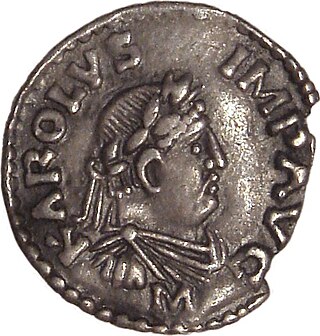

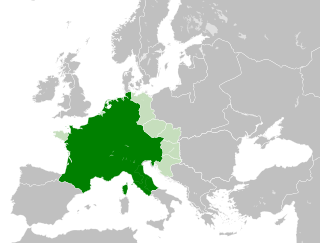

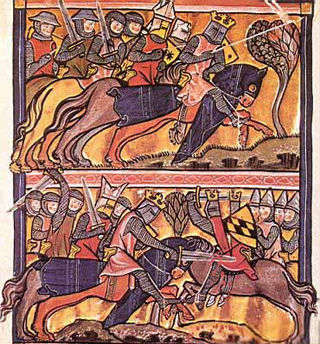

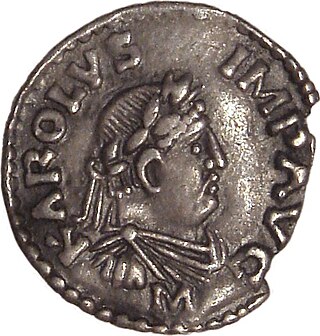

Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian Empire from 800, holding these titles until his death in 814. He united most of Western and Central Europe and was the first recognised emperor to rule in the west after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's reign was marked by political and social changes that had lasting impact on Europe throughout the Middle Ages.

Einhard was a Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the Vita Karoli Magni, "one of the most precious literary bequests of the early Middle Ages".

Louis the Pious, also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only surviving son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father's death in 814, a position that he held until his death except from November 833 to March 834, when he was deposed.

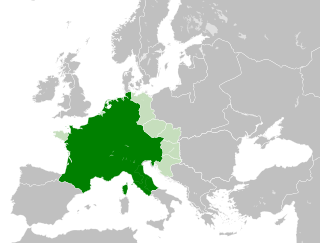

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the Roman Empire from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. The Carolingian Empire is sometimes considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

Carloman I, also Karlmann, Karlomann, was king of the Franks from 768 until he died in 771. He was the second surviving son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon and was a younger brother of Charlemagne. His death allowed Charlemagne to take all of Francia and begin his expansion into other kingdoms.

Abul-Abbas was an Asian elephant brought back to the Carolingian emperor Charlemagne by his diplomat Isaac the Jew. The gift was from the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid and symbolizes the beginning of Abbasid–Carolingian relations. The elephant's name and events from his life are recorded in the Carolingian Annales regni Francorum, and he is mentioned in Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni. However, no references to the gift or to interactions with Charlemagne have been found in Abbasid records.

Luitgard was the last wife of Charlemagne.

Notker the Stammerer, Notker Balbulus, or simply Notker, was a Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Saint Gall active as a composer, poet and scholar. Described as "a significant figure in the Western Church", Notker made substantial contributions to both the music and literature of his time. He is usually credited with two major works of the Carolingian period: the Liber Hymnorum, which includes an important collection of early musical sequences, and an early biography of Charlemagne, the Gesta Karoli Magni. His other works include a biography of Saint Gall known as the Vita Sancti Galli and a martyrology, among others.

Ermengardeof Hesbaye, probably a member of the Robertian dynasty, was Carolingian empress from 813 and Queen of the Franks from 814 until her death as the wife of the Carolingian emperor Louis the Pious.

The Royal Frankish Annals, also called the Annales Laurissenses maiores, are a series of annals composed in Latin in the Carolingian Francia, recording year-by-year the state of the monarchy from 741 to 829. Their authorship is unknown, though Wilhelm von Giesebrecht suggested that Arno of Salzburg was the author of an early section surviving in the copy at Lorsch Abbey. The Annals are believed to have been composed in successive sections by different authors, and then compiled.

Drogo, also known as Dreux or Drogon, was an illegitimate son of Frankish emperor Charlemagne by the concubine Regina.

Lewis Guy Melville Thorpe FRSA FRHistS was a British philologist and translator. He was married to the Italian scholar and lexicographer Barbara Reynolds.

Saint Clement of Ireland (Clemens Scotus) (c. 750 – 818) is venerated as a saint by the Catholic Church.

Rorgon I or Rorico(n) I was the first Count of Maine and progenitor of the Rorgonid dynasty, which is named for him. He was Count of Rennes from 819 and of Maine from 832 until his death.

Pepin, or Pippin the Hunchback was a Frankish prince. He was the eldest son of Charlemagne and noblewoman Himiltrude. He developed a humped back after birth, leading early medieval historians to give him the epithet "hunchback". He lived with his father's court after Charlemagne dismissed his mother and took another wife, Hildegard. Around 781, Pepin's half brother Carloman was rechristened as "Pepin of Italy"—a step that may have signaled Charlemagne's decision to disinherit the elder Pepin, for a variety of possible reasons. In 792, Pepin the Hunchback revolted against his father with a group of leading Frankish nobles, but the plot was discovered and put down before the conspiracy could put it into action. Charlemagne commuted Pepin's death sentence, having him tonsured and exiled to the monastery of Prüm instead. Since his death in 811, Pepin has been the subject of numerous works of historical fiction.

Gerberga was the wife of Carloman I, King of the Franks, and sister-in-law of Charlemagne. Her flight to the Lombard kingdom of Desiderius following Carloman's death precipitated the last Franco-Lombard war, and the end of the independent kingdom of the Lombards in 774.

Wala was a son of Bernard, son of Charles Martel, and one of the principal advisers of his cousin Charlemagne, of Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious, and of Louis's son Lothair I. He succeeded his brother Adalard as abbot of Corbie and its new daughter foundation, Corvey, in 826 or 827. His feast day is 31 August

Vita Karoli Magni is a biography of Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Emperor of the Romans, written by Einhard. The Life of Charlemagne is a 33 chapter account starting with the full genealogy of the Merovingian family, going through the rise of the Carolingian dynasty, and then detailing the exploits and temperament of King Charles. It has long been seen as one of the key sources for the reign of Charlemagne and provides insight into the court of King Charles and the events that surrounded him.

The Karolus magnus et Leo papa, sometimes called the Paderborn Epic or the Aachen Epic, is a Carolingian Latin epic poem of which only the third of four books is extant. It recounts the meeting of Charlemagne, king of the Franks, with Pope Leo III, in AD 799.

Autchar was a Frankish nobleman. He served Pippin III as a diplomat in 753 and followed Carloman I after the division of the kingdom in 768. In 772, refusing to accept Carloman's brother Charlemagne as king, he went into exile in the Lombard kingdom with Carloman's widow and sons. He was captured when Charlemagne invaded the kingdom in 773. His role in the fall of the Lombard kingdom was the subject of legendary embellishment a century later and in the chansons de geste he evolved into the figure of Ogier the Dane.