Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between the Massylii state in the east and the Masaesyli state in the west. During the Second Punic War, Masinissa, king of the Massylii, defeated Syphax of the Masaesyli to unify Numidia into the first unified Berber state for Numidians in present-day Algeria. The kingdom began as a sovereign state and an ally of Rome and later alternated between being a Roman province and a Roman client state.

Tanit or Tinnit was a chief deity of Ancient Carthage; she derives from a local Berber deity and the consort of Baal Hammon. As Ammon is a local Libyan deity, so is Tannit, which she represents the matriarchal aspect of Numidian society, whom the Egyptians identify as Neith and the Greeks identify as Athena. She was the goddess of Wisdom, civilization and the crafts; she is the defender of towns and homes where she is worshipped. Ancient North Africans used to put her sign on tombstones and homes to ask for protection, her main temples in Thinissut, Cirta, Lambaesis and Theveste .. She had a yearly festival in Antiquity which persists to this day in many parts of North Africa but was banned by Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, who called it a pagan festival.

A kasbah, also spelled qasbah, qasba, qasaba, or casbah, is a fortress, most commonly the citadel or fortified quarter of a city. It is also equivalent to the term alcazaba in Spanish, which is derived from the same Arabic word. By extension, the term can also refer to a medina quarter, particularly in Algeria. In various languages, the Arabic word, or local words borrowed from the Arabic word, can also refer to a settlement, a fort, a watchtower, or a blockhouse.

The Chaoui people or Shawyia are a Berber ethnic group native to the Aurès region in northeastern Algeria.

The Haha or Iḥaḥan is a Moroccan confederation of Masmouda Berber tribes in the Western High Atlas in Morocco. They identify themselves as a tribal confederacy of the Chleuh people, and speak the Shilha language. Their region stretches along from the city of Essaouira south to the Souss Valley, mainly on the Atlantic coast.

Gabriel Camps was a French archaeologist and social anthropologist, the founder of the Encyclopédie berbère and is considered a prestigious scholar on the history of the Berber people.

Antalas was a Berber tribal leader who played a major role in the wars of the Byzantine Empire against the Berber tribes in Africa. Antalas and his tribe, the Frexes initially served the Byzantines as allies, but after 544 switched sides. With the final Byzantine victory in his and his tribe once again became Byzantine subjects. The main sources on his life are the epic poem Iohannis of Flavius Cresconius Corippus and the Histories of the Wars of Procopius of Caesarea.

Bilta also known as Balta or Balţah, is an antique town in northern Tunisia, close to Mateur in today's Bizerte governorate. Its name comes from the Numidian language (Lybico-Berber) root BLT, meaning, filled with water.

Mastanabal was one of three legitimate sons of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in, present day Algeria, North Africa. The three brothers were appointed by Scipio Aemilianus Africanus to rule Numidia after Masinissa's death.

An agadir is a fortified communal granary found in the Maghreb.

Mohamed Ajahud, widely known as Mohamed Demsiri, was a Moroccan singer-poet (ṛṛays) and rebab player. He sang in Shilha. He is considered to be the most representative modern classical singer of amarg ajdid "the new generation of singers".

The Battle of Tabarka was a military engagement fought between the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate and Dihya, a Berber queen. The battle took place near the city of Tabarka, Tunisia, in either 701, 702 or 703 AD. The battle resulted in a major victory for the Umayyads and the end of organized Berber resistance to the caliphate.

The Crusade of Tedelis was a major conflict within the overarching struggle between the Crown of Aragon and the Kingdom of Tlemcen in the late 14th century.

The Agadez Cross is the most popular category of Saharan Berber jewelry made especially by the Tuareg people of Niger. Only a few of these pieces of jewelry exactly resemble a cross. For most of them, it is a pendant with a varied silhouette, related either to a cross (tanaghilt), or to a form of plate or shield (talhakim). The former is made of stone or copper. The blacksmiths generally use silver and the so-called "lost wax" casting process without ever hammering the metal.

Ikjan is a former town near the present-day town of Beni Aziz in Algeria. Between 902 and 909 it served as the base and capital of the Kutama Berbers led by the dā'ī (missionary) Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i, who had founded an Isma'ili Shi'a state in the region on behalf of the Fatimid cause. This new movement rose in opposition to the Aghlabid dynasty, which ruled the region of Ifriqiya formally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliphs. The site of Ikjan was considered impregnable. In 909 Abu Abdallah and the Kutama armies finally overthrew the Aghlabids and set themselves up in Raqqada, laying the foundations for the Fatimid Caliphate, which was formally established with the enthronement of the first caliph, Abd Allah al-Mahdi, later that year.

Jewellery of the Berber cultures is a historical style of traditional jewellery that was worn by women mainly in rural areas of the Maghreb region in North Africa and inhabited by Indigenous Berber people. Following long social and cultural traditions, Berber or other silversmiths in Morocco, Algeria and neighbouring countries created intricate jewellery with distinct regional variations. In many towns and cities, there were Jewish silversmiths, who produced both jewellery in specific Berber styles as well as in other styles, adapting to changing techniques and artistic innovations.

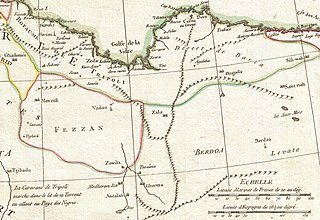

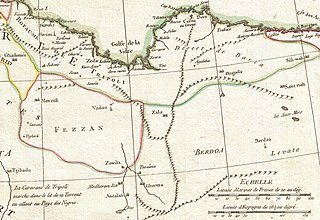

Awlad Muhammad was a tribe that ruled over the Fezzan region from 1550 to 1812. At their height, their domain extended from Sokna in the north to Murzuq in the south.

Banu Khattab was a wealthy Ibadi dynasty of Hawwara origin that thrived off of the Trans-Saharan slave trade. It ruled over Zawila and the surrounding oases in the Fezzan region from 918/919 until 1172–1177 when it was sacked and conquered by the Armenian-Mamluk Qaraqush. The instability created by Qaraqush was exploited by the Kanem, who under the reign of Dunama Dabbalemi had seized control of the Fezzan, establishing a new capital at Traghan, a few miles west of Zawila.

The Ourferdjouma or Urfedjouma, Warfajuma were a large Nefzaoua Sufrite Berber tribe. After capturing Kairouan in 757-758 from the Fihrids, the Ourferdjouma plundered the city and massacred the population. These atrocities and the desecration of the Grand Mosque of Kairouan provoked the Ibadi Berbers who after capturing Tripoli, occupied Kairouan in 758 putting an end to their terror.