The Swedish Social Democratic Party, formally the SwedishSocial Democratic Workers' Party, usually referred to as The Social Democrats, is a centre-left social democratic and democratic socialist political party in Sweden. Globally, it is a full member of the Progressive Alliance and the Party of European Socialists.

The welfare state of the United Kingdom began to evolve in the 1900s and early 1910s, and comprises expenditures by the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland intended to improve health, education, employment and social security. The British system has been classified as a liberal welfare state system.

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for citizens unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life.

Economic inequality is an umbrella term for a) income inequality or distribution of income, b) wealth inequality or distribution of wealth, and c) consumption inequality. Each of these can be measured between two or more nations, within a single nation, or between and within sub-populations.

In political economy, decommodification is the strength of social entitlements and citizens' degree of immunization from market dependency.

Gøsta Esping-Andersen is a Danish sociologist whose primary focus has been on the welfare state and its place in capitalist economies. Jacob Hacker describes him as the "dean of welfare state scholars." Over the past decade his research has moved towards family demographic issues. A synthesis of his work was published as Families in the 21st Century.

Workfare is a governmental plan under which welfare recipients are required to accept public-service jobs or to participate in job training. Many countries around the world have adopted workfare to reduce poverty among able-bodied adults; however, their approaches to execution vary. The United States and United Kingdom are two countries utilizing workfare, albeit with different backgrounds.

Social welfare, assistance for the ill or otherwise disabled and the old, has long been provided in Japan by both the government and private companies. Beginning in the 1920s, the Japanese government enacted a series of welfare programs, based mainly on European models, to provide medical care and financial support. During the post-war period, a comprehensive system of social security was gradually established. Universal health insurance and a pension system were established in 1960.

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) are government programmes that intervene in the labour market to help the unemployed find work, but also for the underemployed and employees looking for better jobs. In contrast, passive labour market policies involve expenditures on unemployment benefits and early retirement. Historically, labour market policies have developed in response to both market failures and socially/politically unacceptable outcomes within the labor market. Labour market issues include, for instance, the imbalance between labour supply and demand, inadequate income support, shortages of skilled workers, or discrimination against disadvantaged workers.

In Italy, unemployment benefits are guaranteed by the Constitution. Article 38 states "[...] workers have the right to the provision of financial support sufficient to meet their needs in case of accidents at work, ill health, disability, old age and involuntary unemployment [...]". Esping-Andersen traces in this persistency the origins of the chronically high Italian unemployment rates.

The Nordic model comprises the economic and social policies as well as typical cultural practices common in the Nordic countries. This includes a comprehensive welfare state and multi-level collective bargaining based on the economic foundations of social corporatism, and a commitment to private ownership within a market-based mixed economy – with Norway being a partial exception due to a large number of state-owned enterprises and state ownership in publicly listed firms.

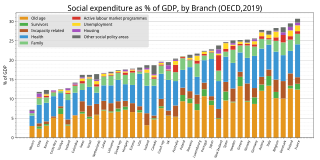

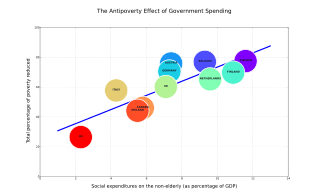

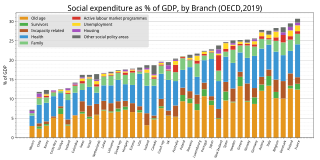

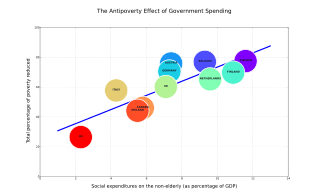

The effects of social welfare on poverty have been the subject of various studies.

The modern welfare state has been criticized on economic and moral grounds from all ends of the political spectrum. Many have argued that the provision of tax-funded services or transfer payments reduces the incentive for workers to seek employment, thereby reducing the need to work, reducing the rewards of work and exacerbating poverty. On the other hand, socialists typically criticize the welfare state as championed by social democrats as an attempt to legitimize and strengthen the capitalist economic system which conflicts with the socialist goal of replacing capitalism with a socialist economic system.

The breadwinner model is a paradigm of family centered on a breadwinner, "the member of a family who earns the money to support the others." Traditionally, the earner works outside the home to provide the family with income and benefits such as health insurance, while the non-earner stays at home and takes care of children and the elderly. The breadwinner model largely arose in western cultures after industrialization occurred. Before industrialization, all members of the household—including men, women, and children—contributed to the productivity of the household. Gender roles underwent a re-definition as a result of industrialization, with a split between public and private roles for men and women, which did not exist before industrialization.

The gender pay gap or gender wage gap is the average difference between the remuneration for men and women who are working. Women are generally found to be paid less than men. There are two distinct numbers regarding the pay gap: non-adjusted versus adjusted pay gap. The latter typically takes into account differences in hours worked, occupations chosen, education and job experience. In other words, the adjusted values represent how much women and men make for the same work, while the non-adjusted values represent how much the average man and woman make in total. In the United States, for example, the non-adjusted average woman's annual salary is 79–83% of the average man's salary, compared to 95–99% for the adjusted average salary.

The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism is a book on political theory written by Danish sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen, published in 1990. The work is Esping-Andersen's most influential and highly cited work, outlining three main types of welfare states, in which modern developed capitalist nations cluster. The work occupies seminal status in the comparative analysis of the welfare states of Western Europe and other advanced capitalist economies.

Denmark has been noted as having one of the lowest income inequality ratings in the world and has been known to maintain relative stability in this metric throughout decades past. The OECD data of 2016 gives Denmark a Gini coefficient of 0.249, below the OECD average of 0.315. The OECD in 2013 ranked Denmark with having a 0.254 Gini coefficient, ranking third behind Iceland and Norway respectively as the countries with the lowest income inequality qualifications. Eurostat ranked Denmark with a Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income of 27.0 in 2022, having fallen for three straight years from a high of 27.8 in 2018. The Gini coefficients are measured using a 0–1 calibration where 0 equals complete equality and 1 equals complete inequality. "Wage-distributive outcomes" and their effect on income equality have been noted since the 1970s and 80s. Denmark, along with other Nordic countries, such as Finland and Sweden, has long held a stable low wage inequality index as well.

Welfare in Peru began on a base of democratic views. Its political system is a multi-party system that includes having a President and Prime Minister. The economy of Peru has expanded substantially throughout the years making it one of the fastest growing economies. As described by Gøsta Esping-Andersen, in his book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, the Peruvian welfare system would most commonly fit in with the liberal model, since Peru mostly attempts to emancipate the less fortunate from poverty, through means of state-cultivated programs. In accordance, the welfare system has shown great expansion, with the focus primarily on education, healthcare, and the creation of a social safety net.

Even in the modern era, gender inequality remains an issue in Japan. In 2015, the country had a per-capita income of US$38,883, ranking 22nd of the 188 countries, and No. 18 in the Human Development Index. In the 2019 Gender Inequality Index report, it was ranked 17th out of the participating 162 countries, ahead of Germany, the UK and the US, performing especially well on the reproductive health and higher education attainment indices. Despite this, gender inequality still exists in Japan due to the persistence of gender norms in Japanese society rooted in traditional religious values and government reforms. Gender-based inequality manifests in various aspects from the family, or ie, to political representation, to education, playing particular roles in employment opportunities and income, and occurs largely as a result of defined roles in traditional and modern Japanese society. Inequality also lies within divorce of heterosexual couples and the marriage of same sex couples due to both a lack of protective divorce laws and the presence of restrictive marriage laws. In consequence to these traditional gender roles, self-rated health surveys show variances in reported poor health, population decline, reinforced gendered education and social expectations, and inequalities in the LGBTQ+ community.

A property-owning democracy is a social system whereby state institutions enable a fair distribution of productive property across the populace generally, rather than allowing monopolies to form and dominate. This intends to ensure that all individuals have a fair and equal opportunity to participate in the market. It is thought that this system is necessary to break the constraints of welfare-state capitalism and manifest a cooperation of citizens, who each hold equal political power and potential for economic advancement. This form of societal organisation was popularised by John Rawls, as the most effective structure amongst four other competing systems: laissez-faire capitalism, welfare-state capitalism, state socialism with a command economy and liberal socialism. The idea of a property-owning democracy is somewhat foreign in Western political philosophy, despite issues of political disenfranchisement emerging concurrent to the accelerating inequality of wealth and capital ownership over the past four decades.