Related Research Articles

The Radical Party, officially the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party, is a liberal and social-liberal political party in France. Since 1971, to prevent confusion with the Radical Party of the Left (PRG), it has also been referred to as Parti radical valoisien, after its headquarters on the rue de Valois. The party's name has been variously abbreviated to PRRRS, Rad, PR and PRV. Founded in 1901, the PR is the oldest active political party in France.

The Popular Front was an alliance of left-wing movements in France, including the French Communist Party (PCF), the socialist SFIO and the Radical-Socialist Republican Party, during the interwar period. Three months after the victory of the Spanish Popular Front, the Popular Front won the May 1936 legislative election, leading to the formation of a government first headed by SFIO leader Léon Blum and composed of republican and SFIO ministers.

Jacques Doriot was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

Marcel Déat was a French politician. Initially a socialist and a member of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), he led a breakaway group of right-wing Neosocialists out of the SFIO in 1933. During the occupation of France by Nazi Germany, he founded the collaborationist National Popular Rally (RNP). In 1944, he became Minister of Labour and National Solidarity in Pierre Laval's government in Vichy, before escaping to the Sigmaringen enclave along with Vichy officials after the Allied landings in Normandy. Condemned in absentia for collaborationism, he died while still in hiding in Italy.

Neosocialism was a political faction that existed in France and Belgium during the 1930s and which included several revisionist tendencies in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO).

The Third Position is a set of neo-fascist political ideologies that were first described in Western Europe following the Second World War. Developed in the context of the Cold War, it developed its name through the claim that it represented a third position between the capitalism of the Western Bloc and the communism of the Eastern Bloc.

The French Popular Party was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

The French Social Party was a French nationalist political party founded in 1936 by François de La Rocque, following the dissolution of his Croix-de-Feu league by the Popular Front government. France's first right-wing mass party, prefiguring the rise of Gaullism after the Second World War, it experienced considerable initial success but disappeared in the wake of the fall of France in 1940 and was not refounded after the war.

The 6 February 1934 crisis was an anti-parliamentarist street demonstration in Paris organized by multiple far-right leagues that culminated in a riot on the Place de la Concorde, near the building used for the French National Assembly. The police shot and killed 17 people, nine of whom were far-right protesters. It was one of the major political crises during the Third Republic (1870–1940). Leftist Frenchmen claimed it was an attempt to organize a fascist coup d'état. According to historian Joel Colton, "The consensus among scholars is that there was no concerted or unified design to seize power and that the leagues lacked the coherence, unity, or leadership to accomplish such an end."

The Democratic Alliance, originally called Democratic Republican Alliance, was a French political party created in 1901 by followers of Léon Gambetta such as Raymond Poincaré, who would be president of the Council in the 1920s. The party was originally formed as a centre-left gathering of moderate liberals, independent Radicals who rejected the new left-leaning Radical-Socialist Party, and Opportunist Republicans, situated at the political centre and to the right of the newly formed Radical-Socialist Party. However, after World War I and the parliamentary disappearance of monarchists and Bonapartists it quickly became the main centre-right party of the Third Republic. It was part of the National Bloc right-wing coalition which won the elections after the end of the war. The ARD successively took the name "Democratic Republican Party", and then "Social and Republican Democratic Party", before becoming again the AD.

The far-right leagues were several French far-right movements opposed to parliamentarism, which mainly dedicated themselves to military parades, street brawls, demonstrations and riots. The term ligue was often used in the 1930s to distinguish these political movements from parliamentary parties. After having appeared first at the end of the 19th century, during the Dreyfus affair, they became common in the 1920s and 1930s, and famously participated in the 6 February 1934 crisis and riots which overthrew the second Cartel des gauches, i.e. the center-left coalition government led by Édouard Daladier.

The far-right tradition in France finds its origins in the Third Republic with Boulangism and the Dreyfus affair. In the 1880s, General Georges Boulanger, called "General Revenge", championed demands for military revenge against Imperial Germany as retribution for the defeat and fall of the Second French Empire during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). This stance, known as revanchism, began to exert a strong influence on French nationalism. Soon thereafter, the Dreyfus affair provided one of the political division lines of France. French nationalism, which had been largely associated with left-wing and Republican ideologies before the Dreyfus affair, turned after that into a main trait of the right-wing and, moreover, of the far right. A new right emerged, and nationalism was reappropriated by the far-right who turned it into a form of ethnic nationalism, blended with anti-Semitism, xenophobia, anti-Protestantism and anti-Masonry. The Action française (AF), first founded as a journal and later a political organization, was the matrix of a new type of counter-revolutionary right-wing, which continues to exist today. During the interwar period, the Action française and its youth militia, the Camelots du Roi, were very active. Far right leagues organized riots.

Nouvelle Résistance (NR) was a French far-right group created in August 1991 by Christian Bouchet as an offshoot of Troisième Voie, which was headed by Bouchet. Dissolved in 1997, NR described themselves as "national revolutionary" and part of the National Bolshevism international movement. It succeeded to the Troisième voie and Jeune Europe, a movement created in the 1960s by Jean-François Thiriart.

The Republican Federation was the largest conservative party during the French Third Republic, gathering together the progressive Orléanists rallied to the Republic.

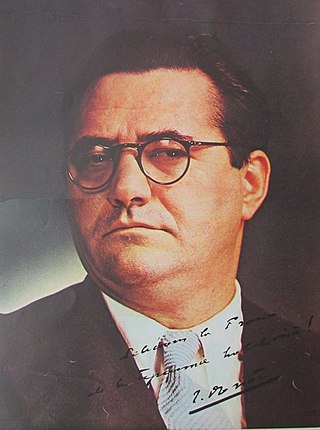

The Socialist Republican Union was a political party in France founded in 1935 during the late Third Republic which united the right-wing of the French Section of the Workers' International with the left-wing of the Radical republican movement.

The Independent Left was a French parliamentary group in the Chamber of Deputies of France of the French Third Republic during the interwar period. It was not a political party but a technical group formed by independents and parties too small to form their own parliamentary group, including dissidents from the Communist, Socialist and Radical-Socialist parties, as well as left-wing regional parties and left-wing Catholics.

Georges Izard was a French politician, lawyer, journalist and essayist.

Robert Soucy is an American historian, specializing in French fascist movements between 1924 and 1939, French fascist intellectuals Maurice Barrès and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, European fascism, twentieth-century European intellectual history, and Marcel Proust's aesthetics of reading.

The French Left refers to communist, socialist, social democratic, democratic socialist, and anarchist political forces in France. The term originates from the National Assembly of 1789, where supporters of the revolution were seated on the left of the assembly. During the 1800s, left largely meant support for the Republic, whereas right largely meant support for the monarchy.

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault". More generally, it is "a coalition especially of leftist political parties against a common opponent". However, other alliances such as the Popular Front of India have used the term, and not all leftist or anti-fascist coalitions use the term "popular front".

References

- ↑ "Le Populaire". 15 July 1935.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)