Related Research Articles

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías was a Venezuelan politician and military officer who served as the 52nd president of Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013, except for a brief period of forty-seven hours in 2002. Chávez was also leader of the Fifth Republic Movement political party from its foundation in 1997 until 2007, when it merged with several other parties to form the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), which he led until 2012.

María de los Ángeles Félix Güereña was a Mexican actress and singer. Along with Pedro Armendáriz and Dolores del Río, she was one of the most successful figures of Latin American cinema in the 1940s and 1950s. Considered one of the most beautiful actresses of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, her strong personality and taste for finesse garnered her the title of diva early in her career. She was known as La Doña, a name derived from her character in Doña Bárbara (1943), and María Bonita, thanks to the anthem composed exclusively for her as a wedding gift by her second husband, Agustín Lara. Her acting career consists of 47 films made in Mexico, Spain, France, Italy and Argentina.

Women's cinema primarily describes cinematic works directed by women filmmakers. The works themselves do not have to be stories specifically about women, and the target audience can be varied.

The absence of women from the canon of Western art has been a subject of inquiry and reconsideration since the early 1970s. Linda Nochlin's influential 1971 essay, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?", examined the social and institutional barriers that blocked most women from entering artistic professions throughout history, prompted a new focus on women artists, their art and experiences, and contributed inspiration to the Feminist art movement. Although women artists have been involved in the making of art throughout history, their work, when compared to that of their male counterparts, has been often obfuscated, overlooked and undervalued. The Western canon has historically valued men's work over women's and attached gendered stereotypes to certain media, such as textile or fiber arts, to be primarily associated with women.

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

María Corina Machado Parisca is a Venezuelan opposition politician and industrial engineer who served as an elected member of the National Assembly of Venezuela from 2011 to 2014. Machado entered politics in 2002 as the founder and leader of the vote-monitoring group Súmate, alongside Alejandro Plaz. In 2018, she was listed as one of BBC's 100 Women. Machado is regarded as a leading figure of the Venezuelan opposition; the Nicolás Maduro government in Venezuela has banned Machado from leaving Venezuela.

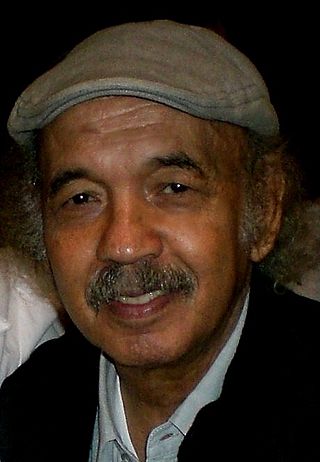

Jacobo Borges is a contemporary, neo-figurative Venezuelan artist. His curiosity for exploring different mediums made him a painter, drawer, film director, stage designer and plastic artist. Known for his ever-evolving style, there is one constant principle that unites his work: "the search for the creation of space somewhere between dreams and reality where everything has happened, happens, and may happen." His theoretical approach and unique, innovative technique has won him acclaim all over the world. He has had solo exhibitions in France, Germany, Austria, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Britain and the United States. Today, he is considered one of the most accomplished artist of Latin America. His oeuvre includes a rich body of paintings, a film directed in 1969, and a book The Great Mountain and Its Era, published in 1979. In 1982, a biography by Dore Ashton, called Jacobo Borges, was published in English and Spanish.

The record of human rights in Venezuela has been criticized by human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Concerns include attacks against journalists, political persecution, harassment of human rights defenders, poor prison conditions, torture, extrajudicial executions by death squads, and forced disappearances.

The cinema of Venezuela is the production and industry of filmmaking in Venezuela. Venezuelan cinema has been characterised from its outset as propaganda, partially state-controlled and state-funded, commercial cinema. The nation has seen a variety of successful films, which have reaped several international awards. Still, in terms of quality, it is said that though "we can point to specific people who have made great films in Venezuela [and] a couple of great moments in the history of Venezuelan cinema, [...] those have been exceptions". In the 21st century, Venezuelan cinema has seen more independence from the government, but has still been described as recently as 2017 to be at least "influenced" by the state.

Science and technology in Venezuela includes research based on exploring Venezuela's diverse ecology and the lives of its indigenous peoples.

The status of women in Mexico has changed significantly over time. Until the twentieth century, Mexico was an overwhelmingly rural country, with rural women's status defined within the context of the family and local community. With urbanization beginning in the sixteenth century, following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, cities have provided economic and social opportunities not possible within rural villages. Roman Catholicism in Mexico has shaped societal attitudes about women's social role, emphasizing the role of women as nurturers of the family, with the Virgin Mary as a model. Marianismo has been an ideal, with women's role as being within the family under the authority of men. In the twentieth century, Mexican women made great strides towards a more equal legal and social status. In 1953 women in Mexico were granted the right to vote in national elections.

Gender equality is established in the constitution of Venezuela and the country is a signatory of the United Nations's Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. However, women in the history of Venezuela have played asymmetrical roles in society compared to men. Notable women have participated in the political history since the Venezuelan War of Independence in the 19th century, but universal suffrage was not granted until 1947.

Feminism in Mexico is the philosophy and activity aimed at creating, defining, and protecting political, economic, cultural, and social equality in women's rights and opportunities for Mexican women. Rooted in liberal thought, the term feminism came into use in late nineteenth-century Mexico and in common parlance among elites in the early twentieth century. The history of feminism in Mexico can be divided chronologically into a number of periods with issues. For the conquest and colonial eras, some figures have been re-evaluated in the modern era and can be considered part of the history of feminism in Mexico. At the time of independence in the early nineteenth century, there were demands that women be defined as citizens. The late nineteenth century saw the explicit development of feminism as an ideology. Liberalism advocated secular education for both girls and boys as part of a modernizing project, and women entered the workforce as teachers. Those women were at the forefront of feminism, forming groups that critiqued existing treatment of women in the realms of legal status, access to education, and economic and political power. More scholarly attention is focused on the Revolutionary period (1915–1925), although women's citizenship and legal equality were not explicitly issues for which the revolution was fought. The Second Wave and the post-1990 period have also received considerable scholarly attention. Feminism has advocated for the equality of men and women, but middle-class women took the lead in the formation of feminist groups, the founding of journals to disseminate feminist thought, and other forms of activism. Working-class women in the modern era could advocate within their unions or political parties. The participants in the Mexico 68 clashes who went on to form that generation's feminist movement were predominantly students and educators. The advisers who established themselves within the unions after the 1985 earthquakes were educated women who understood the legal and political aspects of organized labor. What they realized was that to form a sustained movement and attract working-class women to what was a largely middle-class movement, they needed to utilize workers' expertise and knowledge of their jobs to meld a practical, working system. In the 1990s, women's rights in indigenous communities became an issue, particularly in the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas. Reproductive rights remain an ongoing issue, particularly since 1991, when the Catholic Church in Mexico was no longer constitutionally restricted from being involved in politics.

Colectivos are far-left Venezuelan armed paramilitary groups that support the Bolivarian government, the Great Patriotic Pole (GPP) political alliance and Venezuela's ruling party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). Colectivo has become an umbrella term for irregular armed groups that operate in poverty-stricken areas.

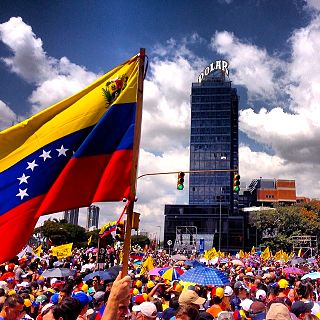

The 2014 Venezuelan protests began in February 2014 when hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested due to high levels of criminal violence, inflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods because of policies created the Venezuelan government. The protests have lasted for several months and events are listed below according to the month they had happened.

In 2014, a series of protests, political demonstrations, and civil insurrection began in Venezuela due to the country's high levels of urban violence, inflation, and chronic shortages of basic goods attributed to economic policies such as strict price controls. Mass protesting began in earnest in February following the attempted rape of a student on a university campus in San Cristóbal. Subsequent arrests and killings of student protesters spurred their expansion to neighboring cities and the involvement of opposition leaders. The year's early months were characterized by large demonstrations and violent clashes between protesters and government forces that resulted in nearly 4,000 arrests and 43 deaths, including both supporters and opponents of the government.

The 2017 Venezuelan protests began in late January following the abandonment of Vatican-backed dialogue between the Bolivarian government and the opposition. The series of protests originally began in February 2014 when hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested due to high levels of criminal violence, inflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods because of policies created by the Venezuelan government though the size of protests had decreased since 2014. Following the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis, protests began to increase greatly throughout Venezuela.

Women in PSOE in Francoist Spain had been involved in important socialist activism since the 1930s, including behind the scenes during the Asturian miners' strike of 1934, even as the party offered few leadership roles to women and address the issues of women. During the Civil War, the party was one of the few left wing actors to reject the idea of women on the front, believing women instead should take care of the home.

References

- 1 2 3 "Franca Donda (Grupo Miércoles)".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dagnino, Maruja. "Franca Donda". In Transparencia Venezuela (ed.). 20 mujeres venezolanas del siglo XX (PDF). pp. 49–54. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ↑ "Los Movimientos Feministas en Venezuela 1968 – 1985. Una perspectiva histórica" (PDF).