Guglielmo Gratarolo or Grataroli or Guilelmus Gratarolus (16 May 1516, Bergamo - 16 April 1568, Basel) was an Italian doctor and alchemist.

Guglielmo Gratarolo or Grataroli or Guilelmus Gratarolus (16 May 1516, Bergamo - 16 April 1568, Basel) was an Italian doctor and alchemist.

Gratorolo studied in Padua and Venice.

A Calvinist, Gratarolo sought refuge in Graubünden, Strasbourg, and finally settled in Basel in 1552. There, he taught medicine and edited a number works, particularly alchemical ones, notable among them the 1561 collection Verae alchemiae artisque metallicae published by the printer Henricus Petrus, and reprinted in 1572.

Verae alchemiae artisque metallica relied heavily on the earlier printed alchemical collection De Alchemia and was in turn heavily relied upon for the Theatrum Chemicum . Gratorolo omitted only the Tabula Smaragdina and Ortulanus' commentary on it from volume 1; these had been published separately a year earlier in 1560, although falsely attributed to Johannes de Garlandia. Above all, Gratorolo wanted to publish the works of Pseudo-Lull and Pseudo-Geber. The contents of the 1561 edition are as follows:. [1]

Volume 1:

Volume 2:

Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

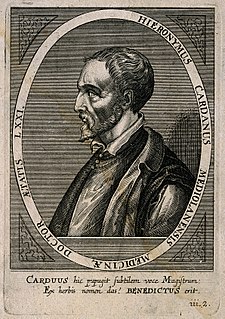

Gerolamo Cardano was an Italian polymath, whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, physician, biologist, physicist, chemist, astrologer, astronomer, philosopher, writer, and gambler. He was one of the most influential mathematicians of the Renaissance, and was one of the key figures in the foundation of probability and the earliest introducer of the binomial coefficients and the binomial theorem in the Western world. He wrote more than 200 works on science.

Paracelsus, born Theophrastus von Hohenheim, was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

Medieval medicine in Western Europe was composed of a mixture of pseudoscientific ideas from antiquity. In the Early Middle Ages, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, standard medical knowledge was based chiefly upon surviving Greek and Roman texts, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere. Medieval medicine is widely misunderstood, thought of as a uniform attitude composed of placing hopes in the church and God to heal all sicknesses, while sickness itself exists as a product of destiny, sin, and astral influences as physical causes. On the other hand, medieval medicine, especially in the second half of the medieval period, became a formal body of theoretical knowledge and was institutionalized in the universities. Medieval medicine attributed illnesses, and disease, not to sinful behaviour, but to natural causes, and sin was connected to illness only in a more general sense of the view that disease manifested in humanity as a result of its fallen state from God. Medieval medicine also recognized that illnesses spread from person to person, that certain lifestyles may cause ill health, and some people have a greater predisposition towards bad health than others.

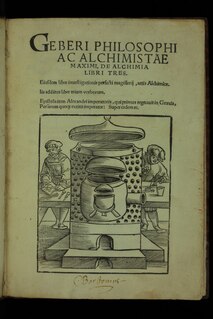

Pseudo-Geber refers to a corpus of Latin alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries, attributed to Geber, an early alchemist of the Islamic Golden Age. The most important work of the Latin pseudo-Geber corpus is Summa perfectionis magisterii, likely written slightly before 1310, whose actual author has been tentatively identified as Paul of Taranto. The work was influential in the domain of alchemy and metallurgy in late medieval Europe.

Mathias de l'Obel, Mathias de Lobel or Matthaeus Lobelius was a Flemish physician and plant enthusiast who was born in Lille, Flanders, in what is now Hauts-de-France, France, and died at Highgate, London, England. He studied at the University of Montpellier and practiced medicine in the low countries and England, including positions as personal physicians to two monarchs. A member of the sixteenth-century Flemish School of Botany, he wrote a series of major treatises on plants in both Latin and Dutch. He was the first botanist to appreciate the distinction between monocotyledons and dicotyledons. The Lobelia plant is named after him.

In ceremonial magic, a magical formula or a word of power is a word that is believed to have specific supernatural effects. They are words whose meaning illustrates principles and degrees of understanding that are often difficult to relay using other forms of speech or writing. It is a concise means to communicate very abstract information through the medium of a word or phrase.

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, which recently had come under Christian rule following their reconquest in the late 11th century. These areas had been under Muslim rule for a considerable time, and still had substantial Arabic-speaking populations to support their search. The combination of this accumulated knowledge and the substantial numbers of Arabic-speaking scholars there made these areas intellectually attractive, as well as culturally and politically accessible to Latin scholars. A typical story is that of Gerard of Cremona, who is said to have made his way to Toledo, well after its reconquest by Christians in 1085, because he

arrived at a knowledge of each part of [philosophy] according to the study of the Latins, nevertheless, because of his love for the Almagest, which he did not find at all amongst the Latins, he made his way to Toledo, where seeing an abundance of books in Arabic on every subject, and pitying the poverty he had experienced among the Latins concerning these subjects, out of his desire to translate he thoroughly learnt the Arabic language....

Jean de Roquetaillade, also known as John of Rupescissa, was a French Franciscan alchemist and eschatologist.

Lucilia is believed to have been the wife of the Roman philosopher Lucretius, though there is little evidence of their relationship, let alone marriage. Moreover, the name 'Lucilia' was not associated with Lucretius until many centuries after his death. In Walter Map's twelfth century work titled De nugis curialium, 'Lucilia' is the name of a woman who murders her husband by giving him a potion that causes him to go insane. It wasn't until 1511, in Pius's vita, that the name 'Lucilia' became associated with Lucretius. Some have even questioned whether this association was made-up for the sake of writing, that is, to maintain literary style.

Dirk Martens was a printer and editor in the County of Flanders. He published over fifty books by Erasmus and the very first edition of Thomas More's Utopia. He was the first to print Greek and Hebrew characters in the Netherlands. In 1856 a statue of Martens was erected on the main square of the town of his birth, Aalst.

Janus Cornarius was a Saxon humanist and friend of Erasmus. A gifted philologist, Cornarius specialized in editing and translating Greek and Latin medical writers with "prodigious industry," taking a particular interest in botanical pharmacology and the effects of environment on illness and the body. Early in his career, Cornarius also worked with Greek poetry, and later in his life Greek philosophy; he was, in the words of Friedrich August Wolf, "a great lover of the Greeks." Patristic texts of the 4th century were another of his interests. Some of his own writing is extant, including a book on the causes of plague and a collection of lectures for medical students.

Theatrum Chemicum is a compendium of early alchemical writings published in six volumes over the course of six decades. The first three volumes were published in 1602, while the final sixth volume was published in its entirety in 1661. Theatrum Chemicum remains the most comprehensive collective work on the subject of alchemy ever published in the Western world.

Hadrianus Junius (1511–1575), also known as Adriaen de Jonghe, was a Dutch physician, classical scholar, translator, lexicographer, antiquarian, historiographer, emblematist, school rector, and Latin poet.

The literature of Sardinia is the literary production of Sardinian authors, as well as the literary production generally referring to Sardinia as argument, written in various languages.

The Paenitentiale Ecgberhti is an early medieval penitential handbook composed around 740, possibly by Archbishop Ecgberht of York.

De Alchemia is an early collection of alchemical writings first published by Johannes Petreius in Nuremberg in 1541. A second edition was published in Frankfurt in 1550 by the printer Cyriacus Jacobus.

The Deutsche Theatrum Chemicum is a collection of alchemical texts, predominantly in German translation, which was published in Nuremberg in three volumes by Friedrich Roth-Scholtz (1687–1736), the publisher, printer and bibliographer.