The Celts or Celtic peoples were a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia, identified by their use of Celtic languages and other cultural similarities. Major Celtic groups included the Gauls; the Celtiberians and Gallaeci of Iberia; the Britons, Picts, and Gaels of Britain and Ireland; the Boii; and the Galatians. The relation between ethnicity, language and culture in the Celtic world is unclear and debated; for example over the ways in which the Iron Age people of Britain and Ireland should be called Celts. In current scholarship, 'Celt' primarily refers to 'speakers of Celtic languages' rather than to a single ethnic group.

Gaul was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of 494,000 2 (191,000 sq mi). According to Julius Caesar, who took control of the region on behalf of the Roman Republic, Gaul was divided into three parts: Gallia Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania.

The Eburones were a Gaulish-Germanic tribe dwelling in the northeast of Gaul, who lived north of the Ardennes in the region near that is now the southern Netherlands, eastern Belgium and the German Rhineland, in the period immediately preceding the Roman conquest of the region. Though living in Gaul, they were also described as being both Belgae and Germani.

Pan-Celticism, also known as Celticism or Celtic nationalism is a political, social and cultural movement advocating solidarity and cooperation between Celtic nations and the modern Celts in Northwestern Europe. Some pan-Celtic organisations advocate the Celtic nations seceding from the United Kingdom and France and forming their own separate federal state together, while others simply advocate very close cooperation between independent sovereign Celtic nations, in the form of Breton, Cornish, Irish, Manx, Scottish, and Welsh nationalism.

Roman Gaul refers to Gaul under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century BC to the 5th century AD.

The Continental Celtic languages are the now-extinct group of the Celtic languages that were spoken on the continent of Europe and in central Anatolia, as distinguished from the Insular Celtic languages of the British Isles and Brittany. Continental Celtic is a geographic, rather than linguistic, grouping of the ancient Celtic languages.

Gallo-Roman religion is a fusion of the traditional religious practices of the Gauls, who were originally Celtic speakers, and the Roman and Hellenistic religions introduced to the region under Roman Imperial rule. It was the result of selective acculturation.

The name France comes from Latin Francia.

Romanization or Latinization, in the historical and cultural meanings of both terms, indicate different historical processes, such as acculturation, integration and assimilation of newly incorporated and peripheral populations by the Roman Republic and the later Roman Empire. The terms were used in ancient Roman historiography and traditional Italian historiography until the Fascist period, when the various processes were called the "civilizing of barbarians".

Ethnopluralism or ethno-pluralism, also known as ethno-differentialism, is a far-right political model which attempts to preserve separate and bordered ethno-cultural regions. According to its promoters, significant foreign cultural elements in a given region ought to be culturally assimilated to seek cultural homogenization in this territory, in order to let different cultures thrive in their respective geographical areas. Advocates also emphasize a "right to difference" and claim support for cultural diversity at a worldwide rather than at a national level.

Alise-Sainte-Reine is a commune in the Côte-d'Or department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region of eastern France.

Post-colonial anarchism is a term used to describe anarchism in an anti-imperialist framework. Whereas traditional anarchism arose from industrialized Western nations—and thus sees history from their perspective—post-colonial anarchism approaches the same principles of anarchism from the perspective of colonized peoples. It is highly critical of the contributions of the established anarchist movement, and seeks to add what it sees as a unique and important perspective. The tendency is strongly influenced by indigenism, anti-state forms of nationalism, and anarchism among ethnic minorities, among other sources.

The various names used since classical times for the people known today as the Celts are of disparate origins.

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context. The well-studied meld of cultures in Gaul gives historians a model against which to compare and contrast parallel developments of Romanization in other less-studied Roman provinces.

The Gauls were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period. Their homeland was known as Gaul (Gallia). They spoke Gaulish, a continental Celtic language.

The Gallo-Brittonic languages, also known as the P-Celtic languages, are a proposed subdivision of the Celtic languages containing the languages of Ancient Gaul and Celtic Britain, which share certain features. Besides common linguistic innovations, speakers of these languages shared cultural features and history. The cultural aspects are commonality of art styles and worship of similar gods. Coinage just prior to the British Roman period was also similar. In Julius Caesar's time, the Atrebates held land on both sides of the English Channel.

Gaius Valerius Troucillus or Procillus was a Helvian Celt who served as an interpreter and envoy for Julius Caesar in the first year of the Gallic Wars. Troucillus was a second-generation Roman citizen, and is one of the few ethnic Celts who can be identified both as a citizen and by affiliation with a Celtic polity. His father, Caburus, and a brother are named in Book 7 of Caesar's Bellum Gallicum as defenders of Helvian territory against a force sent by Vercingetorix in 52 BC. Troucillus plays a role in two episodes from the first book of Caesar's war commentaries, as an interpreter for the druid Diviciacus and as an envoy to the Suebian king Ariovistus, who accuses him of spying and has him thrown in chains.

The Helvii were a relatively small Celtic polity west of the Rhône river on the northern border of Gallia Narbonensis. Their territory was roughly equivalent to the Vivarais, in the modern French department of Ardèche. Alba Helviorum was their capital, possibly the Alba Augusta mentioned by Ptolemy, and usually identified with modern-day Alba-la-Romaine. In the 5th century the capital seems to have been moved to Viviers.

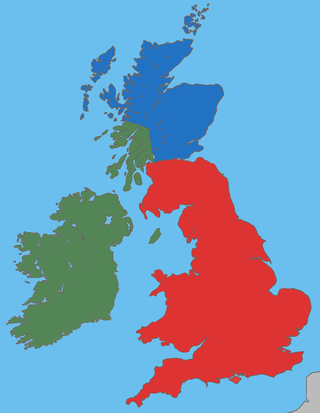

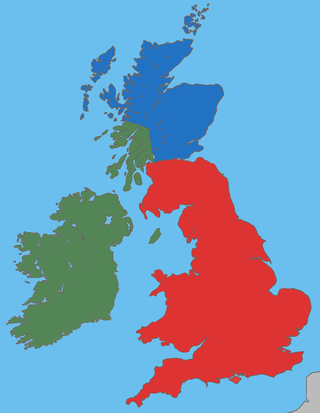

The Insular Celts were speakers of the Insular Celtic languages in the British Isles and Brittany. The term is mostly used for the Celtic peoples of the isles up until the early Middle Ages, covering the British–Irish Iron Age, Roman Britain and Sub-Roman Britain. They included the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels.

Gaulish is an extinct Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul. In a wider sense, it also comprises varieties of Celtic that were spoken across much of central Europe ("Noric"), parts of the Balkans, and Anatolia ("Galatian"), which are thought to have been closely related. The more divergent Lepontic of Northern Italy has also sometimes been subsumed under Gaulish.