Related Research Articles

Giovanni Paisiello was an Italian composer of the Classical era, and was the most popular opera composer of the late 1700s. His operatic style influenced Mozart and Rossini.

Il Bellerofonte is an 18th-century Italian opera in three acts by the Czech composer Josef Mysliveček. It conforms to the serious type that was typically set in the distant past. The libretto, based on the Greek legend of Bellerophon, was written by Giuseppe Bonecchi. The work was dedicated to King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies and was first performed at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples on 20 January 1767, the birthday of his father, King Charles III of Spain. The cast featured two stellar singers of the time, Caterina Gabrielli and Anton Raaff, in the leading roles. The opera was only the composer's second one, and the first that permitted him the opportunity to write music for first-rate vocal artists. The production was highly successful, indeed responsible for a meteoric rise in his reputation as an operatic composer. From the time of the premiere of Bellerofonte until his death in 1781, Mysliveček succeeded in having more new opere serie brought into production than any other composer in Europe. During the same time span, he also had more new operas staged at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples than any other composer.

Ballet d'action is a hybrid genre of expressive and symbolic ballet that emerged during the 18th century. One of its chief aims was to liberate the conveyance of a story via spoken or sung words, relying simply on quality of movement to communicate actions, motives, and emotions. The expression of dancers was highlighted in many of the influential works as a vital aspect of the ballet d'action. To become an embodiment of emotion or passion through free expression, movement, and realistic choreography was one chief aim of this dance. Thus, the mimetic aspect of dance was used to convey what the lack of dialogue could not. Certainly, there may have been codified gestures; however, a main tenant of the ballet d'action was to free dance from unrealistic symbolism, so this remains an elusive question. Often, props and costume object were involved in the performance to help clarify character interaction and passions. An example would be the scarf from La Fille mal gardée, which represents the love of the male character and which the female character accepts after a coy moment. Props were thus used in harmony with dancer movement and expression. Programs for plays were also a place to explain the onstage action; however, overt clarifications were sometimes criticized for sullying the art of the ballet d'action.

Fabio Grossi is a retired Italian dancer and ballet teacher.

Gasparo Angiolini, real name Domenico Maria Gasparo, son of Francesco Angiolini and Maria Maddalena Torzi, was an Italian dancer, choreographer and composer. He was born in Florence and died in Milan.

Grotesque dance is a category of theatrical dance that became more clearly differentiated in the 18th century and was incorporated into ballet, although it had its roots in earlier centuries. As opposed to the danse noble or "noble dance" performed in royal courts which emphasized beauty of movement and noble themes, grotesque dances were comic or lighthearted and created for buffoons and commedia dell'arte characters to amuse and entertain spectators or patrons. In 16th and 17th centuries grotesque dances were often presented as an anti-masque, performed between the acts of more serious courtly entertainments. Likewise, the 17th century entrée de ballet sometimes contained grotesque sequences, most notably those devised by the Duke of Nemours for the court of Louis XIII.

Giuseppe Aprile was an Italian castrato singer and music teacher. He was also known as 'Sciroletto' or 'Scirolino'.

The La Scala Theatre Ballet is the resident classical ballet company at La Scala in Milan, Italy. One of the oldest and most renowned ballet companies in the world, the company pre-dates the theatre, but was officially founded at the inauguration of La Scala in 1778. Many leading dancers have performed with the company, including Mara Galeazzi, Alessandra Ferri, Viviana Durante, Roberto Bolle and Carla Fracci. The official associate school of the company is the La Scala Theatre Ballet School, a constituent of the La Scala Theatre Academy.

Caterina Gabrielli, born Caterina Fatta, was an Italian coloratura singer. She was the most important soprano of her age. A woman of great personal charm and dynamism, Charles Burney referred to her as "the most intelligent and best-bred virtuosa" that he had ever encountered. The excellence of her vocal artistry is reflected in the fact that she was able to secure long-term engagements in three of the most prestigious operatic centers in her day outside of Italy.

Jacopo Godani is an Italian dancer-choreographer who directs Dresden Frankfurt Dance Company

The Teatro San Benedetto was a theatre in Venice, particularly prominent in the operatic life of the city in the 18th and early 19th centuries. It saw the premieres of over 140 operas, including Rossini's L'italiana in Algeri, and was the theatre of choice for the presentation of opera seria until La Fenice was built in 1792.

Florian Johann Deller was an Austrian composer and violinist.

Gian Francesco de Majo was an Italian composer. He is best known for his more than 20 operas. He also composed a considerable amount of sacred works, including oratorios, cantatas, and masses.

Hippolyte Monplaisir was a French dancer, choreographer and ballet master.

Renato Zanella is an Italian-born ballet dancer, choreographer and director. He studied classical ballet for several years before becoming a choreographer for various professional companies. Due to his success, he has won many awards and honorary titles within the ballet community.

Vincenzo Galeotti was an Italian-born Danish dancer, choreographer and ballet master, who was influential as the director of the Royal Danish Ballet from 1775 until his death.

Rosina Galli was an Italian ballet dancer, choreographer, ballet mistress, and dance teacher. After early years in Italy, she moved to the US, where she was associated with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Prima ballerina at La Scala Theatre Ballet, and the Chicago Ballet, she was also the première danseuse at the Teatro di San Carlo and the Metropolitan Opera.

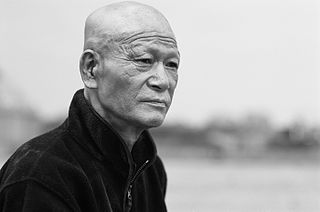

Kō Murobushi was a Japanese dancer and choreographer who was a leading inheritor of Tatsumi Hijikata's original vision of Butoh.

Lorca Massine is an American choreographer and dancer, born in New York on July 25, 1944, he was born by a Russian immigrant. He studied dance with his father, Victor Gsovsky, Asaf Messerer and Anatole Wilzac. Over his career, he has collaborated with world-acclaimed choreographers such as Balanchine, Béjart, and his father, Léonide Massine,.

In hermeneutics, Arianna Béatrice Fabbricatore has used the term entropy, relying on the works of Umberto Eco, to identify and assess the loss of meaning between the verbal description of dance and the choreotext generated by inter-semiotic translation operations.

References

- ↑ L’action dans le texte. Pour une approche herméneutique du Trattato teorico-prattico di ballo (1779) de G. Magri, [Ressource ARDP 2015], Pantin, CN D, 2018 (116 p.)https://hddanse.hypotheses.org/272

- 1 2 3 4 Bongiovanni, Salvatore. “Gennaro Magri, a Grotesque Dancer on the European Stage.” The Grotesque Dancer on the Eighteenth-Century Stage: Gennaro Magri and His World, by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Bruce Alan. Brown, University of Wisconsin Press, 2005, pp. 33–61, 91-108. ISBN 0299203549

- ↑ Brown, Bruce Alan. “Magri in Vienna, The Apprenticeship of a Choreographer.” The Grotesque Dancer on the Eighteenth-Century Stage: Gennaro Magri and His World, by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Bruce Alan. Brown, University of Wisconsin Press, 2005, pp. 61–90. ISBN 0299203549

- 1 2 Bongiovanni, Salvatore. “Magri in Naples: Defending the Italian Dance Tradition.” The Grotesque Dancer on the Eighteenth-Century Stage: Gennaro Magri and His World, by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Bruce Alan. Brown, University of Wisconsin Press, 2005, pp. 91-108. ISBN 0299203549

- ↑ Trattato teorico-prattico di ballo

- ↑ "Trattato teorico-prattico di ballo — Discours sur la danse".

- ↑ Arianna Béatrice Fabbricatore, « Semiotic elements of the grotesque “Italian” practice » in Tanz in Italien : italienischer Tanz in Europa 1400-1900 : 4. Symposion für Historischen Tanz, Burg Rothenfels am Main, 25.-29. Mai 2016 : Tagungsband, ed. Uwe W Schlottermüller; Howard Weiner; Marie Richter, Freiburg, Fa-gisis, Musik-und Tanzedition, 2016, p. 56-74.https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01552341/document

- ↑ Arianna Béatrice Fabbricatore, La danse comique et grotesque : interprétation cinétique du Trattato teorico-prattico di Ballo (1779) de Gennaro Magri. Synthèse du projet, Pantin, CN D, Aide à la recherche et au patrimoine en danse, 2015

- ↑ L’action dans le texte (in French)

- ↑ Tomko, Linda. "Magri's Grotteschi." The Grotesque Dancer on the Eighteenth-Century Stage: Gennaro Magri and His World, by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Bruce Alan. Brown, University of Wisconsin Press, 2005, pp. 109–149. ISBN 0299203549