Summary

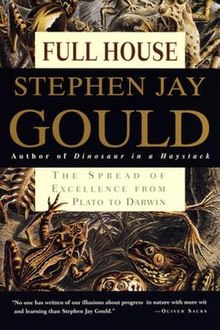

Full House aims to explain to the general reader how misconceptions about statistics can lead people to misunderstand the role variation plays in driving trends in complex systems. One misconception people often have is focusing too narrowly on averages or extreme values rather than the full spectrum of variation in the entire system (what Gould calls the "full house" of variation).

The book focuses on two main examples of this misconception: the disappearance of the 0.400 batting average in baseball, and the perceived tendency of evolution towards "progress" making organisms more complex and sophisticated.

In the first example, Gould explains that the decline of the top batting average does not imply that there has been a decline in the skill of baseball players. Quite the contrary: he shows that all that has happened is that the variance of the batting average decreased as professional baseball got better and better, while the league average remained constant as the game rules changed—together causing the extreme value of the distribution—the best batting average—to decrease as well.

In the second example, Gould points out that many people wrongly believe that the process of evolution has a preferred direction—a tendency to make organisms more complex and more sophisticated as time goes by. Those who believe in evolution's drive towards progress often demonstrate it with a series of organisms that appeared in different eons, with increasing complexity, e.g., "bacteria, fern, dinosaurs, dog, man". Gould explains how these increasingly complex organisms are just one end of the complexity distribution, and why looking only at them misses the entire picture—the "full house". He explains that by any measure, the most common organisms have always been, and still are, the bacteria. The complexity distribution is bounded at one side (a living organism cannot be much simpler than bacteria), so an unbiased random walk by evolution, sometimes going in the complexity direction and sometimes going towards simplicity (without having an intrinsic preference to either), will create a distribution with a small, but longer and longer tail at the high complexity end.

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certain characteristics becoming more or less common within a population over successive generations. The process of evolution has given rise to biodiversity at every level of biological organisation.

Stephen Jay Gould was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In 1996, Gould was hired as the Vincent Astor Visiting Research Professor of Biology at New York University, after which he divided his time teaching between there and Harvard.

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of human societies, sociobiology is closely allied to evolutionary anthropology, human behavioral ecology, evolutionary psychology, and sociology.

Richard Charles Lewontin was an American evolutionary biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and social commentator. A leader in developing the mathematical basis of population genetics and evolutionary theory, he applied techniques from molecular biology, such as gel electrophoresis, to questions of genetic variation and evolution.

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, the phrase is best understood as "survival of the form that in successive generations will leave most copies of itself."

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some goal (teleology) due to some internal mechanism or "driving force". According to the theory, the largest-scale trends in evolution have an absolute goal such as increasing biological complexity. Prominent historical figures who have championed some form of evolutionary progress include Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Henri Bergson.

Adaptationism is a scientific perspective on evolution that focuses on accounting for the products of evolution as collections of adaptive traits, each a product of natural selection with some adaptive rationale or raison d'etre.

The gene-centered view of evolution, gene's eye view, gene selection theory, or selfish gene theory holds that adaptive evolution occurs through the differential survival of competing genes, increasing the allele frequency of those alleles whose phenotypic trait effects successfully promote their own propagation. The proponents of this viewpoint argue that, since heritable information is passed from generation to generation almost exclusively by DNA, natural selection and evolution are best considered from the perspective of genes.

In biology, saltation is a sudden and large mutational change from one generation to the next, potentially causing single-step speciation. This was historically offered as an alternative to Darwinism. Some forms of mutationism were effectively saltationist, implying large discontinuous jumps.

The history of life on Earth seems to show a clear trend; for example, it seems intuitive that there is a trend towards increasing complexity in living organisms. More recently evolved organisms, such as mammals, appear to be much more complex than organisms, such as bacteria, which have existed for a much longer period of time. However, there are theoretical and empirical problems with this claim. From a theoretical perspective, it appears that there is no reason to expect evolution to result in any largest-scale trends, although small-scale trends, limited in time and space, are expected. From an empirical perspective, it is difficult to measure complexity and, when it has been measured, the evidence does not support a largest-scale trend.

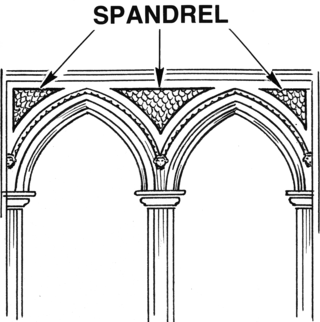

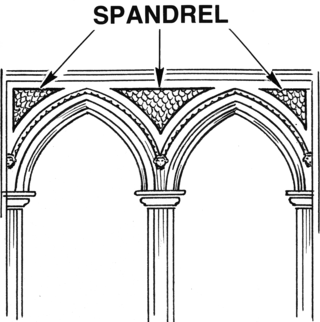

In evolutionary biology, a spandrel is a phenotypic trait that is a byproduct of the evolution of some other characteristic, rather than a direct product of adaptive selection. Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin brought the term into biology in their 1979 paper "The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme". Adaptationism is a point of view that sees most organismal traits as adaptive products of natural selection. Gould and Lewontin sought to temper what they saw as adaptationist bias by promoting a more structuralist view of evolution.

Many scientists and philosophers of science have described evolution as fact and theory, a phrase which was used as the title of an article by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould in 1981. He describes fact in science as meaning data, not known with absolute certainty but "confirmed to such a degree that it would be perverse to withhold provisional assent". A scientific theory is a well-substantiated explanation of such facts. The facts of evolution come from observational evidence of current processes, from imperfections in organisms recording historical common descent, and from transitions in the fossil record. Theories of evolution provide a provisional explanation for these facts.

The evolution of biological complexity is one important outcome of the process of evolution. Evolution has produced some remarkably complex organisms – although the actual level of complexity is very hard to define or measure accurately in biology, with properties such as gene content, the number of cell types or morphology all proposed as possible metrics.

Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design is a 2006 book by Michael Shermer, an author, publisher, and historian of science. Shermer examines the theory of evolution and the arguments presented against it. He demonstrates that the theory is very robust and is based on a convergence of evidence from a number of different branches of science. The attacks against it are, for the most part, very simplistic and easily demolished. He discusses how evolution and other branches of science can coexist with religious beliefs. He describes how he and Darwin both started out as creationists and how their thinking changed over time. He examines current attitudes towards evolution and science in general. He finds that in many cases the problem people have is not with the facts about evolution but with their ideas of what it implies.

Dawkins vs. Gould: Survival of the Fittest is a book about the differing views of biologists Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould by philosopher of biology Kim Sterelny. When published in 2001 it became an international best-seller. A new edition was published in 2007 to include Gould's The Structure of Evolutionary Theory finished shortly before his death in 2002, and recent works by Dawkins. The synopsis below is from the 2007 publication.

In biology, evolution is the process of change in all forms of life over generations, and evolutionary biology is the study of how evolution occurs. Biological populations evolve through genetic changes that correspond to changes in the organisms' observable traits. Genetic changes include mutations, which are caused by damage or replication errors in organisms' DNA. As the genetic variation of a population drifts randomly over generations, natural selection gradually leads traits to become more or less common based on the relative reproductive success of organisms with those traits.

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Church Fathers as well as in medieval Islamic science. With the beginnings of modern biological taxonomy in the late 17th century, two opposed ideas influenced Western biological thinking: essentialism, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept which had developed from medieval Aristotelian metaphysics, and that fit well with natural theology; and the development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to modern science: as the Enlightenment progressed, evolutionary cosmology and the mechanical philosophy spread from the physical sciences to natural history. Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence of palaeontology with the concept of extinction further undermined static views of nature. In the early 19th century prior to Darwinism, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) proposed his theory of the transmutation of species, the first fully formed theory of evolution.

In evolutionary biology, contingency describes how the outcome of evolution may be affected by the history of a particular lineage.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to evolution:

The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) consists of a set of theoretical concepts argued to be more comprehensive than the earlier modern synthesis of evolutionary biology that took place between 1918 and 1942. The extended evolutionary synthesis was called for in the 1950s by C. H. Waddington, argued for on the basis of punctuated equilibrium by Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge in the 1980s, and was reconceptualized in 2007 by Massimo Pigliucci and Gerd B. Müller.