The three models of deafness are rooted in either social or biological sciences. These are the cultural model, the social model, and themedicalmodel. The model through which the deaf person is viewed can impact how they are treated as well as their own self perception. In the cultural model, the Deaf belong to a culture in which they are neither infirm nor disabled, but rather have their own fully grammatical and natural language. In the medical model, deafness is viewed undesirable, and it is to the advantage of the individual as well as society as a whole to "cure" this condition. The social model seeks to explain difficulties experienced by deaf individuals that are due to their environment.

A cochlear implant (CI) is a surgically implanted neuroprosthesis that provides a person who has moderate-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss with sound perception. With the help of therapy, cochlear implants may allow for improved speech understanding in both quiet and noisy environments. A CI bypasses acoustic hearing by direct electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve. Through everyday listening and auditory training, cochlear implants allow both children and adults to learn to interpret those signals as speech and sound.

Deaf culture is the set of social beliefs, behaviors, art, literary traditions, history, values, and shared institutions of communities that are influenced by deafness and which use sign languages as the main means of communication. When used as a cultural label especially within the culture, the word deaf is often written with a capital D and referred to as "big D Deaf" in speech and sign. When used as a label for the audiological condition, it is written with a lower case d. Carl G. Croneberg coined the term "Deaf Culture" and he was the first to discuss analogies between Deaf and hearing cultures in his appendices C/D of the 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language.

Heather Leigh Whitestone McCallum is a former beauty queen and conservative activist who was the first deaf Miss America title holder, having lost most of her hearing at 18 months.

Oralism is the education of deaf students through oral language by using lip reading, speech, and mimicking the mouth shapes and breathing patterns of speech. Oralism came into popular use in the United States around the late 1860s. In 1867, the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts, was the first school to start teaching in this manner. Oralism and its contrast, manualism, manifest differently in deaf education and are a source of controversy for involved communities. Oralism should not be confused with Listening and Spoken Language, a technique for teaching deaf children that emphasizes the child's perception of auditory signals from hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Unilateral hearing loss (UHL) is a type of hearing impairment where there is normal hearing in one ear and impaired hearing in the other ear.

Audism as described by deaf activists is a form of discrimination directed against deaf people, which may include those diagnosed as deaf from birth, or otherwise. Tom L. Humphries coined the term in his doctoral dissertation in 1975, but it did not start to catch on until Harlan Lane used it in his writing. Humphries originally applied audism to individual attitudes and practices; whereas Lane broadened the term to include oppression of deaf people.

Graeme Milbourne Clark AC is an Australian Professor of Otolaryngology at the University of Melbourne. His work in ENT surgery, electronics and speech science contributed towards the development of the multiple-channel cochlear implant. His invention was later produced and sold by Cochlear Limited.

Clarke Schools for Hearing and Speech is a national nonprofit organization that specializes in educating children who are deaf or hard of hearing using listening and spoken language (oralism) through the assistance of hearing technology such as hearing aids and cochlear implants. Clarke's five campuses serve more than 1,000 students annually in Canton, Massachusetts, Jacksonville, Florida, New York City, Northampton, Massachusetts, and Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Clarke is the first and largest organization of its kind in the U.S. Its Northampton campus was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2022.

Sound and Fury is a documentary film released in 2000 about two American families with young deaf children and their conflict over whether or not to give their children cochlear implants, surgically implanted devices that may improve their ability to hear but may threaten their Deaf identity.

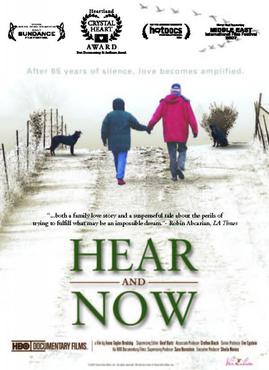

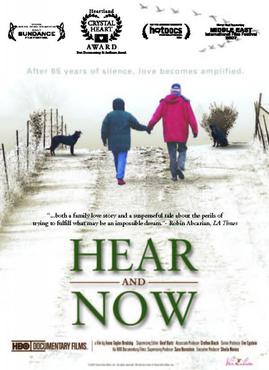

Hear and Now is a 2007 documentary film by Irene Taylor Brodsky, winning awards in 2007 at the Sundance Film Festival and the Heartland Film Festival; and garnering a Peabody Award in 2008.

Auditory-verbal therapy is a method for teaching deaf children to listen and speak using their hearing technology. Auditory-verbal therapy emphasizes listening and seeks to promote the development of the auditory brain to facilitate learning to communicate through talking. It is based on the child’s use of optimally fitted hearing technology.

Prelingual deafness refers to deafness that occurs before learning speech or language. Speech and language typically begin to develop very early with infants saying their first words by age one. Therefore, prelingual deafness is considered to occur before the age of one, where a baby is either born deaf or loses hearing before the age of one. This hearing loss may occur for a variety of reasons and impacts cognitive, social, and language development.

Language acquisition is a natural process in which infants and children develop proficiency in the first language or languages that they are exposed to. The process of language acquisition is varied among deaf children. Deaf children born to deaf parents are typically exposed to a sign language at birth and their language acquisition follows a typical developmental timeline. However, at least 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents who use a spoken language at home. Hearing loss prevents many deaf children from hearing spoken language to the degree necessary for language acquisition. For many deaf children, language acquisition is delayed until the time that they are exposed to a sign language or until they begin using amplification devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. Deaf children who experience delayed language acquisition, sometimes called language deprivation, are at risk for lower language and cognitive outcomes. However, profoundly deaf children who receive cochlear implants and auditory habilitation early in life often achieve expressive and receptive language skills within the norms of their hearing peers; age at implantation is strongly and positively correlated with speech recognition ability. Early access to language through signed language or technology have both been shown to prepare children who are deaf to achieve fluency in literacy skills.

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is written with a lower case d. It later came to be used in a cultural context to refer to those who primarily communicate through sign language regardless of hearing ability, often capitalized as Deaf and referred to as "big D Deaf" in speech and sign. The two definitions overlap but are not identical, as hearing loss includes cases that are not severe enough to impact spoken language comprehension, while cultural Deafness includes hearing people who use sign language, such as children of deaf adults.

The Deaf rights movement encompasses a series of social movements within the disability rights and cultural diversity movements that encourages deaf and hard of hearing to push society to adopt a position of equal respect for them. Acknowledging that those who were Deaf or hard of hearing had rights to obtain the same things as those hearing lead this movement. Establishing an educational system to teach those with Deafness was one of the first accomplishments of this movement. Sign language, as well as cochlear implants, has also had an extensive impact on the Deaf community. These have all been aspects that have paved the way for those with Deafness, which began with the Deaf Rights movement.

Language exposure for children is the act of making language readily available and accessible during the critical period for language acquisition. Deaf and hard of hearing children, when compared to their hearing peers, tend to face more hardships when it comes to ensuring that they will receive accessible language during their formative years. Therefore, deaf and hard of hearing children are more likely to have language deprivation which causes cognitive delays. Early exposure to language enables the brain to fully develop cognitive and linguistic skills as well as language fluency and comprehension later in life. Hearing parents of deaf and hard of hearing children face unique barriers when it comes to providing language exposure for their children. Yet, there is a lot of research, advice, and services available to those parents of deaf and hard of hearing children who may not know how to start in providing language.

Treatment depends on the specific cause if known as well as the extent, type, and configuration of the hearing loss. Most hearing loss results from age and noise, is progressive, and irreversible. There are currently no approved or recommended treatments to restore hearing; it is commonly managed through using hearing aids. A few specific types of hearing loss are amenable to surgical treatment. In other cases, treatment involves addressing underlying pathologies, but any hearing loss incurred may be permanent.

Debara Lyn Tucci is an American otolaryngologist, studying ear, nose, and throat conditions. She co-founded the Duke Hearing Center and currently serves as a professor of Surgery and Director of the Cochlear Implant Program at Duke University. In September 2019 she became Director of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, one of the National Institutes of Health's 27 Institutes and Centers.

In Ireland, 8% of adults are affected by deafness or severe hearing loss. In other words, 300,000 Irish require supports due to their hearing loss.