Related Research Articles

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror, is a loose literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name refers to Gothic architecture of the European Middle Ages, which was characteristic of the settings of early Gothic novels.

Horror is a genre of fiction that is intended to disturb, frighten or scare. Horror is often divided into the sub-genres of psychological horror and supernatural horror, which are in the realm of speculative fiction. Literary historian J. A. Cuddon, in 1984, defined the horror story as "a piece of fiction in prose of variable length ... which shocks, or even frightens the reader, or perhaps induces a feeling of repulsion or loathing". Horror intends to create an eerie and frightening atmosphere for the reader. Often the central menace of a work of horror fiction can be interpreted as a metaphor for larger fears of a society.

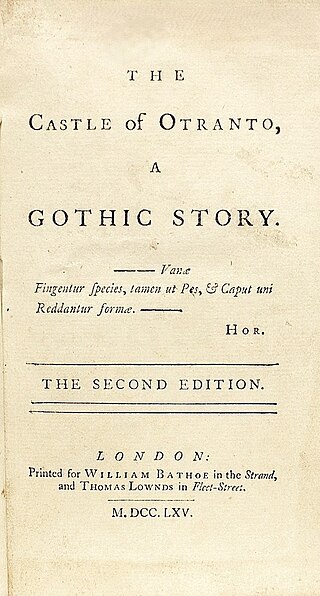

The Castle of Otranto is a novel by Horace Walpole. First published in 1764, it is generally regarded as the first gothic novel. In the second edition, Walpole applied the word 'Gothic' to the novel in the subtitle – A Gothic Story. Set in a haunted castle, the novel merged medievalism and terror in a style that has endured ever since. The aesthetic of the book has shaped modern-day gothic books, films, art, music, and the goth subculture.

Penny dreadfuls were cheap popular serial literature produced during the 19th century in the United Kingdom. The pejorative term is roughly interchangeable with penny horrible, penny awful, and penny blood. The term typically referred to a story published in weekly parts of 8 to 16 pages, each costing one penny. The subject matter of these stories was typically sensational, focusing on the exploits of detectives, criminals, or supernatural entities. First published in the 1830s, penny dreadfuls featured characters such as Sweeney Todd, Dick Turpin, Varney the Vampire, and Spring-heeled Jack.

A chapbook is a type of small printed booklet that was popular medium for street literature throughout early modern Europe. Chapbooks were usually produced cheaply, illustrated with crude woodcuts and printed on a single sheet folded into 8, 12, 16, or 24 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch. Printers provided chapbooks on credit to chapmen, who sold them both from door to door and at markets and fairs, then paying for the stock they sold. The tradition of chapbooks emerged during the 16th century as printed books were becoming affordable, with the medium ultimately reaching its height of popularity during the 17th and 18th centuries. Different ephemera and popular or folk literature were published as chapbooks, such as almanacs, children's literature, folklore, ballads, nursery rhymes, pamphlets, poetry, and political and religious tracts. The term chapbook remains in use by publishers to refer to short, inexpensive booklets.

"The Outsider" is a short story by American horror writer H. P. Lovecraft. Written between March and August 1921, it was first published in Weird Tales, April 1926. In this work, a mysterious individual who has been living alone in a castle for as long as he can remember decides to break free in search of human contact and light. "The Outsider" is one of Lovecraft's most commonly reprinted works and is also one of the most popular stories ever to be published in Weird Tales.

The three-volume novel was a standard form of publishing for British fiction during the nineteenth century. It was a significant stage in the development of the modern novel as a form of popular literature in Western culture.

Mary Elizabeth Mann, née Rackham, was a celebrated English novelist in the 1890s and early 1900s. She also wrote short stories, primarily on themes of poverty and rural English life. As an author she was commonly known as Mary E. Mann.

Jane Loudon, also known as Jane C. Loudon, or Mrs. Loudon in her publications, was an English writer and early pioneer of science fiction. She wrote before the term was coined, and was discussed for a century as a writer of Gothic fiction, fantasy or horror. She also created the first popular gardening manuals, as opposed to specialist horticultural works, reframing the art of gardening as fit for young women. She was married to the well-known horticulturalist John Claudius Loudon, and they wrote some books together, as well as her own very successful series.

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is an 1818 novel written by English author Mary Shelley. Frankenstein tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific experiment. Shelley started writing the story when she was 18, and the first edition was published anonymously in London on 1 January 1818, when she was 20. Her name first appeared in the second edition, which was published in Paris in 1821.

St. Irvyne; or, The Rosicrucian: A Romance is a Gothic horror novel written by Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1810 and published by John Joseph Stockdale in December of that year, dated 1811, in London anonymously as "by a Gentleman of the University of Oxford" while the author was an undergraduate. The main character is Wolfstein, a solitary wanderer, who encounters Ginotti, an alchemist of the Rosicrucian or Rose Cross Order who seeks to impart the secret of immortality. The book was reprinted in 1822 by Stockdale and in 1840 in The Romancist and the Novelist's Library: The Best Works of the Best Authors, Vol. III, edited by William Hazlitt. The novella was a follow-up to Shelley's first prose work, Zastrozzi, published earlier in 1810. St. Irvyne was republished in 1986 by Oxford University Press as part of the World's Classics series along with Zastrozzi and in 2002 by Broadview Press.

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The English word to describe such a work derives from the Italian: novella for "new", "news", or "short story ", itself from the Latin: novella, a singular noun use of the neuter plural of novellus, diminutive of novus, meaning "new". According to Margaret Doody, the novel has "a continuous and comprehensive history of about two thousand years", with its origins in the Ancient Greek and Roman novel, Medieval Chivalric romance, and in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance novella. The ancient romance form was revived by Romanticism, in the historical romances of Walter Scott and the Gothic novel. Some novelists, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Ann Radcliffe, and John Cowper Powys, preferred the term "romance". M. H. Abrams and Walter Scott have argued that a novel is a fiction narrative that displays a realistic depiction of the state of a society, while the romance encompasses any fictitious narrative that emphasizes marvellous or uncommon incidents. Works of fiction that include marvellous or uncommon incidents are also novels, including Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, and Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. Such "romances" should not be confused with the genre fiction romance novel, which focuses on romantic love.

Selina Davenport was an English novelist, briefly married to the miscellanist and biographer Richard Alfred Davenport. Her eleven published novels have been recently described as "effective if stereotyped".

Catherine Cuthbertson was a British novelist published in London in the early 19th century. She may also have written an unpublished 1803 play under the name "Miss Cuthbertson".

Dean & Son was a 19th-century London publishing firm, best known for making and mass-producing moveable children's books and toy books, established around 1800. Thomas Dean founded the firm, probably in the late 1790s, bringing to it innovative lithographic printing processes. By the time his son George became a partner in 1847, the firm was the preeminent publisher of novelty children's books in London. The firm was first located on Threadneedle Street early in the century; it moved to Ludgate Hill in the middle of the century, and then to Fleet Street from 1871 to 1890. In the mid-20th century the firm published books by Enid Blyton and children's classics in the Dean's Classics series.

Anna Millikin was a teacher and author of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. She was one of the earliest Irish women to write Gothic novels and established the literary periodical the Casket or Hesperian Magazine.

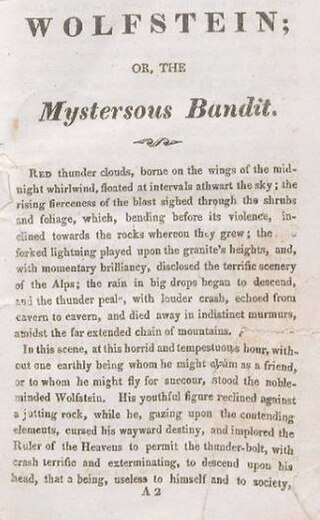

Wolfstein; or, The Mysterious Bandit is an 1822 chapbook based on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1811 Gothic horror novel St. Irvyne; or, The Rosicrucian.

Wolfstein, The Murderer; or, The Secrets of a Robber's Cave is an 1850 chapbook based on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1811 Gothic horror novel St. Irvyne; or, The Rosicrucian.

Romance, is a "a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvellous and uncommon incidents". This genre contrasted with the main tradition of the novel, which realistically depict life. These works frequently, but not exclusively, take the form of the historical novel. Walter Scott describes romance as a "kindred term", and many European languages do not distinguish between romance and novel: "a novel is le roman, der Roman, il romanzo".

Mary Julia Young was a prolific novelist, poet, translator, and biographer, active in the Romantic period, who published the bulk of her works with market-driven publishers James Fletcher Hughes and William Lane of the Minerva Press. She is of particular interest as an example of a professional woman writer in "a market of mass novel production."

References

- ↑ Tim Killick (23 May 2016). British Short Fiction in the Early Nineteenth Century: The Rise of the Tale. Routledge. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-317-17146-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alison Milbank (2010). "Gothic Satires, Histories, and Chap-books". Adam Matthew Publications. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 Angela Koch (2002). "Gothic Bluebooks in the Princely Library of Corvey and Beyond". Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text 9. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 William Watt (1967). "Shilling Shockers of the Gothic School". Russel & Russel. Print.

- 1 2 Chris Baldick (1992). "The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales". Oxford University Press. Print.

- ↑ Frederick Frank (1987). "The First Gothics". Garland Publishing. Print.

- 1 2 Peter Haining (1972). "Great British Tales of Terror". The Garden City Press Limited. Print.

- 1 2 Frederick Frank (1998). "Gothic Gold: The Sadleir-Black Gothic Collection". The American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ↑ "Gothic Stories. Sir Bertrand's adventures in a ruinous castle: The story of Fitzalan: The adventure James III. of Scotland had with the weird sisters, In The Dreadful Wood Of Birnan: The story of Raymond castle: The ruin of the House of Albert: and Mary, a fragment". London. 1800.Print.