Related Research Articles

The Chalcolithic was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in different areas, but was absent in some parts of the world, such as Russia, where there was no well-defined Copper Age between the Stone and Bronze Ages. Stone tools were still predominantly used during this period.

Tiwanaku is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, near Lake Titicaca, about 70 kilometers from La Paz, and it is one of the largest sites in South America. Surface remains currently cover around 4 square kilometers and include decorated ceramics, monumental structures, and megalithic blocks. It has been conservatively estimated that the site was inhabited by 10,000 to 20,000 people in AD 800.

The Inca road system was the most extensive and advanced transportation system in pre-Columbian South America. It was about 40,000 kilometres (25,000 mi) long. The construction of the roads required a large expenditure of time and effort.

Dumbarton Oaks, formally the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, is a historic estate in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was the residence and gardens of wealthy U.S. diplomat Robert Woods Bliss and his wife Mildred Barnes Bliss. The estate was founded by the Bliss couple, who gave the home and gardens to Harvard University in 1940.

The Wari were a Middle Horizon civilization that flourished in the south-central Andes and coastal area of modern-day Peru, from about 500 to 1000 AD.

Chimor was the political grouping of the Chimú culture. The culture arose about 900 CE, succeeding the Moche culture, and was later conquered by the Inca emperor Topa Inca Yupanqui around 1470, fifty years before the arrival of the Spanish in the region. Chimor was the largest kingdom in the Late Intermediate Period, encompassing 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) of coastline.

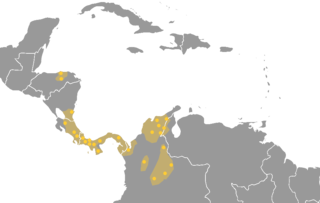

The Intermediate Area is an archaeological geographical area of the Americas that was defined in its clearest form by Gordon R. Willey in his 1971 book An Introduction to American Archaeology, Vol. 2: South America. It comprises the geographical region between Mesoamerica to the north and the Central Andes to the south, including portions of Honduras and Nicaragua and most of the territory of the republics of Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia. As an archaeological concept, the Intermediate Area has always been somewhat poorly defined.

Inca architecture is the most significant pre-Columbian architecture in South America. The Incas inherited an architectural legacy from Tiwanaku, founded in the 2nd century B.C.E. in present-day Bolivia. A core characteristic of the architectural style was to use the topography and existing materials of the land as part of the design. The capital of the Inca empire, Cuzco, still contains many fine examples of Inca architecture, although many walls of Inca masonry have been incorporated into Spanish Colonial structures. The famous royal estate of Machu Picchu is a surviving example of Inca architecture. Other significant sites include Sacsayhuamán and Ollantaytambo. The Incas also developed an extensive road system spanning most of the western length of the continent and placed their distinctive architecture along the way, thereby visually asserting their imperial rule along the frontier.

The Inca society was the society of the Inca civilization in Peru. The Inca Empire, which lasted from 1438 to 1533 A.D., represented the height of this civilization. The Inca state was known as the Kingdom of Cusco before 1438. Over the course of the empire, the rulers used conquest and peaceful assimilation to incorporate a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andes mountain ranges. The empire proved relatively short-lived however: by 1533, Atahualpa, the last Sapa Inca (emperor) of the Inca Empire, was killed on the orders of the conquistador Francisco Pizarro, marking the beginning of Spanish rule. The last Inca stronghold, the Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba, was conquered by the Spanish in 1572.

The chakana is a stepped cross motif used by the Inca and pre-incan Andean societies. The most commonly used variation of this symbol today is made up of an equal-armed cross indicating the cardinal points of the compass and a superimposed square. Chakana means 'bridge', and means 'to cross over' in Quechua. The Andean cross motif appears in pre-contact artifacts such as textiles and ceramics from such cultures as the Chavín, Wari, Chancay, and Tiwanaku, but with no particular emphasis and no key or guide to a means of interpretation. The anthropologist Alan Kolata calls the Andean cross "one of the most ubiquitous, if least understood elements in Tiwanaku iconography". The Andean cross symbol has a long cultural tradition spanning 4,000 years up to the Inca Empire.

Arsenical bronze is an alloy in which arsenic, as opposed to or in addition to tin or other constituent metals, is combined with copper to make bronze. The use of arsenic with copper, either as the secondary constituent or with another component such as tin, results in a stronger final product and better casting behavior.

Pumapunku or Puma Punku is a 6th-century T-shaped and strategically aligned man-made terraced platform mound with a sunken court and monumental structure on top. It is part of the Pumapunku complex, at the Tiwanaku Site near Tiwanacu, in western Bolivia. The Pumapunku complex is a collection of plazas and ramps centered on the Pumapunku platform mound. Today only the ruins of the monumental complex on top of the Puma Punku platform mound remain.

The Andean textile tradition once spanned from the Pre-Columbian to the Colonial era throughout the western coast of South America, but was mainly concentrated in what is now Peru. The arid desert conditions along the coast of Peru have allowed for the preservation of these dyed textiles, which can date to 6000 years old. Many of the surviving textile samples were from funerary bundles, however, these textiles also encompassed a variety of functions. These functions included the use of woven textiles for ceremonial clothing or cloth armor as well as knotted fibers for record-keeping. The textile arts were instrumental in political negotiations, and were used as diplomatic tools that were exchanged between groups. Textiles were also used to communicate wealth, social status, and regional affiliation with others. The cultural emphasis on the textile arts was often based on the believed spiritual and metaphysical qualities of the origins of materials used, as well as cosmological and symbolic messages within the visual appearance of the textiles. Traditionally, the thread used for textiles was spun from indigenous cotton plants, as well as alpaca and llama wool.

Elizabeth P. Benson was an American art historian, curator and scholar, known for her extensive contributions over a long career to the study of pre-Columbian art, in particular that of Mesoamerica and the Andes. A former "Andrew S. Keck Distinguished Visiting Professor of Art History" at the American University in Washington, D.C., Benson had also a long association with the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, where she served both as director of Pre-Columbian studies and as curator of the institution's collection of Pre-Columbian artworks. Benson was born in May 1924 and died in Washington D.C. in March 2018 at the age of 93.

Metallurgy in pre-Columbian America is the extraction, purification and alloying of metals and metal crafting by Indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European contact in the late 15th century. Indigenous Americans had been using native metals from ancient times, with recent finds of gold artifacts in the Andean region dated to 2155–1936 BC, and North American copper finds being dated to approximately 5000 BC. The metal would have been found in nature without the need for smelting, and shaped into the desired form using hot and cold hammering without chemical alteration or alloying. As of 1999, "no one has found evidence that points to the use of melting, smelting and casting in prehistoric eastern North America."

The Andean civilizations were South American complex societies of many indigenous people. They stretched down the spine of the Andes for 4,000 km from southern Colombia, to Ecuador and Peru, including the deserts of coastal Peru, to north Chile and northwest Argentina. Archaeologists believe that Andean civilizations first developed on the narrow coastal plain of the Pacific Ocean. The Caral or Norte Chico civilization of coastal Peru is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, dating back to 3500 BCE. Andean civilizations are one of at least five civilizations in the world deemed by scholars to be "pristine." The concept of a "pristine" civilization refers to a civilization that has developed independently of external influences and is not a derivative of other civilizations.

The Diquis culture was a pre-Columbian indigenous culture of Costa Rica that flourished from AD 700 to 1530. The word "diquís" means "great waters" or "great river" in the Boruca language. The Diquis formed part of the Greater Chiriqui culture that spanned from southern Costa Rica to western Panama.

Axe-monies refer to bronze artifacts found in both western Mesoamerica and the northern Andes. Based on ethnohistorical, archaeological, chemical, and metallurgical analyses, the scholars Hosler, Lechtman and Holm have argued for their use in both regions through trade. In contrast to naipes, bow-tie- or card-shaped metal objects which appear in the archaeological record only in the northern Andean coastal region, axe-monies are found in both Mesoamerican and Andean cultural zones. More specifically, it is argued that the system of money first arose on the north coast of Peru and Ecuador in the early second millennium CE. In both regions, bronze was smelted, likely by family units, and hammered into thin, axe-shaped forms and bundled in multiples of five, usually twenty. As they are often found in burials, it is likely that in addition to their presumed economic use, they also had ceremonial value.

The Tiwanaku Polity was a Pre-Columbian polity in western Bolivia based in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Tiwanaku was one of the most significant Andean civilizations. Its influence extended into present-day Peru and Chile and lasted from around 600 to 1000 AD. Its capital was the monumental city of Tiwanaku, located at the center of the polity's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. This area has clear evidence for large-scale agricultural production on raised fields that probably supported the urban population of the capital. Researchers debate whether these fields were administered by a bureaucratic state (top-down) or through a federation of communities with local autonomy. Tiwanaku was once thought to be an expansive military empire, based mostly on comparisons to the later Inca Empire. However, recent research suggests that labelling Tiwanaku as an empire or even a state may be misleading. Tiwanaku is missing a number of features traditionally used to define archaic states and empires: there is no defensive architecture at any Tiwanaku site or changes in weapon technology, there are no princely burials or other evidence of a ruling dynasty or a formal social hierarchy, no evidence of state-maintained roads or outposts, and no markets.

The economy of the Inca Empire, which lasted from 1438 to 1532, was based on local traditions of "solidarity" and "mutualism", transported to an imperial scale, and established an economic structure that allowed for substantial agricultural production as well as the exchange of products between communities. It was based on the institution of reciprocity, considered the socioeconomic and political system of the Pre-Columbian Andes.

References

- ↑ "DMSE - Faculty - Heather N. Lechtman". Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ↑ "CMRAE - Heather N. Lechtman".

- ↑ "Heather Nan Lechtman". MacArthur Foundation. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- ↑ "Heather Nan Lechtman". MIT Department of Materials Science and Engineering. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- ↑ "Senior Fellows, Pre-Columbian Studies, Dumbarton Oaks". Archived from the original on 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ JOHN NOBLE WILFORD (May 8, 2007). "How the Inca Leapt Canyons". The New York Times.