The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

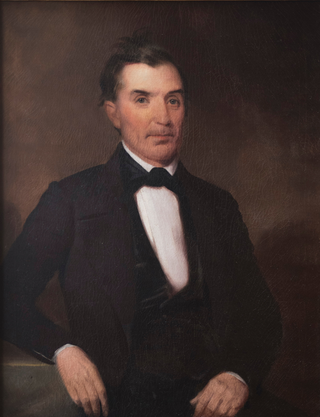

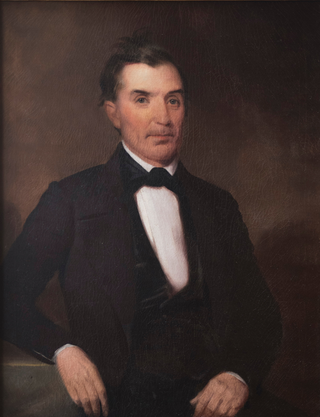

Isaac Franklin was an American slave trader and plantation owner. Born to wealthy planters in what would become Sumner County, Tennessee, he assisted his brothers in trading slaves and agricultural surplus along the Mississippi River in his youth, before briefly serving in the Tennessee militia during the War of 1812. He returned to slave trading soon after the war, buying enslaved people in Virginia and Maryland, before marching them in coffles to sale at Natchez, Mississippi. He introduced John Armfield to the slave trade, and with him founded the Franklin & Armfield partnership in 1828, which would go on to become one of the largest slave trading firms in the United States. With a base of operations in Alexandria, D.C., the company shipped massive numbers of the enslaved by land and sea to markets at Natchez and New Orleans.

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. In 1830, enslaved African Americans represented 24 percent of Kentucky's population, a share that had declined to 19.5 percent by 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Most enslaved people were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington and in the hemp- and tobacco-producing Bluegrass Region and Jackson Purchase. Other enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties, where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Relatively few people were held in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky; they served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

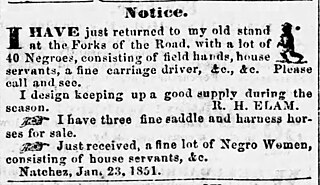

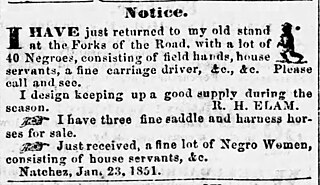

The Forks of the Road was a slave market in Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. The Forks of the Road market was located about a mile from downtown Natchez at the intersection of Liberty Road and Washington Road, which has since been renamed to D'Evereux Drive in one direction and St. Catherine Street in the other. The market differed from many other slave sellers of the day by offering individuals on a first-come first-serve basis rather than selling them at auction, either singly or in lots. At one time the Forks of the Road was the second-largest slave market in the United States, trailing only New Orleans.

A coffle, sometimes called a platoon or a drove, was a group of enslaved people chained together and marched from one place to another by owners or slave traders. These troupes, sometimes called shipping lots before they were moved, ranged in size from a fewer than a dozen to 200 or more enslaved people.

This is a bibliography of works regarding the internal or domestic slave trade in the United States.

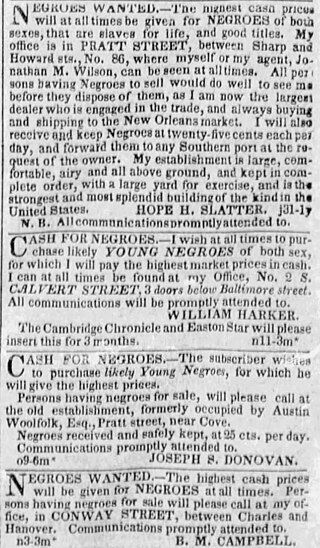

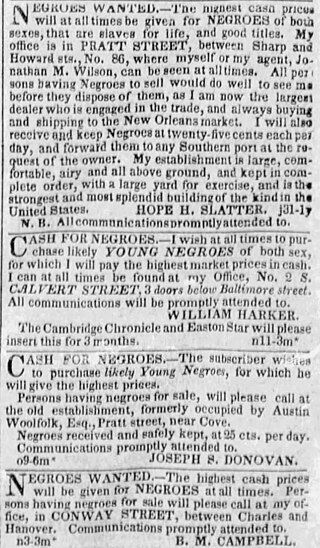

Bernard Moore Campbell and Walter L. Campbell operated an extensive slave-trading business in the antebellum U.S. South. B. M. Campbell, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Joseph S. Donovan, and Hope H. Slatter, has been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9,000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans." Bernard and Walter were brothers.

Slave markets and slave jails in the United States were places used for the slave trade in the United States from the founding in 1776 until the total abolition of slavery in 1865. Slave pens, also known as slave jails, were used to temporarily hold enslaved people until they were sold, or to hold fugitive slaves, and sometimes even to "board" slaves while traveling. Slave markets were any place where sellers and buyers gathered to make deals. Some of these buildings had dedicated slave jails, others were negro marts to showcase the slaves offered for sale, and still others were general auction or market houses where a wide variety of business was conducted, of which "negro trading" was just one part.

Theophilus Freeman was a 19th-century American slave trader of Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi. He was known in his own time as wealthy and problematic. Freeman's business practices were described in two antebellum American slave narratives—that of John Brown and that of Solomon Northup—and he appears as a character in both filmed dramatizations of Northrup's Twelve Years a Slave.

William A. Pullum was a 19th-century American slave trader, and a principal of Griffin & Pullum. He was based in Lexington, Kentucky, and for many years purchased, imprisoned, and shipped enslaved people from Virginia and Kentucky south to the Forks-of-the-Road slave market in Natchez, Mississippi.

James McMillin was an American tavern keeper and slave trader of Kentucky. He was implicated in more than one case of attempted kidnapping into slavery. In 1857 Memphis slave trader Isaac Bolton shot McMillin several times over an unprofitable trade. McMillin died hours later in the home of Memphis slave trader Nathan Bedford Forrest. His last name is very often spelled McMillan or McMillen; this article uses the spelling that appears on his grave marker and hometown newspaper.

George Kephart was a 19th-century American slave trader, land owner, farmer, and philanthropist. A native of Maryland, he was an agent of the interstate trading firm Franklin & Armfield early in his career, and later occupied, owned, and finally leased out that company's infamous slave jail in Alexandria. In 1862, Henry Wilson of Massachusetts mentioned Kephart by name in a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate as one of the traders who had "polluted the capital of the nation with this brutalizing traffic" of selling people.

Seth Woodroof was a slave trader based in Lynchburg in central Virginia, United States. He was an interstate trader who ran what the Lynchburg Museum called the "most active and infamous" slave pen in the city. He is believed to have been actively trading from approximately 1830 until the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Woodroof sat on the Lynchburg city council from 1858 to 1865.

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

John T. Hatcher was a 19th-century American slave trader. He was the younger brother of slave trader C. F. Hatcher; they worked together in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans, Louisiana. Two days before Christmas 1858, he whipped an enslaved woman to death and fled New Orleans to avoid the consequences.

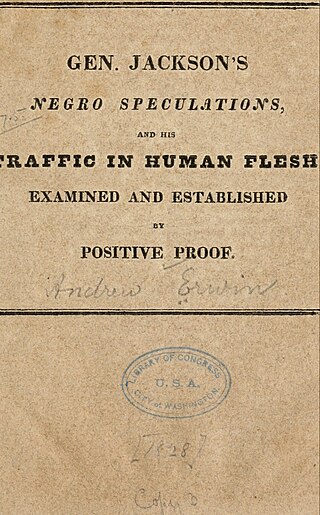

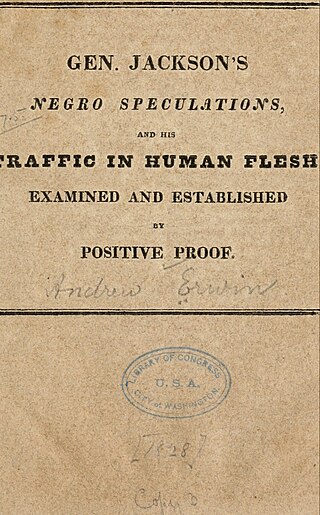

The question of whether Andrew Jackson had been a "negro trader" was a campaign issue during the 1828 United States presidential election. Jackson denied the charges, and the issue failed to connect with the electorate. However, Jackson had indeed been a "speculator in slaves," participating in the interstate slave trade between Nashville, Tennessee and the slave markets of the lower Mississippi River valley at Natchez and New Orleans.

Matthew Garrison was an American interstate slave trader who bought in Kentucky and sold in Louisiana and Mississippi from the 1830s into the 1860s. He ran one of the major slave jails in antebellum Louisville, Kentucky. Garrison left his entire estate to two women of color and their combined six children by him.

Sowell Woolfolk was a 19th-century American businessman and politician known for serving as a Georgia state legislator and U.S. state militia officer, working as a slave trader, and dying in a duel at Fort Mitchell, Alabama in 1832.

John W. Lindsey was a slave trader based in Montgomery, Alabama, United States in the 1840s and 1850s.