Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic theologian who was dismissed from the University of Oxford in 1381 for heresy. The Lollards' demands were primarily for reform of Western Christianity. They formulated their beliefs in the Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards.

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. Puritanism played a significant role in English and early American history, especially during the Protectorate.

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation, was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Towards the end of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism and in turn resulted in a major schism within Western Christianity.

Peter Martyr Vermigli was an Italian-born Reformed theologian. His early work as a reformer in Catholic Italy and his decision to flee for Protestant northern Europe influenced many other Italians to convert and flee as well. In England, he influenced the Edwardian Reformation, including the Eucharistic service of the 1552 Book of Common Prayer. He was considered an authority on the Eucharist among the Reformed churches, and engaged in controversies on the subject by writing treatises. Vermigli's Loci Communes, a compilation of excerpts from his biblical commentaries organised by the topics of systematic theology, became a standard Reformed theological textbook.

John Owen was an English Puritan Nonconformist church leader, theologian, and vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford. One of the most prominent theologians in England during his lifetime, Owen was a prolific author who wrote articles, treatises, Biblical commentaries, poetry, children's catechisms, and other works. Many of Owen's works reflect his Calvinist interpretation of Scripture. Owen is still widely read by Calvinists today, and is known particularly for his writings on sin and human depravity.

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. Elements of the sermon often include exposition, exhortation, and practical application. The act of delivering a sermon is called preaching. In secular usage, the word sermon may refer, often disparagingly, to a lecture on morals.

William Perkins (1558–1602) was an influential English cleric and Cambridge theologian, receiving a B.A. and M.A. from the university in 1581 and 1584 respectively, and also one of the foremost leaders of the Puritan movement in the Church of England during the Elizabethan era. Although not entirely accepting of the Church of England's ecclesiastical practices, Perkins conformed to many of the policies and procedures imposed by the Elizabethan Settlement. He did remain, however, sympathetic to the non-conformist puritans and even faced disciplinary action for his support.

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Reformation. It permanently shaped the Church of England's doctrine and liturgy, laying the foundation for the unique identity of Anglicanism.

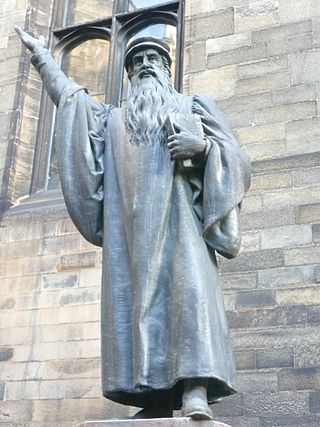

The pulpit gown, also called pulpit robe or preaching robe, is a black gown worn by Christian ministers for preaching. It is particularly associated with Reformed churches, while also used in the Anglican, Methodist, Lutheran and Unitarian traditions.

Protestantism originated from the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. The term Protestant comes from the Protestation at Speyer in 1529, where the nobility protested against enforcement of the Edict of Worms which subjected advocates of Lutheranism to forfeit all of their property. However, the theological underpinnings go back much further, as Protestant theologians of the time cited both Church Fathers and the Apostles to justify their choices and formulations. The earliest origin of Protestantism is controversial; with some Protestants today claiming origin back to people in the early church deemed heretical such as Jovinian and Vigilantius.

Matthias Faber, S.J., was a German Jesuit priest, who gained fame as a religious writer and preacher.

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Paul's Cross was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit in St Paul's Churchyard, the grounds of Old St Paul's Cathedral, City of London. It was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England, and many of the most important statements on the political and religious changes brought by the Reformation were made public from here. The pulpit stood in 'the Cross yard', the open space on the north-east side of St Paul's Churchyard, adjacent to the row of buildings that would become the home of London's publishing and book-selling trade.

Patrick "Pat" Collinson, was an English historian, known as a writer on the Elizabethan era, particularly Elizabethan Puritanism. He was emeritus Regius Professor of Modern History, University of Cambridge, having occupied the chair from 1988 to 1996. He once described himself as "an early modernist with a prime interest in the history of England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries."

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes justification of sinners through faith alone, the teaching that salvation comes by unmerited divine grace, the priesthood of all believers, and the Bible as the sole infallible source of authority for Christian faith and practice. The five solae summarize the basic theological beliefs of mainstream Protestantism.

The reign of Elizabeth I of England, from 1558 to 1603, saw the start of the Puritan movement in England, its clash with the authorities of the Church of England, and its temporarily effective suppression as a political movement in the 1590s by judicial means. This led to the further alienation of Anglicans and Puritans from one another in the 17th century during the reigns of King James and King Charles I, that eventually brought about the English Civil War, the brief rule of the Puritan Lord Protector of England Oliver Cromwell, the English Commonwealth, and as a result the political, religious, and civil liberty that is celebrated today in all English speaking countries.

The Westminster Conference of 1559 was a religious disputation held early in the reign of Elizabeth I of England. Although the proceedings themselves were perfunctory, the outcome shaped the Elizabethan religious settlement and resulted in the authorisation of the 1559 Book of Common Prayer.

Historians have produced and worked with a number of definitions of Puritanism, in an unresolved debate on the nature of the Puritan movement of the 16th and 17th century. There are some historians who are prepared to reject the term for historical use. John Spurr argues that changes in the terms of membership of the Church of England, in 1604–6, 1626, 1662, and also 1689, led to re-definitions of the word "Puritan". Basil Hall, citing Richard Baxter considers that "Puritan" dropped out of contemporary usage in 1642, with the outbreak of the First English Civil War, being replaced by more accurate religious terminology. Current literature on Puritanism supports two general points: Puritans were identifiable in terms of their general culture, by contemporaries, which changed over time; and they were not identified by theological views alone.

The Bohemian Reformation, preceding the Reformation of the 16th century, was a Christian movement in the late medieval and early modern Kingdom and Crown of Bohemia striving for a reform of the Catholic Church. Lasting for more than 200 years, it had a significant impact on the historical development of Central Europe and is considered one of the most important religious, social, intellectual and political movements of the early modern period. The Bohemian Reformation produced the first national church separate from Roman authority in the history of Western Christianity, the first apocalyptic religious movement of the early modern period, and the first pacifist Protestant church.

Protestant liturgy or Evangelical liturgy is a pattern for worship used by a Protestant congregation or denomination on a regular basis. The term liturgy comes from Greek and means "public work". Liturgy is especially important in the Historical Protestant churches, both mainline and evangelical, while Baptist, Pentecostal, and nondenominational churches tend to be very flexible and in some cases have no liturgy at all. It often but not exclusively occurs on Sunday.