Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was a German transatlantic ocean liner in service from 1897 to 1914, when she was scuttled in battle. She was the largest ship in the world for a time, and held the Blue Riband until Cunard Line’s RMS Lusitania entered service in 1907. The vessel’s career was relatively uneventful, despite a refit in 1913.

The Cunard Line is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been registered in Hamilton, Bermuda.

The Blue Riband is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. The record is based on average speed rather than passage time because ships follow different routes. Also, eastbound and westbound speed records are reckoned separately, as the more difficult westbound record voyage, against the Gulf Stream and the prevailing weather systems, typically results in lower average speeds.

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuries after the dwindling of sporadic Viking trade with Markland, a regular and lasting transatlantic trade route was established in 1566 with the Spanish West Indies fleets, following the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

An ocean liner is a type of passenger ship primarily used for transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes. The Queen Mary 2 is the only ocean liner still in service to this day.

RMS Mauretania was a British ocean liner designed by Leonard Peskett and built by Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson on the River Tyne, England for the Cunard Line, launched on the afternoon of 20 September 1906. She was the world's largest ship until the launch of RMS Olympic in 1910. Mauretania captured the eastbound Blue Riband on the maiden return voyage in December 1907, then claimed the westbound Blue Riband for the fastest transatlantic crossing during her 1909 season. She held both speed records for 20 years.

SS Normandie was a French ocean liner built in Saint-Nazaire, France, for the French Line Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT). She entered service in 1935 as the largest and fastest passenger ship afloat, crossing the Atlantic in a record 4.14 days, and remains the most powerful steam turbo-electric-propelled passenger ship ever built.

SS Europa, later SS Liberté IMO 5607332, was a German ocean liner built for the Norddeutsche Lloyd line (NDL) to work the transatlantic sea route. Launched in 1928, she and her sister ship, Bremen, were the two most advanced, high-speed steam turbine ocean vessels in their day, with both earning the Blue Riband.

The Inman Line was one of the three largest 19th-century British passenger shipping companies on the North Atlantic, along with the White Star Line and Cunard Line. Founded in 1850, it was absorbed in 1893 into American Line. The firm's formal name for much of its history was the Liverpool, Philadelphia and New York Steamship Company, but it was also variously known as the Liverpool and Philadelphia Steamship Company, as Inman Steamship Company, Limited, and, in the last few years before absorption, as the Inman and International Steamship Company.

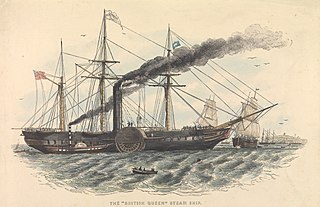

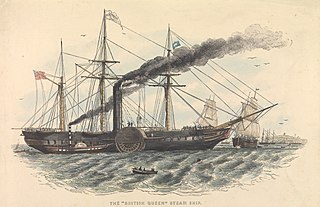

British Queen was a British passenger liner that was the second steamship completed for the transatlantic route when she was commissioned in 1839. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1839 to 1840, then being passed by the SS President. She was named in honour of Queen Victoria and owned by the British and American Steam Navigation Company. British Queen would have been the first transatlantic steamship had she not been delayed by 18 months because of the liquidation of the firm originally contracted to build her engine.

Destriero was a 67-metre (220 ft) long, 13-metre (43 ft) wide, 400-ton displacement, yacht built by Fincantieri in their Muggiano yard at La Spezia in 1991. She was fitted with three GE Aviation LM1600 gas turbines totalling 60,000-horsepower (45,000 kW), providing her with a maximum speed of 110 kilometres per hour. Destriero was built with the sponsorship of the Aga Khan IV and others specifically to cross the Atlantic Ocean in record time of 3 days and secure the Blue Riband.

City of Paris was a British passenger liner operated by the Inman Line that established that a ship driven by a screw could match the speed of the paddlers on the Atlantic crossing. Built by Tod and Macgregor, she served the Inman Line until 1884 when she was converted to a cargo ship.

The Liverpool and Great Western Steamship Company, known commonly as the Guion Line, was a British passenger service that operated the Liverpool-Queenstown-New York route from 1866 to 1894. While incorporated in Great Britain, 52% of the company's capital was from the American firm, Williams and Guion of New York. Known primarily for transporting immigrants, in 1879 the line started commissioning Blue Riband record breakers to compete against Cunard, White Star and Inman for first class passengers. The financial troubles of one of the company's major partners in 1884 forced the firm to return its latest record breaker, the Oregon, to her builders and focus again on the immigrant trade. The company suspended sailings in 1894 because of new American restrictions on immigrant traffic.

SS Oregon was a record-breaking British passenger liner that won the Blue Riband for the Guion Line as the fastest liner on the Atlantic in 1884. She was sold to the Cunard Line after a few voyages and continued to improve her passage times for her new owner. In 1885, Oregon was chartered to the Royal Navy as an auxiliary cruiser, and her success in this role resulted in the Admiralty subsidizing suitable ships for quick conversion in the event of a crisis. She returned to Cunard service in November 1885 and four months later collided with a schooner while approaching New York. Virtually all persons on board were rescued before Oregon sank. Her wreck, 18 miles south of Long Island, remains a popular diving site.

Scotia was a British passenger liner operated by the Cunard Line that won the Blue Riband in 1863 for the fastest westbound transatlantic voyage. She was the last oceangoing paddle steamer, and as late as 1874 she made Cunard's second fastest voyage. Laid up in 1876, Scotia was converted to a twin-screw cable layer in 1879. She served in her new role for twenty-five years until she was wrecked off of Guam in March 1904.

Persia was a British passenger liner operated by the Cunard Line that won the Blue Riband in 1856 for the fastest westbound transatlantic voyage. She was the first Atlantic record breaker constructed of iron and was the largest ship in the world at the time of her launch. However, the inefficiencies of paddle wheel propulsion rendered Persia obsolete and she was taken out of service in 1868 after only twelve years. Attempts to convert Persia to sail were unsuccessful and the former pride of the British merchant marine was scrapped in 1872.

The Britannia class was the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddlers that established the first year round scheduled Atlantic steamship service in 1840. By 1845, steamships carried half of the transatlantic saloon passengers and Cunard dominated this trade. While the units of the Britannia class were solid performers, they were not superior to many of the other steamers being placed on the Atlantic at that time. What made the Britannia class successful is that it was the first homogeneous class of transatlantic steamships to provide a frequent and uniform service. Britannia, Acadia and Caledonia entered service in 1840 and Columbia in 1841 enabling Cunard to provide the dependable schedule of sailings required under his mail contracts with the Admiralty. It was these mail contracts that enabled Cunard to survive when all of his early competitors failed.

The America class was the replacement for the Britannia class, the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddle steamers. Entering service starting in 1848, these six vessels permitted Cunard to double its schedule to weekly departures from Liverpool, with alternating sailings to New York. The new ships were also designed to meet new competition from the United States.

SS President was a British passenger liner that was the largest ship in the world when she was commissioned in 1840, and the first steamship to founder on the transatlantic run when she was lost at sea with all 136 onboard in March 1841. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1840 to 1841. The ship's owner, the British and American Steam Navigation Company, collapsed as a result of the disappearance.

The Virgin Atlantic Challenge Trophy is an award for the fastest trans-Atlantic crossing by a surface vessel, one of several such awards that have grown out of the contest for the prestigious Blue Riband of the Atlantic. The trophy was created following Richard Branson's record-breaking Atlantic crossing in 1986 and the refusal by the American Merchant Marine Museum to surrender the Hales Trophy, the then only official award for the Atlantic crossing record. The Virgin Atlantic Challenge Trophy is currently held by the Aga Khan's vessel, Destriero.