Johann Pachelbel was a German composer, organist, and teacher who brought the south German organ schools to their peak. He composed a large body of sacred and secular music, and his contributions to the development of the chorale prelude and fugue have earned him a place among the most important composers of the middle Baroque era.

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player. Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of keyboard music in the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. A child prodigy, Frescobaldi studied under Luzzasco Luzzaschi in Ferrara, but was influenced by many composers, including Ascanio Mayone, Giovanni Maria Trabaci, and Claudio Merulo. Girolamo Frescobaldi was appointed organist of St. Peter's Basilica, a focal point of power for the Cappella Giulia, from 21 July 1608 until 1628 and again from 1634 until his death.

Antonio de Cabezón was a Spanish Renaissance composer and organist. Blind from childhood, he quickly rose to prominence as a performer and was eventually employed by the royal family. He was among the most important composers of his time and the first major Iberian keyboard composer.

A ricercar or ricercare is a type of late Renaissance and mostly early Baroque instrumental composition. The term ricercar derives from the Italian verb ricercare which means 'to search out; to seek'; many ricercars serve a preludial function to "search out" the key or mode of a following piece. A ricercar may explore the permutations of a given motif, and in that regard may follow the piece used as illustration. The term is also used to designate an etude or study that explores a technical device in playing an instrument, or singing.

Johann Jakob Froberger was a German Baroque composer, keyboard virtuoso, and organist. Among the most famous composers of the era, he was influential in developing the musical form of the suite of dances in his keyboard works. His harpsichord pieces are highly idiomatic and programmatic.

Johann Caspar Kerll was a German baroque composer and organist. He is also known as Kerl, Gherl, Giovanni Gasparo Cherll and Gaspard Kerle.

The French Organ Mass is a type of Low Mass that came into use during the Baroque era. Essentially it is a Low Mass with organ music playing throughout: part of the so-called alternatim practice.

The Eight Short Preludes and Fugues, BWV 553–560, are a collection of works for keyboard and pedal formerly attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach. They are now believed to have been composed by one of Bach's pupils, possibly Johann Tobias Krebs or his son Johann Ludwig Krebs, or by the Bohemian composer Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer.

Giovanni Girolamo Kapsperger was an Austrian-Italian virtuoso performer and composer of the early Baroque period. A prolific and highly original composer, Kapsberger is chiefly remembered today for his lute and theorbo (chitarrone) music, which was seminal in the development of these as solo instruments.

André Raison was a French Baroque composer and organist. During his lifetime he was one of the most famous French organists and an important influence on French organ music. He published two collections of organ works, in 1688 and 1714. The first contains liturgical music intended for monasteries and a preface with information on contemporary performance practice. The second contains mostly noëls.

Alessandro Poglietti was a Baroque organist and composer of unknown origin. In the second half of the 17th century Poglietti settled in Vienna, where he attained an extremely high reputation, becoming one of Leopold I's favorite composers. Poglietti held the post of court organist for 22 years from 1661 until his death during the Turkish siege that led into the Battle of Vienna.

Gottlieb Muffat, son of Georg Muffat, served as Hofscholar under Johann Fux in Vienna from 1711 and was appointed to the position of third court organist at the Hofkapelle in 1717. He acquired additional duties over time including the instruction of members of the Imperial family, among them the future Empress Maria Theresa. He was promoted to second organist in 1729 and first organist upon the accession of Maria Theresa to the throne in 1741. He retired from official duties at the court in 1763.

Jacques Brunel was a French organist and composer, active mostly in Italy.

Johann Heinrich Buttstett was a German Baroque organist and composer. Although he was Johann Pachelbel's most important pupil and one of the last major exponents of the south German organ tradition, Buttstett is best remembered for a dispute with Johann Mattheson.

Johann Ulrich Steigleder was a German Baroque composer and organist. He was the most celebrated member of the Steigleder family, which also included Adam Steigleder (1561–1633), his father, and Utz Steigleder, his grandfather.

Johann Krieger was a German composer and organist, younger brother of Johann Philipp Krieger. Born in Nuremberg, he worked at Bayreuth, Zeitz, and Greiz before settling in Zittau. He was one of the most important keyboard composers of his day, highly esteemed by, among others, George Frideric Handel. A prolific composer of church and secular music, he published several dozen of his works, and others survive in manuscript. However, hundreds more were lost when Zittau was destroyed by fire in 1757, during the Seven Years' War.

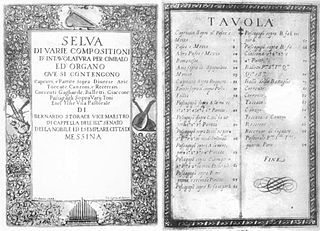

Bernardo Storace was an Italian composer. Almost nothing is known about his life; his only surviving collection of music contains numerous variation sets and represents a transitory stage between the time of Girolamo Frescobaldi and that of Bernardo Pasquini.

Il secondo libro di toccate is a collection of keyboard music by Girolamo Frescobaldi, first published in 1627. A work of immense historical importance, it includes the first known chaconne and passacaglia, as well as the earliest set of variations on an original theme. Il secondo libro di toccate is widely regarded as a high point in Frescobaldi's oeuvre.

Il Primo Libro delle Canzoni is a collection of instrumental Baroque canzonas by the Ferrarese organist and composer Girolamo Frescobaldi. It was published in two different editions in Rome in 1628, and re-issued with substantial revisions in Venice in 1634. The three editions of the Primo Libro contain a total of forty-eight canzonas for one, two, three or four instrumental voices in various combinations, all with basso continuo; as a result of revisions, sixteen of the canzonas exist in two substantially different versions.