Isaac Newton's rotating bucket argument was designed to demonstrate that true rotational motion cannot be defined as the relative rotation of the body with respect to the immediately surrounding bodies. It is one of five arguments from the "properties, causes, and effects" of "true motion and rest" that support his contention that, in general, true motion and rest cannot be defined as special instances of motion or rest relative to other bodies, but instead can be defined only by reference to absolute space. Alternatively, these experiments provide an operational definition of what is meant by "absolute rotation", and do not pretend to address the question of "rotation relative to what?" General relativity dispenses with absolute space and with physics whose cause is external to the system, with the concept of geodesics of spacetime.

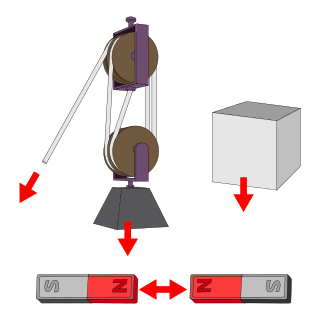

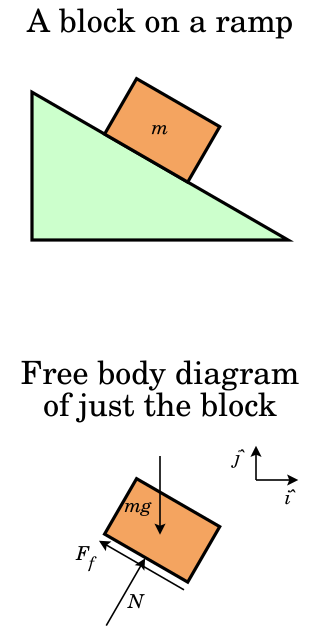

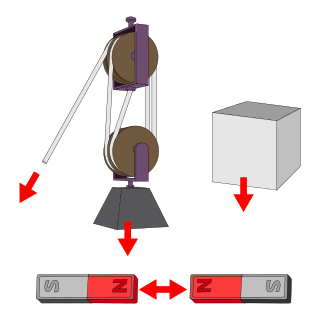

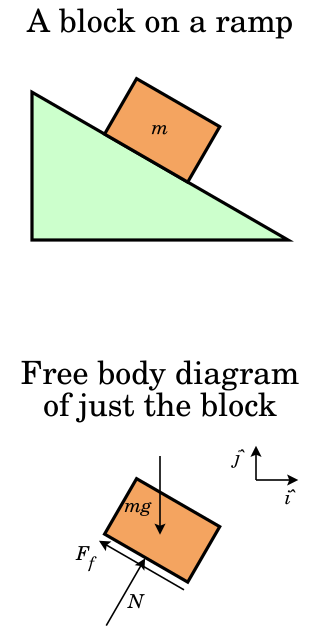

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an object to change its velocity, i.e., to accelerate, meaning a change in speed or direction, unless counterbalanced by other forces. The concept of force makes the everyday notion of pushing or pulling mathematically precise. Because the magnitude and direction of a force are both important, force is a vector quantity. The SI unit of force is the newton (N), and force is often represented by the symbol F.

In theories of quantum gravity, the graviton is the hypothetical quantum of gravity, an elementary particle that mediates the force of gravitational interaction. There is no complete quantum field theory of gravitons due to an outstanding mathematical problem with renormalization in general relativity. In string theory, believed by some to be a consistent theory of quantum gravity, the graviton is a massless state of a fundamental string.

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference is a frame of reference not undergoing any acceleration. It is a frame in which an isolated physical object—an object with zero net force acting on it—is perceived to move with a constant velocity or, equivalently, it is a frame of reference in which Newton's first law of motion holds. All inertial frames are in a state of constant, rectilinear motion with respect to one another; in other words, an accelerometer moving with any of them would detect zero acceleration. It has been observed that celestial objects which are far away from other objects and which are in uniform motion with respect to the cosmic microwave background radiation maintain such uniform motion.

The tidal force or tide-generating force is a gravitational effect that stretches a body along the line towards and away from the center of mass of another body due to spatial variations in strength in gravitational field from the other body. It is responsible for the tides and related phenomena, including solid-earth tides, tidal locking, breaking apart of celestial bodies and formation of ring systems within the Roche limit, and in extreme cases, spaghettification of objects. It arises because the gravitational field exerted on one body by another is not constant across its parts: the nearer side is attracted more strongly than the farther side. The difference is positive in the near side and negative in the far side, which causes a body to get stretched. Thus, the tidal force is also known as the differential force, residual force, or secondary effect of the gravitational field.

A wormhole is a hypothetical structure connecting disparate points in spacetime, and is based on a special solution of the Einstein field equations.

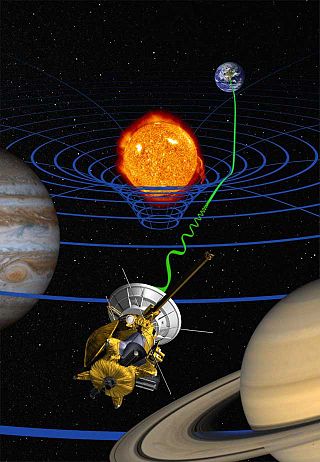

In physics, gravity (from Latin gravitas 'weight') is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things that have mass. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong interaction, 1036 times weaker than the electromagnetic force and 1029 times weaker than the weak interaction. As a result, it has no significant influence at the level of subatomic particles. However, gravity is the most significant interaction between objects at the macroscopic scale, and it determines the motion of planets, stars, galaxies, and even light.

A gravitational singularity, spacetime singularity or simply singularity is a condition in which gravity is predicted to be so intense that spacetime itself would break down catastrophically. As such, a singularity is by definition no longer part of the regular spacetime and cannot be determined by "where" or "when". Gravitational singularities exist at a junction between general relativity and quantum mechanics; therefore, the properties of the singularity cannot be described without an established theory of quantum gravity. Trying to find a complete and precise definition of singularities in the theory of general relativity, the current best theory of gravity, remains a difficult problem. A singularity in general relativity can be defined by the scalar invariant curvature becoming infinite or, better, by a geodesic being incomplete.

Newton's laws of motion are three laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

- A body remains at rest, or in motion at a constant speed in a straight line, unless acted upon by a force.

- The net force on a body is equal to the body's acceleration multiplied by its mass or, equivalently, the rate at which the body's momentum changes with time.

- If two bodies exert forces on each other, these forces have the same magnitude but opposite directions.

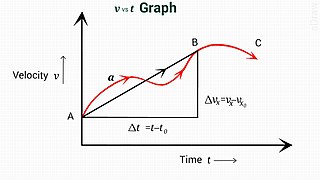

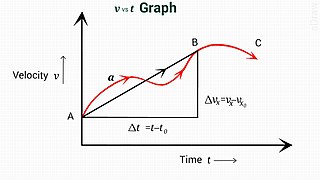

In physics, equations of motion are equations that describe the behavior of a physical system in terms of its motion as a function of time. More specifically, the equations of motion describe the behavior of a physical system as a set of mathematical functions in terms of dynamic variables. These variables are usually spatial coordinates and time, but may include momentum components. The most general choice are generalized coordinates which can be any convenient variables characteristic of the physical system. The functions are defined in a Euclidean space in classical mechanics, but are replaced by curved spaces in relativity. If the dynamics of a system is known, the equations are the solutions for the differential equations describing the motion of the dynamics.

In Newtonian physics, free fall is any motion of a body where gravity is the only force acting upon it. In the context of general relativity, where gravitation is reduced to a space-time curvature, a body in free fall has no force acting on it.

In mathematical physics, a closed timelike curve (CTC) is a world line in a Lorentzian manifold, of a material particle in spacetime, that is "closed", returning to its starting point. This possibility was first discovered by Willem Jacob van Stockum in 1937 and later confirmed by Kurt Gödel in 1949, who discovered a solution to the equations of general relativity (GR) allowing CTCs known as the Gödel metric; and since then other GR solutions containing CTCs have been found, such as the Tipler cylinder and traversable wormholes. If CTCs exist, their existence would seem to imply at least the theoretical possibility of time travel backwards in time, raising the spectre of the grandfather paradox, although the Novikov self-consistency principle seems to show that such paradoxes could be avoided. Some physicists speculate that the CTCs which appear in certain GR solutions might be ruled out by a future theory of quantum gravity which would replace GR, an idea which Stephen Hawking labeled the chronology protection conjecture. Others note that if every closed timelike curve in a given space-time passes through an event horizon, a property which can be called chronological censorship, then that space-time with event horizons excised would still be causally well behaved and an observer might not be able to detect the causal violation.

In physics and engineering, a free body diagram is a graphical illustration used to visualize the applied forces, moments, and resulting reactions on a body in a given condition. It depicts a body or connected bodies with all the applied forces and moments, and reactions, which act on the body(ies). The body may consist of multiple internal members, or be a compact body. A series of free bodies and other diagrams may be necessary to solve complex problems. Sometimes in order to calculate the resultant force graphically the applied forces are arranged as the edges of a polygon of forces or force polygon.

Absolute space and time is a concept in physics and philosophy about the properties of the universe. In physics, absolute space and time may be a preferred frame.

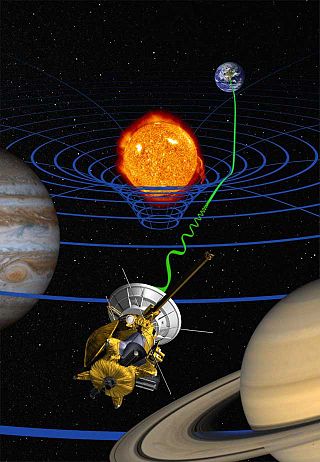

General relativity is a theory of gravitation developed by Albert Einstein between 1907 and 1915. The theory of general relativity says that the observed gravitational effect between masses results from their warping of spacetime.

In theoretical physics, a local reference frame refers to a coordinate system or frame of reference that is only expected to function over a small region or a restricted region of space or spacetime.

The mathematics of general relativity is complex. In Newton's theories of motion, an object's length and the rate at which time passes remain constant while the object accelerates, meaning that many problems in Newtonian mechanics may be solved by algebra alone. In relativity, however, an object's length and the rate at which time passes both change appreciably as the object's speed approaches the speed of light, meaning that more variables and more complicated mathematics are required to calculate the object's motion. As a result, relativity requires the use of concepts such as vectors, tensors, pseudotensors and curvilinear coordinates.

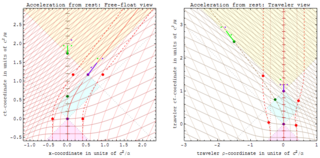

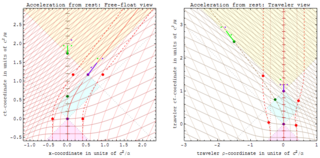

In relativity theory, proper acceleration is the physical acceleration experienced by an object. It is thus acceleration relative to a free-fall, or inertial, observer who is momentarily at rest relative to the object being measured. Gravitation therefore does not cause proper acceleration, because the same gravity acts equally on the inertial observer. As a consequence, all inertial observers always have a proper acceleration of zero.

The geodetic effect represents the effect of the curvature of spacetime, predicted by general relativity, on a vector carried along with an orbiting body. For example, the vector could be the angular momentum of a gyroscope orbiting the Earth, as carried out by the Gravity Probe B experiment. The geodetic effect was first predicted by Willem de Sitter in 1916, who provided relativistic corrections to the Earth–Moon system's motion. De Sitter's work was extended in 1918 by Jan Schouten and in 1920 by Adriaan Fokker. It can also be applied to a particular secular precession of astronomical orbits, equivalent to the rotation of the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector.

The two-body problem in general relativity is the determination of the motion and gravitational field of two bodies as described by the field equations of general relativity. Solving the Kepler problem is essential to calculate the bending of light by gravity and the motion of a planet orbiting its sun. Solutions are also used to describe the motion of binary stars around each other, and estimate their gradual loss of energy through gravitational radiation.