Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution. It was practised as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16th century, it had risen to be the principal industry in the Basque coastal regions of Spain and France. The industry spread throughout the world, and became increasingly profitable in terms of trade and resources. Some regions of the world's oceans, along the animals' migration routes, had a particularly dense whale population, and became the targets for large concentrations of whaling ships, and the industry continued to grow well into the 20th century. The depletion of some whale species to near extinction led to the banning of whaling in many countries by 1969, and to an international cessation of whaling as an industry in the late 1980s.

The Bering Strait is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia-United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' 37" W longitude, slightly south of the Arctic Circle at about 65° 40' N latitude. The Strait is named after Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer in the service of the Russian Empire.

The Bering Sea is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Americas. It comprises a deep water basin, which then rises through a narrow slope into the shallower water above the continental shelves. The Bering Sea is named for Vitus Bering, a Danish navigator in Russian service, who, in 1728, was the first European to systematically explore it, sailing from the Pacific Ocean northward to the Arctic Ocean.

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula. It includes the Chukchi Sea, the Bering Sea, the Bering Strait, the Chukchi and Kamchatka Peninsulas in Russia as well as Alaska in the United States and the Yukon in Canada.

The Iñupiat are a group of Alaska Natives, whose traditional territory roughly spans northeast from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the northernmost part of the Canada–United States border. Their current communities include 34 villages across Iñupiat Nunaat including seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation.

The Thule or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region. The appellation "Thule" originates from the location of Thule in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer's Midden. The links between the Thule and the Inuit are biological, cultural, and linguistic.

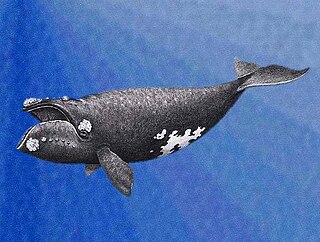

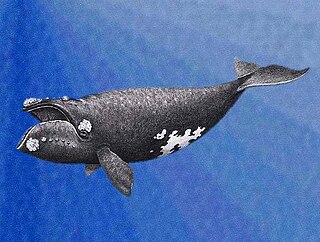

The North Pacific right whale is a very large, thickset baleen whale species that is extremely rare and endangered.

Chukchi Sea, sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, beyond which lies the Beaufort Sea. The Bering Strait forms its southernmost limit and connects it to the Bering Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The principal port on the Chukchi Sea is Uelen in Russia. The International Date Line crosses the Chukchi Sea from northwest to southeast. It is displaced eastwards to avoid Wrangel Island as well as the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug on the Russian mainland.

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately 14,060,000 km2 (5,430,000 sq mi) and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, although some oceanographers call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea. It has been described approximately as an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It is also seen as the northernmost part of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in New England. The industry peaked in 1846–1852, and New Bedford, Massachusetts, sent out its last whaler, the John R. Mantra, in 1927. The Whaling industry was engaged with the production of three different raw materials: whale oil, spermaceti oil, and whalebone. Whale oil was the result of "trying-out" whale blubber by heating in water. It was a primary lubricant for machinery, whose expansion through the Industrial Revolution depended upon before the development of petroleum-based lubricants in the second half of the 19th century. Once the prized blubber and spermaceti had been extracted from the whale, the remaining majority of the carcass was discarded.

The Fram Strait is the passage between Greenland and Svalbard, located roughly between 77°N and 81°N latitudes and centered on the prime meridian. The Greenland and Norwegian Seas lie south of Fram Strait, while the Nansen Basin of the Arctic Ocean lies to the north. Fram Strait is noted for being the only deep connection between the Arctic Ocean and the World Oceans. The dominant oceanographic features of the region are the West Spitsbergen Current on the east side of the strait and the East Greenland Current on the west.

The bowhead whale is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and the only living representative of the genus Balaena. They are the only baleen whale endemic to the Arctic and subarctic waters, and are named after their characteristic massive triangular skull, which they use to break through Arctic ice. Other common names of the species are the Greenland right whale or Arctic whale. American whalemen called them the steeple-top, polar whale, or Russia or Russian whale.

Chukotsky District is an administrative and municipal district (raion), one of the six in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the easternmost district of the autonomous okrug and Russia, and the closest part of Russia to the United States. It borders with the Chukchi Sea in the north, the Bering Sea in the east, Providensky District in the south, and the Kolyuchinskaya Bay in the west. The area of the district is 30,700 square kilometers (11,900 sq mi). Its administrative center is the rural locality of Lavrentiya. Population: 4,838 (2010 Census); 4,541 (2002 Census); 6,878 (1989 Census). The population of Lavrentiya accounts for 30.2% of the district's total population.

Providensky District is an administrative and municipal district (raion), one of the six in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is located in the northeast of the autonomous okrug, in the southern half of the Chukchi Peninsula with a northwest extension reaching almost to the Kolyuchinskaya Bay on the Arctic. It borders with Chukotsky District in the north, the Bering Sea in the east and south, and with Iultinsky District in the west. The area of the district is 26,800 square kilometers (10,300 sq mi). Its administrative center is the urban locality of Provideniya. Population: 3,923 (2010 Census); 4,660 (2002 Census); 9,778 (1989 Census). The population of Provideniya accounts for 50.2% of the district's total population.

The John H. Dunning Prize is a biennial book prize awarded by the American Historical Association for the best book in history related to the United States. The prize was established in 1929, and is regarded as one of the most prestigious national honors in American historical writing. Currently, only the author's first or second book is eligible. Laureates include Oscar Handlin, John Higham, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and Gordon Wood. The Dunning Prize has been shared five times, most recently in 1993. No award was made in 1937.

Barrow Canyon is a submarine canyon that straddles the boundary between the Beaufort and Chukchi seas. Compared to other nearby areas and the Canada Basin, the highly productive Barrow Canyon supports a diversity of marine animals and invertebrates.

Smith Bay is an estuary in the Beaufort Sea that supports a wide range of fish, birds, and marine mammals. It is located northeast of Point Barrow, Alaska. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management recognizes the southeastern portion of Barrow Canyon, which covers some, but not all, of Smith Bay, as an Environmentally Important Area.

The Pushkin House Book Prize is an annual book prize, awarded to the best non-fiction writing on Russia in the English language. The prize was inaugurated in 2013. The prize amount as of 2020 was £10,000. The advisory board for the prize is made up of Russia experts including Rodric Braithwaite, Andrew Jack, Bridget Kendall, Andrew Nurnberg, Marc Polonsky, and Douglas Smith.

Bathsheba Demuth is an environmental historian; she is the Dean’s Associate Professor of History and Environment and Society at Brown University. She specializes in the study of the Russian and North American Arctic. Her interest in this region was triggered when she moved north of the Arctic Circle in the Yukon, at the age of 18, and learned a wide range of survival skills in the taiga and tundra.

Sue E. Moore is a scientist at the University of Washington known for her research on marine mammals in the Arctic.