Habeas corpus is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, to bring the prisoner to court, to determine whether the detention is lawful.

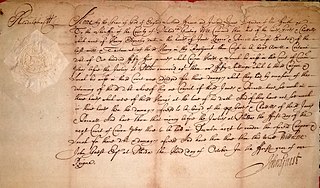

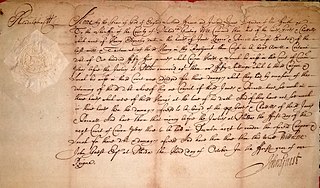

In common law, a writ is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, and Certiorari are common types of writ, but many forms exist and have existed.

A prerogative writ is a historic term for a writ that directs the behavior of another arm of government, such as an agency, official, or other court. It was originally available only to the Crown under English law, and reflected the discretionary prerogative and extraordinary power of the monarch. The term may be considered antiquated, and the traditional six comprising writs are often called the extraordinary writs and described as extraordinary remedies.

Robin Brunskill Cooke, Baron Cooke of Thorndon was a New Zealand judge and later a British Law Lord and member of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. He is widely considered one of New Zealand's most influential jurists, and is the only New Zealand judge to have sat in the House of Lords. He was a Non-Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong from 1997 to 2006.

The Supreme Court of New Zealand is the highest court and the court of last resort of New Zealand. It formally came into being on 1 January 2004 and sat for the first time on 1 July 2004. It replaced the right of appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, based in London. It was created with the passing of the Supreme Court Act 2003, on 15 October 2003. At the time, the creation of the Supreme Court and the abolition of appeals to the Privy Council were controversial constitutional changes in New Zealand. The Act was repealed on 1 March 2017 and superseded by the Senior Courts Act 2016.

The writ of coram nobis is a legal order allowing a court to correct its original judgment upon discovery of a fundamental error that did not appear in the records of the original judgment's proceedings and would have prevented the judgment from being pronounced. The term "coram nobis" is Latin for "before us" and the meaning of its full form, quae coram nobis resident, is "which [things] remain in our presence". The writ of coram nobis originated in the courts of common law in the English legal system during the sixteenth century.

The Court of Appeal of Singapore is the nation's highest court and court of final appeal. It is the upper division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the lower being the High Court. The Court of Appeal consists of the chief justice, who is the president of the Court, and the Judges of Appeal. The chief justice may ask judges of the High Court to sit as members of the Court of Appeal to hear particular cases. The seat of the Court of Appeal is the Supreme Court Building.

The Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) is a progressive non-profit legal advocacy organization based in New York City, New York, in the United States. It was founded in 1966 by Arthur Kinoy, William Kunstler and others particularly to support activists in the implementation of civil rights legislation and to achieve social justice.

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in many legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and highcourt of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of a supreme court are not subject to further review by any other court. Supreme courts typically function primarily as appellate courts, hearing appeals from decisions of lower trial courts, or from intermediate-level appellate courts.

The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 is a statute of the Parliament of New Zealand setting out the rights and fundamental freedoms of anyone subject to New Zealand law as a bill of rights. It is part of New Zealand's uncodified constitution.

The Military Commissions Act of 2006, also known as HR-6166, was an Act of Congress signed by President George W. Bush on October 17, 2006. The Act's stated purpose was "to authorize trial by military commission for violations of the law of war, and for other purposes".

In United States law, habeas corpus is a recourse challenging the reasons or conditions of a person's confinement under color of law. A petition for habeas corpus is filed with a court that has jurisdiction over the custodian, and if granted, a writ is issued directing the custodian to bring the confined person before the court for examination into those reasons or conditions. The Suspension Clause of the United States Constitution specifically included the English common law procedure in Article One, Section 9, clause 2, which demands that "The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it."

Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008), was a writ of habeas corpus submission made in a civilian court of the United States on behalf of Lakhdar Boumediene, a naturalized citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina, held in military detention by the United States at the Guantanamo Bay detention camps in Cuba. Guantanamo Bay is not formally part of the United States, and under the terms of the 1903 lease between the United States and Cuba, Cuba retained ultimate sovereignty over the territory, while the United States exercises complete jurisdiction and control. The case was consolidated with habeas petition Al Odah v. United States. It challenged the legality of Boumediene's detention at the United States Naval Station military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba as well as the constitutionality of the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Oral arguments on the combined cases were heard by the Supreme Court on December 5, 2007.

In United States law, habeas corpus is a recourse challenging the reasons or conditions of a person's detention under color of law. The Guantanamo Bay detention camp is a United States military prison located within Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. A persistent standard of indefinite detention without trial and incidents of torture led the operations of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to be challenged internationally as an affront to international human rights, and challenged domestically as a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth amendments of the United States Constitution, including the right of petition for habeas corpus. In 19 February 2002, Guantanamo detainees petitioned in federal court for a writ of habeas corpus to review the legality of their detention.

Clawson v. United States, 113 U.S. 143 (1885), was a case regarding a Utah territorial statute which authorized an appeal by a defendant in a criminal action from a final judgment of conviction, which provides that an appeal shall stay execution upon filing with the clerk a certificate of a judge that in his opinion there is probable cause for the appeal, and further provides that after conviction, a defendant who has appealed may be admitted to bail as of right when the judgment is for the payment of a fine only, and as matter of discretion in other cases, does not confer upon a defendant convicted and sentenced to pay a fine and be imprisoned the right, after appeal and filing of certificate of probable cause, to be admitted to bail except within the discretion of the court.

Chng Suan Tze v. Minister for Home Affairs is a seminal case in administrative law decided by the Court of Appeal of Singapore in 1988. The Court decided the appeal in the appellants' favour on a technical ground, but considered obiter dicta the reviewability of government power in preventive detention cases under the Internal Security Act ("ISA"). The case approved the application by the court of an objective test in the review of government discretion under the ISA, stating that all power has legal limits and the rule of law demands that the courts should be able to examine the exercise of discretionary power. This was a landmark shift from the position in the 1971 High Court decision Lee Mau Seng v. Minister of Home Affairs, which had been an authority for the application of a subjective test until it was overruled by Chng Suan Tze.

Following the common law system introduced into Hong Kong when it became a Crown colony, Hong Kong's criminal procedural law and the underlying principles are very similar to the one in the UK. Like other common law jurisdictions, Hong Kong follows the principle of presumption of innocence. This principle penetrates the whole system of Hong Kong's criminal procedure and criminal law. Viscount Sankey once described this principle as a 'golden thread'. Therefore, knowing this principle is vital for understanding the criminal procedures practised in Hong Kong.

The remedies available in Singapore administrative law are the prerogative orders – the mandatory order, prohibiting order (prohibition), quashing order (certiorari), and order for review of detention – and the declaration, a form of equitable remedy. In Singapore, administrative law is the branch of law that enables a person to challenge an exercise of power by the executive branch of the Government. The challenge is carried out by applying to the High Court for judicial review. The Court's power to review a law or an official act of a government official is part of its supervisory jurisdiction, and at its fullest may involve quashing an action or decision and ordering that it be redone or remade.

The remedies available in a Singapore constitutional claim are the prerogative orders – quashing, prohibiting and mandatory orders, and the order for review of detention – and the declaration. As the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore is the supreme law of Singapore, the High Court can hold any law enacted by Parliament, subsidiary legislation issued by a minister, or rules derived from the common law, as well as acts and decisions of public authorities, that are inconsistent with the Constitution to be void. Mandatory orders have the effect of directing authorities to take certain actions, prohibiting orders forbid them from acting, and quashing orders invalidate their acts or decisions. An order for review of detention is sought to direct a party responsible for detaining a person to produce the detainee before the High Court so that the legality of the detention can be established.

Taylor v Attorney-General[2015] NZHC 1706 is a New Zealand High Court judgment which made a formal declaration that a statute that prohibited prisoners from voting is inconsistent with the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. The action was brought by Arthur Taylor, a high-profile prison inmate. This was the first time a court had recognised that a formal declaration of inconsistency is an available remedy for statutory breaches of the Bill of Rights. Section 5 of the Bill of Rights Act states, "Subject to section 4, the rights and freedoms contained in this Bill of Rights may be subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society." In his decision, Justice Heath declared that the Electoral Amendment Act 2010 which stripped all voting rights in general elections from prisoners was an unjustified limitation on the right to vote contained in s 12 of the Bill of Rights. The Court of Appeal upheld this decision after the Attorney-General appealed the jurisdiction of the courts to make declarations of inconsistency.