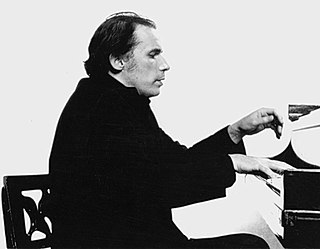

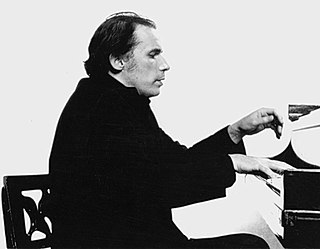

Glenn Herbert Gould was a Canadian classical pianist. He was among the most famous and celebrated pianists of the 20th century, and was renowned as an interpreter of the keyboard works of Johann Sebastian Bach. Gould's playing was distinguished by remarkable technical proficiency and a capacity to articulate the contrapuntal texture of Bach's music.

Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988), is a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held that parodies of public figures, even those intending to cause emotional distress, are protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Entertainment law, also referred to as media law, is legal services provided to the entertainment industry. These services in entertainment law overlap with intellectual property law. Intellectual property has many moving parts that include trademarks, copyright, and the "right of publicity". However, the practice of entertainment law often involves questions of employment law, contract law, torts, labor law, bankruptcy law, immigration, securities law, security interests, agency, right of privacy, defamation, advertising, criminal law, tax law, International law, and insurance law.

Personality rights, sometimes referred to as the right of publicity, are rights for an individual to control the commercial use of their identity, such as name, image, likeness, or other unequivocal identifiers. They are generally considered as property rights, rather than personal rights, and so the validity of personality rights of publicity may survive the death of the individual to varying degrees, depending on the jurisdiction.

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), originally written to guarantee individual rights of everyone everywhere; while right to privacy does not appear in the document, many interpret this through Article 12, which states: "No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks."

Jock Carroll was a Canadian writer, journalist and photographer who worked for the Canadian media, including the Toronto Telegram.

Privacy laws of the United States deal with several different legal concepts. One is the invasion of privacy, a tort based in common law allowing an aggrieved party to bring a lawsuit against an individual who unlawfully intrudes into their private affairs, discloses their private information, publicizes them in a false light, or appropriates their name for personal gain.

In United States law, the term color of law denotes the "mere semblance of legal right," the "pretense or appearance of" right; hence, an action done under color of law adjusts (colors) the law to the circumstance, yet said apparently legal action contravenes the law. Under color of authority is a legal phrase used in North America indicating that a person is claiming or implying the acts they are committing are related to and legitimized by his or her role as an agent of governmental power.

Krouse v. Chrysler Canada Ltd. is generally thought to be the first case to clearly acknowledge the existence in Canada of a tort of appropriation of personality.

"Author's rights" is a term frequently used in connection with laws about intellectual property.

The intellectual property rights on photographs are protected in different jurisdictions by the laws governing copyright and moral rights. In some cases photography may be restricted by civil or criminal law. Publishing certain photographs can be restricted by privacy or other laws. Photography can be generally restricted in the interests of public morality and the protection of children.

Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Co., 433 U.S. 562 (1977), was an important U.S. Supreme Court case concerning rights of publicity. The Court held that the First and Fourteenth Amendments do not immunize the news media from civil liability when they broadcast a performer's entire act without his consent, and the Constitution does not prevent a state from requiring broadcasters to compensate performers. It was the first time the Supreme Court heard a case on rights of publicity.

Moral rights in United Kingdom law are parts of copyright law that protect the personal interests of the author of a copyrighted work, as well as the economic interests protected by other elements of copyright. Found in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, the moral rights are the right to be identified as the author of a work, known as the right of paternity, the right to object to derogatory treatment of a work, known as the right of integrity, the right not to be identified as the author of someone else's work, and the right to privacy. The right of paternity exists for the entire copyright term, and requires individuals who commercially broadcast, sell, perform or exhibit literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works to identify the author of the work – but this does not apply to things such as typefaces, encyclopaedias or works subject to crown copyright.

Authorship and ownership in copyright law in Canada is an important and complex topic which lies at the nexus between Canada's Copyright Act, an important body of case law, and a number of compelling policy motives. Analysis of authorship and ownership of copyrightable works in Canada can proceed by examination of the rules determining the initial allocation of copyrights, rules governing subsequent changes in ownership, and finally rules governing complex works such as compilations.

Salinger v. Random House, Inc., 811 F.2d 90 is a United States case on the application of copyright law to unpublished works. In a case about author J. D. Salinger's unpublished letters, the Second Circuit held that the right of an author to control the way in which their work was first published took priority over the right of others to publish extracts or close paraphrases of the work under "fair use". In the case of unpublished letters, the decision was seen as favoring the individual's right to privacy over the public right to information. However, in response to concerns about the implications of this case on scholarship, Congress amended the Copyright Act in 1992 to explicitly allow for fair use in copying unpublished works, adding to 17 U.S.C. 107 the line, "The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors."

Stoddart Publishing was a Canadian book publisher and distributor, owned by Jack Stoddart, which ceased operations in 2002.

PJS v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2016] UKSC 26 is a UK constitutional law case in which an anonymised privacy injunction was obtained by a claimant, identified in court documents as "PJS", to prohibit publication of the details of a sexual encounter between him and two other people. Media outside England and Wales identified PJS as David Furnish.

Copyright protection is available to the creators of a range of works including literary, musical, dramatic and artistic works. Recognition of fictional characters as works eligible for copyright protection has come about with the understanding that characters can be separated from the original works they were embodied in and acquire a new life by featuring in subsequent works.

Post-mortem privacy is a person's ability to control the dissemination of personal information after death. An individual's reputation and dignity after death is also subject to post-mortem privacy protections. In the US, no federal laws specifically extend post-mortem privacy protection. At the state level, privacy laws pertaining to the deceased vary significantly, but in general do not extend any clear rights of privacy beyond property rights. The relative lack of acknowledgment of post-mortem privacy rights has sparked controversy, as rapid technological advancements have resulted in increased amounts of personal information stored and shared online.

Celebrity privacy refers to the right of celebrities and public figures, largely entertainers, athletes or politicians, to withhold the information they are unwilling to disclose. This term often pertains explicitly to personal information, which includes addresses and family members, among other data for personal identification. Different from the privacy of the general public, 'Celebrity Privacy' is considered as "controlled publicity," challenged by the press and the fans. In addition, Paparazzi make commercial use of their private data.