Related Research Articles

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk is common throughout Western Europe, where deposits underlie parts of France, and steep cliffs are often seen where they meet the sea in places such as the Dover cliffs on the Kent coast of the English Channel.

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the first President of the Palaeontographical Society.

John Phillips FRS was an English geologist. In 1841 he published the first global geologic time scale based on the correlation of fossils in rock strata, thereby helping to standardize terminology including the term Mesozoic, which he invented.

The geology of Great Britain is renowned for its diversity. As a result of its eventful geological history, Great Britain shows a rich variety of landscapes across the constituent countries of England, Wales and Scotland. Rocks of almost all geological ages are represented at outcrop, from the Archaean onwards.

The London Clay Formation is a marine geological formation of Ypresian age which crops out in the southeast of England. The London Clay is well known for its fossil content. The fossils from the lower Eocene rocks indicate a moderately warm climate, the tropical or subtropical flora. Though sea levels changed during the deposition of the clay, the habitat was generally a lush forest – perhaps like in Indonesia or East Africa today – bordering a warm, shallow ocean.

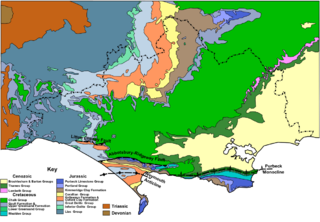

Dorset is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. Covering an area of 2,653 square kilometres (1,024 sq mi); it borders Devon to the west, Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north-east, and Hampshire to the east. The great variation in its landscape owes much to the underlying geology, which includes an almost unbroken sequence of rocks from 200 to 40 million years ago (Mya) and superficial deposits from 2 Mya to the present. In general, the oldest rocks appear in the far west of the county, with the most recent (Eocene) in the far east. Jurassic rocks also underlie the Blackmore Vale and comprise much of the coastal cliff in the west and south of the county; although younger Cretaceous rocks crown some of the highpoints in the west, they are mainly to be found in the centre and east of the county.

In Devon and Cornwall, tin coinage was a tax on refined tin, payable to the Duchy of Cornwall and administered in the Stannary Towns. The oldest surviving records of coinage show that it was collected in 1156. It was abolished by the Tin Duties Act 1838.

In geology, clay-with-flints was the name given by William Whitaker in 1861 to a peculiar deposit of stiff red, brown or yellow clay containing unworn whole flints as well as angular shattered fragments, also with a variable admixture of rounded flint, quartz, quartzite and other pebbles.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic to refer to sedimentary rocks and particles in sediment transport, whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

Heavitree stone is a type of breccia stone, red in colour, of very coarse texture and prone to weathering, which occurs naturally in the parish of Heavitree near the City of Exeter in Devon, England. It was quarried in the area from about 1350 to the 19th century, and was used to construct many of Exeter's older buildings, including Exeter Castle, the old city walls, and many of the almshouses and parish churches. Many ancient buildings in Exeter made of Heavitree stone were destroyed by enemy bombing during World War II. It was first referred to by Sir Henry De La Beche in 1839, as the "Conglomerates of Heavitree".

The geology of England is mainly sedimentary. The youngest rocks are in the south east around London, progressing in age in a north westerly direction. The Tees–Exe line marks the division between younger, softer and low-lying rocks in the south east and the generally older and harder rocks of the north and west which give rise to higher relief in those regions. The geology of England is recognisable in the landscape of its counties, the building materials of its towns and its regional extractive industries.

The Hampshire Basin is a geological basin of Palaeogene age in southern England, underlying parts of Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Dorset, and Sussex. Like the London Basin to the northeast, it is filled with sands and clays of Paleocene and younger ages and it is surrounded by a broken rim of chalk hills of Cretaceous age.

The geology of East Sussex is defined by the Weald–Artois anticline, a 60 kilometres (37 mi) wide and 100 kilometres (62 mi) long fold within which caused the arching up of the chalk into a broad dome within the middle Miocene, which has subsequently been eroded to reveal a lower Cretaceous to Upper Jurassic stratigraphy. East Sussex is best known geologically for the identification of the first dinosaur by Gideon Mantell, near Cuckfield, to the famous hoax of the Piltdown man near Uckfield.

The Dean Hill Anticline is an east-west trending fold in the Cretaceous chalk of Hampshire, England. It lies immediately to the north of the Hampshire Basin and south of Salisbury Plain.

The Alderbury-Mottisfont Syncline is an east–west trending fold in the Cretaceous chalk of Hampshire. It lies to the north of the Dean Hill Anticline and south of Salisbury Plain.

The geology of West Sussex in southeast England comprises a succession of sedimentary rocks of Cretaceous age overlain in the south by sediments of Palaeogene age. The sequence of strata from both periods consists of a variety of sandstones, mudstones, siltstones and limestones. These sediments were deposited within the Hampshire and Weald basins. Erosion subsequent to large scale but gentle folding associated with the Alpine Orogeny has resulted in the present outcrop pattern across the county, dominated by the north facing chalk scarp of the South Downs. The bedrock is overlain by a suite of Quaternary deposits of varied origin. Parts of both the bedrock and these superficial deposits have been worked for a variety of minerals for use in construction, industry and agriculture.

The Portsdown Anticline is a north-facing geological fold of Tertiary age affecting rocks in Hampshire, southern England. This upfold of the local sedimentary rock sequence is paralleled by the Bere Forest/Chichester Syncline (downfold) about 2km to its north and a postulated deep fault to the north again. Further west, this major east-west structure adopts more of a NW - SE alignment. At the surface the Portsdown Anticline is seen to affect the Chalk rocks of Late Cretaceous age at Ports Down though it is known to also affect the underlying Jurassic strata.

Sharkham Point Iron Mine was an iron mine at Sharkham Point, near the town of Brixham in Devon. The mine was worked for around 125 years and employed at its peak 100 workers. It was primarily an open cast mine, but five shafts and six adits are also mentioned in reports of the site. Some are still accessible today, but since the area was used as a rubbish tip in the 1950s and 60s, much of the archaeology has been covered over.

References

- ↑ Melville , R.V. and Freshney, R.C. 1982 British Regional Geology: the Hampshire Basin and adjoining areas 4th edn Institute of Geological Sciences p125 ISBN 011884203X

- ↑ Whitten, D.G.A. and Brooks, J.R.V. 1972 The Penguin Dictionary of Geology ISBN 0140510494

- ↑ Melville , R.V. and Freshney, R.C. 1982 British Regional Geology: the Hampshire Basin and adjoining areas 4th edn Institute of Geological Sciences p125 ISBN 011884203X

- ↑ De la Beche,H.T. 1839 “Report on the Geology of Cornwall, Devon and west Somerset” Memoirs of the Geological Survey, London p.434

- ↑ Proceedings of the Geol. Society of London, Vol.ii. p.577 ( Nov.15, 1837)