Related Research Articles

Year 1201 (MCCI) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar.

Constance I was the Queen of Sicily from 1194 until her death and Holy Roman Empress from 1191 to 1197 as the wife of Emperor Henry VI.

Boniface I, usually known as Boniface of Montferrat, was the ninth Marquis of Montferrat, a leader of the Fourth Crusade (1201–04) and the king of Thessalonica.

The Kingdom of Sicily was a state that existed in Sicily and the south of the Italian Peninsula plus, for a time, in Northern Africa from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was a successor state of the County of Sicily, which had been founded in 1071 during the Norman conquest of the southern peninsula. The island was divided into three regions: Val di Mazara, Val Demone and Val di Noto.

Margaritus of Brindisi, called "the new Neptune", was the last great ammiratus ammiratorum of the Kingdom of Sicily. Following in the footsteps of Christodulus, George of Antioch, and Maio of Bari, Margaritus commanded the kingdom's fleets during the reigns of William II (1166–1189) and Tancred (1189–1194). He probably began as a Greek pirate and gradually rose to the rank of privateer before becoming a permanent admiral of the navy. In 1185, he became the first count palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos. In 1192, he became the first Count of Malta.

Walter of Palear was the chancellor of the Kingdom of Sicily under Queen Constance and the Emperor Henry VI. He was also the bishop of Troia (1189–1208) and later bishop of Catania.

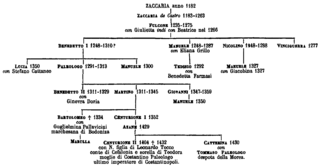

Benedetto I Zaccaria was an Italian admiral of the Republic of Genoa. He was the Lord of Phocaea and first Lord of Chios, and the founder of Zaccaria fortunes in Byzantine and Latin Greece. He was, at different stages in his life, a diplomat, adventurer, mercenary, and statesman.

The County of Malta was a feudal lordship of the Kingdom of Sicily, relating to the islands of Malta and Gozo. Malta was essentially a fief within the kingdom, with the title given by Tancred of Sicily the Norman king of Sicily to Margaritus of Brindisi in 1192 who earned acclaim as the Grand Admiral of Sicily. Afterwards the fiefdom was passed from nobleman to nobleman remaining as a family possession in a few instances. It was used mainly as a bargaining tool in Sicilian politics leading to a rather turbulent history. The fiefdom was elevated to a Marquisate in 1392 and either title was no longer used after 1429.

Henry, known as Enrico Pescatore, was a Genoese adventurer, privateer and pirate active in the Mediterranean at the beginning of the thirteenth century. His real name is said to have been Erico or Arrigo di Castro or del Castello di Candia.

The Massacre of the Latins was a large-scale massacre of the Roman Catholic inhabitants of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, by the Eastern Orthodox population of the city in April 1182.

The Treaty of Nymphaeum was a trade and defense pact signed between the Empire of Nicaea and the Republic of Genoa in Nymphaion in March 1261. This treaty would have a major impact on both the restored Byzantine Empire and the Republic of Genoa that would later dictate their histories for several centuries to come.

Roger de Flor, also known as Ruggero/Ruggiero da Fiore or Rutger von Blum or Ruggero Flores, was an Italian military adventurer and condottiere active in Aragonese Sicily, Italy, and the Byzantine Empire. He was the commander of the Great Catalan Company and held the title Count of Malta.

Henry VI, a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was also King of Sicily as the husband and co-ruler of Queen Constance I.

Alamanno da Costa was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of Syracuse in the Kingdom of Sicily, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstanding conflict with Pisa and in the origin of its conflict with Venice. The historian Ernst Kantorowicz called him a "famous prince of pirates".

Ottone del Carretto, a patron of troubadours and an imperialist, was the margrave of Savona (c.1185–91) and podestà of the Republic of Genoa (1194–95) and of Asti (1212). He was the founder of the Del Carretto family.

The Genoese navy was the naval contingent of the Republic of Genoa's military. From the 11th century onward the Genoese navy protected the interests of the republic and projected its power throughout the Mediterranean and Black Seas. It played a crucial role in the history of the republic as a thalassocracy and a maritime trading power.

In 1268, the Byzantine Empire and the Republic of Venice agreed to temporarily end hostilities which had erupted after the Byzantine recovery of Constantinople by Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261.

Guglielmo Boccanegra was a Genoese statesman, the first capitano del popolo of the Republic of Genoa, from 1257 to 1262, exercising a real lordship, assisted in the government by a council of 32 elders.

Simone Guercio was a Genoese noble and military commander and official in the service of the Republic of Genoa during the third quarter of the 13th century.

References

- 1 2 Matthew (1992), p. 295.

- ↑ Jamil & Johns (2016), pp. 147–148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jamil & Johns (2016), pp. 118–120.

- ↑ Jamil & Johns (2016), p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Basso (2002).

- ↑ Basso (2015).

- ↑ Houben (1993).

- 1 2 3 Fotheringham (1910), pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Brand (1968), pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Penna (2017), p. 36.

- ↑ Jamil & Johns (2016), pp. 144–149.

- ↑ Jamil & Johns (2016), p. 119, citing Van Cleve (1937), p. 123.

- ↑ Matthew (1992), pp. 303–304.

Works cited

- Basso, Enrico (2002). "Grasso, Guglielmo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 58: Gonzales–Graziani (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Basso, Enrico (2015). "Pescatore, Enrico". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 82: Pazzi–Pia (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Brand, Charles M. (1968). Byzantium Confronts the West, 1180–1204. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fotheringham, J. K. (1910). "Genoa and the Fourth Crusade". The English Historical Review. 25 (97): 26–57. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXV.XCVII.26. JSTOR 549792.

- Houben, Hubert (1993). "Enrico di Malta". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 42: Dugoni–Enza (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Jamil, Nadia; Johns, Jeremy (2016). "A New Latin-Arabic Document from Norman Sicily (November 595 H/1198 CE)". In Maurice A. Pomerantz; Aram Shahin (eds.). The Heritage of Arabo-Islamic Learning: Studies Presented to Wadad Kadi. Brill. pp. 111–166.

- Matthew, Donald (1992). The Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Penna, Daphne (2017). "Piracy and Reprisal in Byzantine Waters: Resolving a Maritime Conflict between Byzantines and Genoese at the End of the Twelfth Century". Comparative Legal History. 5 (1): 36–52. doi: 10.1080/2049677x.2017.1311549 .

- Van Cleve, Thomas C. (1937). Markward of Anweiler: His Life and Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.