Finnish Karelia or historically Swedish Karelia. Most of East Karelia has become part of the Republic of Karelia within the Russian Federation. It consists mainly of the old historical regions of Viena Karjala and Aunus Karjala.

Baltic Finnic paganism, or BalticFinnic polytheism was the indigenous religion of the various of the Baltic Finnic peoples, specifically the Finns, Estonians, Võros, Setos, Karelians, Veps, Izhorians, Votes and Livonians, prior to Christianisation. It was a polytheistic religion, worshipping a number of different deities. The chief deity was the god of thunder and the sky, Ukko; other important deities included Jumala, Ahti, and Tapio. Jumala was a sky god; today, the word "Jumala" refers to a monotheistic God. Ahti was a god of the sea, waters and fish. Tapio was the god of the forest and hunting.

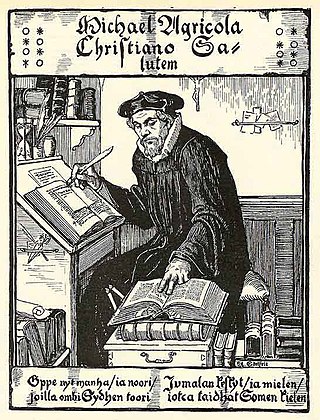

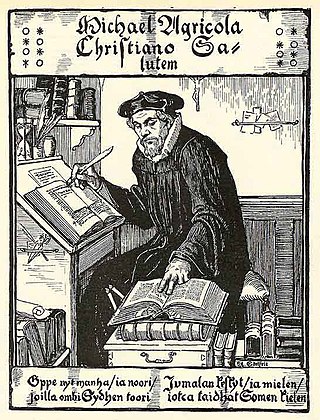

Finnish literature refers to literature written in Finland. During the European early Middle Ages, the earliest text in a Finnic language is the unique thirteenth-century Birch bark letter no. 292 from Novgorod. The text was written in Cyrillic and represented a dialect of Finnic language spoken in Russian Olonets region. The earliest texts in Finland were written in Swedish or Latin during the Finnish Middle Age. Finnish-language literature slowly developed from the sixteenth century onwards, after written Finnish was established by the bishop and Finnish Lutheran reformer Mikael Agricola (1510–1557). He translated the New Testament into Finnish in 1548.

Loviatar is a blind daughter of Tuoni, the god of death in Finnish mythology and his spouse Tuonetar, the queen of the underworld. Loviatar is regarded as a goddess of death and disease. In Runo 45 of the Kalevala, Loviatar is impregnated by a great wind and gives birth to nine sons, the Nine diseases. In other folk songs, she gives birth to a tenth child, who is a girl.

Elements of a Proto-Uralic religion can be recovered from reconstructions of the Proto-Uralic language.

The Baltic Finnic peoples, often simply referred to as the Finnic peoples, are the peoples inhabiting the Baltic Sea region in Northern and Eastern Europe who speak Finnic languages. They include the Finns, Estonians, Karelians, Veps, Izhorians, Votes, and Livonians. In some cases the Kvens, Ingrians, Tornedalians and speakers of Meänkieli are considered separate from the Finns.

Kanteletar is a collection of Finnish folk poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot. It is considered to be a sister collection to the Finnish national epic Kalevala. The poems of Kanteletar are based on the trochaic tetrameter, generally referred to as "Kalevala metre".

Tietäjä is a magically powerful figure in traditional Finnic culture, whose supernatural powers arise from his great knowledge.

Kalevala Day, known as Finnish Culture Day by its other official name, is celebrated each 28 February in honor of the Finnish national epic, Kalevala. The day is one of the official flag flying days in Finland.

Suomen kansan vanhat runot, or SKVR, is an edition of traditional Finnic-language verse containing around 100,000 different songs, and including the majority of the songs that were the sources of the Finnish epic Kalevala and related poetry. The collection is available, free, online.

Synty is an important concept in Finnish mythology. Syntysanat ('origin-words') or syntyloitsut ('origin-charms') provide an explanatory, mythical account of the origin of a phenomenon, material, or species, and were an important part of traditional Finno-Karelian culture, particularly in healing rituals. Although much in the Finnish traditional charms is paralleled elsewhere, 'the role of aetiological and cosmogonic myths' in Finnic tradition 'appears exceptional in Eurasia'. The major study remains that by Kaarle Krohn, published in 1917.

The corpus of traditional riddles from the Finnic-speaking world is fairly unitary, though eastern Finnish-speaking regions show particular influence of Russian Orthodox Christianity and Slavonic riddle culture. The Finnish for 'riddle' is arvoitus, related to the verb arvata and arpa.

Voknavolok is a rural locality (selo) under the administrative jurisdiction of the Town of Kostomuksha of the Republic of Karelia, Russia. Population: 427 (2010 Census).

Frog coffins are burials of frogs in miniature coffins in Finland for the purposes of folk magic. These coffins are known from finds secreted in churches, as well as from references to their use in folk magic at other locations.