The orca, or killer whale, is a toothed whale and the largest member of the oceanic dolphin family. It is the only extant species in the genus Orcinus and is recognizable by its black-and-white patterned body. A cosmopolitan species, it is found in diverse marine environments, from Arctic to Antarctic regions to tropical seas.

Orcinus is a genus of Delphinidae, the family of carnivorous marine mammals known as dolphins. It includes the largest delphinid species, Orcinus orca, known as the orca or killer whale. Two extinct species are recognised, Orcinus paleorca and O. citoniensis, describing fossilised remains of the genus. The other extinct species O. meyeri is disputed.

The false killer whale is a species of oceanic dolphin that is the only extant representative of the genus Pseudorca. It is found in oceans worldwide but mainly in tropical regions. It was first described in 1846 as a species of porpoise based on a skull, which was revised when the first carcasses were observed in 1861. The name "false killer whale" comes from having a skull similar to the orca, or killer whale.

A5 Pod is a name given to a group of orcas found off the coast of British Columbia, Canada. It is part of the northern resident population of orcas—a name given to the fish-eating orcas found in coastal waters ranging from mid-Vancouver Island in British Columbia up through Haida Gwaii and into the southeastern portions of Alaska. The orcas of the Northern Resident community are divided into vocally distinctive clans known as the A clan, the G clan, and the R clan. Members of the A5 Pod belong to the A clan. As of 2013, A5 Pod consisted of 10 members.

Corky II, often referred to as just Corky, is a female captive orca from the A5 Pod of northern resident orcas. At approximately the age of four, Corky was captured from Pender Harbour off the coast of British Columbia on 11 December 1969. She has lived at SeaWorld San Diego in San Diego, California since 21 January 1987. As of 2024, she is the oldest and longest kept captive orca. SeaWorld San Diego celebrates her birthday on 1st January every year.

Kasatka was a wild caught female orca who lived at SeaWorld San Diego.

Namu was a male orca unintentionally captured in 1965 from the C1 Pod of the northern resident community. He was the first captive orca to perform with a human in the water. He was the subject of much media attention, including a starring role in the 1966 film Namu, the Killer Whale. Namu's captivity introduced thousands of people to orcas, and soon aquariums all over the world sought to establish captive orcas in their parks.

The A30 matriline is the name given to the most commonly seen orca matriline in British Columbia. The matriline is currently made of 3 generations, with a total of 12 individuals. It is one of the 3 matrilines in A1 pod, one of the 10 pods of the A-clan. The matriline was present in over 60% of all of the encounters in the Johnstone Strait region, making it one of the best known matrilines. The group's size has increased, from 6 in the mid-1970s to 10 as of 2013 then 12 in 2017. It is most frequently seen in Johnstone Strait from late spring to early fall, often traveling with other pods of the Northern Resident Community.

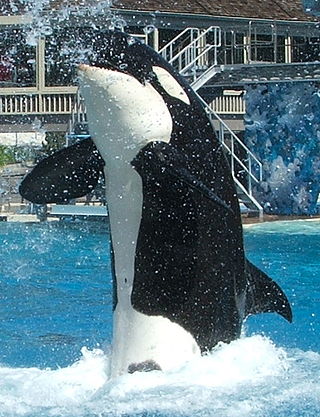

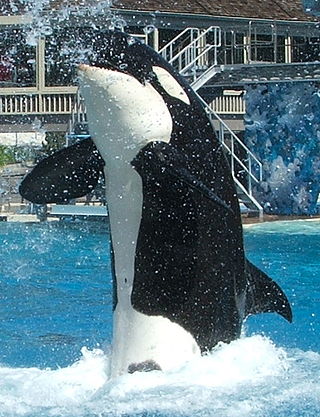

Dozens of orcas are held in captivity for breeding or performance purposes. The practice of capturing and displaying orcas in exhibitions began in the 1960s, and they soon became popular attractions at public aquariums and aquatic theme parks due to their intelligence, trainability, striking appearance, playfulness, and sheer size. As of 24 March 2024, around 55 orcas are in captivity worldwide, 33 of which were captive-born. At that time, there were 18 orcas in the SeaWorld parks.

A4 pod is a killer whale family in British Columbia. As of March 2013, it consists of three matrilines and 15 members and is the family of Springer, the first orca to be successfully reintroduced to the wild after being handled by humans. A4 pod is part of the northern resident orcas found in coastal waters ranging from mid-Vancouver Island to southeastern Alaska up through Haida Gwaii. The community is made up of three clans known as A, G and R clans, each possessing a distinctive dialect and consisting of several related pods. A4 pod belongs to the biggest clan, A clan.

Michael Andrew Bigg was an English-born Canadian marine biologist who is recognized as the founder of modern research on killer whales. With his colleagues, he developed new techniques for studying killer whales and, off British Columbia and Washington, conducted the first population census of the animals anywhere in the world. Bigg's work in wildlife photo-identification enabled the longitudinal study of individual killer whales, their travel patterns, and their social relationships in the wild, and revolutionized the study of cetaceans.

The southern resident orcas, also known as the southern resident killer whales (SRKW), are the smallest of four communities of the exclusively fish-eating ecotype of orca in the northeast Pacific Ocean. The southern resident orcas form a closed society with no emigration or dispersal of individuals, and no gene flow with other orca populations. The fish-eating ecotype was historically given the name 'resident,' but other ecotypes named 'transient' and 'offshore' are also resident in the same area.

A1 pod is a killer whale family in British Columbia. It currently consists of 3 matrilines and 20 members and is the most commonly encountered pod in the Northern resident killer whale community. This community is found in coastal waters ranging from mid-Vancouver Island up through the Queen Charlotte Islands, although A1 pod has yet to be seen this far north. The community is made up of three clans known as A, G and R clans, each possessing a distinctive dialect and consisting of several related pods. A1 pod belongs to the biggest clan, A clan.

Morgan is a female orca who was rescued in the Wadden Sea, off the northwestern coast of the Netherlands in June 2010. She was found in an unhealthy condition, severely underweight and malnourished. She lived several months at the Dolfinarium Harderwijk in the Netherlands. After it became clear that the basin at Dolfinarium was too small, multiple options were considered, including releasing Morgan and transferring her to another facility. Over a year later, after litigation and debate between scientists, a Dutch court ruled that she was to be moved. Morgan was transported to the Loro Parque in Tenerife, Spain in November 2011.

Tahlequah, also known as J35, is an orca of the southern resident community in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. She has given birth to four known offspring, a male (Notch) in 2010, a female (Tali) in 2018, another male (Phoenix) in 2020, and a new unnamed calf in 2024. Her second calf, Tali, died shortly after birth and J35 carried her body for 17 days in an apparent show of grief that attracted international attention.

Northern resident orcas, also known as northern resident killer whales (NRKW), are one of four separate, non-interbreeding communities of the exclusively fish-eating ecotype of orca in the northeast portion of the North Pacific Ocean. They live primarily off the coast of British Columbia (BC), Canada, and also travel to southeastern Alaska and northern Washington state in the United States. The northern resident population consists of three clans that consists of several pods with one or more matrilines within each pod. The northern residents are genetically distinct from the southern resident orcas and their calls are also quite distinct.

Orcas or killer whales have a cosmopolitan distribution and several distinct populations or types have been documented or suggested. Three to five types of orcas may be distinct enough to be considered different races, subspecies, or possibly even species. The IUCN reported in 2008, "The taxonomy of this genus is clearly in need of review, and it is likely that O. orca will be split into a number of different species or at least subspecies over the next few years." Although large variation in the ecological distinctiveness of different orca groups complicate simple differentiation into types. Mammal-eating orcas in different regions were long thought likely to be closely related, but genetic testing has refuted this hypothesis.

Few animals have a menopause: humans are joined by just four other species in which females live substantially longer than their ability to reproduce. The others are all cetaceans: beluga whales, narwhals, orcas and short-finned pilot whales. There are various theories on the origin and process of the evolution of menopause. These attempt to suggest evolutionary benefits to the human species stemming from the cessation of women's reproductive capability before the end of their natural lifespan. Explanations can be categorized as adaptive and non-adaptive:

The waters of the Salish Sea, on the west coast of North America, are home to several ecologically distinct populations of orcas. The area supports three major ecotypes of orcas: northern residents, southern residents, and transients. A fourth ecotype, the offshore orcas, occasionally venture into nearshore waters. Little to no interaction occurs between the different ecotypes. Resident and transient orcas have not been observed interbreeding, although occasional brief interactions occur.