Related Research Articles

Rhodesia, officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979. During this fourteen-year period, Rhodesia served as the de facto successor state to the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, and in 1980 it became modern day Zimbabwe.

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked, self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South Zambesia until annexation by Britain, at the behest of Cecil Rhodes's British South Africa Company. The bounding territories were Bechuanaland (Botswana), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Portuguese Mozambique (Mozambique) and the Transvaal Republic.

Witness Pasichigare Magunda Mangwende was a Zimbabwean politician who served as head of several government ministries in the Mugabe administration, diplomat, and as provincial governor for Harare.

White Zimbabweans, also known as Rhodesians are Zimbabwean people of European descend. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, these Zimbabweans of European ethnic origin are mostly English-speaking descendants of British settlers. A small minority are either Afrikaans-speaking descendants of Afrikaners from South Africa or those descended from Greek, Portuguese, Italian, and Jewish immigrants.

Goffals or Coloured Zimbabweans are persons of mixed race, predominately those claiming both European and African descent, in Malawi, Zambia, and, particularly Zimbabwe. They are generally known as Coloureds, though the term Goffal is used by some in the Coloured community to refer to themselves, though this does not refer to the mixed-race community in nearby South Africa. The community includes many diverse constituents of Shona, Northern Ndebele, Bemba, Fengu, British, Afrikaner, Cape Coloured, Cape Malay and less commonly Portuguese, Greek, Goan, and Indian descent. Similar mixed-race communities exist throughout Southern Africa, notably the Cape Coloureds of South Africa.

Bernard Mizeki was an African Christian missionary and martyr. Born in Mozambique, he moved to Cape Town, attended an Anglican school, and became a Christian.

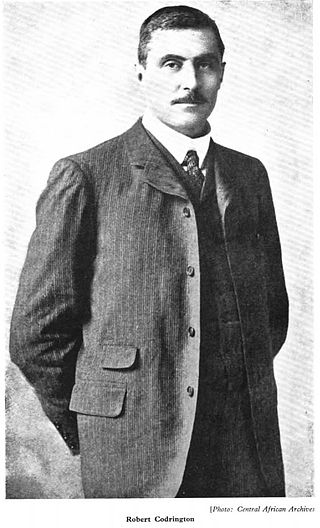

Robert Edward Codrington was the colonial Administrator of the two territories ruled by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) which became present-day Zambia. He was Administrator of North-Eastern Rhodesia, based at Fort Jameson, now Chipata, from 11 July 1898 to 24 April 1907, and then of North-Western Rhodesia, based at Livingstone from February 1908 to his death in London on 16 December 1908 from heart disease at age 39. He laid the foundation for the amalgamation of the two territories as Northern Rhodesia four years later.

The Black Peril refers to the fear of colonial settlers that black men are attracted to white women and are having sexual relations with them. This may go back to class and race prejudices, Examples of class and racial prejudice can be seen in British colonialism of India and Africa. One of the major areas that has been written and documented in having experienced the Black Peril is South Africa, or more specifically in certain writings, Southern Rhodesia, which later became the modern-day country Zimbabwe in 1980. Black Peril is a colonial based fear that started in Southern Rhodesia and survived all the way to the independence of Zimbabwe.

The colonial history of Southern Rhodesia is considered to be a time period from the British government's establishment of the government of Southern Rhodesia on 1 October 1923, to Prime Minister Ian Smith's unilateral declaration of independence in 1965. The territory of 'Southern Rhodesia' was originally referred to as 'South Zambezia' but the name 'Rhodesia' came into use in 1895. The designation 'Southern' was adopted in 1901 and dropped from normal usage in 1964 on the break-up of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and Rhodesia became the name of the country until the creation of Zimbabwe Rhodesia in 1979. Legally, from the British perspective, the name Southern Rhodesia continued to be used until 18 April 1980, when the name Republic of Zimbabwe was formally proclaimed.

Many languages are spoken, or historically have been spoken, in Zimbabwe. Since the adoption of its 2013 Constitution, Zimbabwe has 16 official languages, namely Chewa, Chibarwe, English, Kalanga, Koisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda, Xhosa. The country's main languages are Shona, spoken by over 70% of the population, and Ndebele, spoken by roughly 20%. English is the country's lingua franca, used in government and business and as the main medium of instruction in schools. English is the first language of most white Zimbabweans, and is the second language of a majority of black Zimbabweans. Historically, a minority of white Zimbabweans spoke Afrikaans, Greek, Italian, Polish, and Portuguese, among other languages, while Gujarati and Hindi could be found amongst the country's Indian population. Deaf Zimbabweans commonly use one of several varieties of Zimbabwean Sign Language, with some using American Sign Language. Zimbabwean language data is based on estimates, as Zimbabwe has never conducted a census that enumerated people by language.

White Africans of European ancestry refers to citizens or residents in Africa who can trace full or partial ancestry to Europe. They are distinguished from indigenous North African people who are sometimes identified as white but not European. In 1989, there were an estimated 4.6 million white people with European ancestry on the African continent.

The Indian presence in what is now Zimbabwe dates back to 1890 or earlier. Some scholars have suggested the similarities of the gold mining techniques carried out in southern Zimbabwe during ancient periods with the Indian ones, a brass cup of Hindu workmanship dated to 14th or 15th century AD has been found in Zimbabwean workings. During colonial period Indian plantation workers in South Africa crossed the border into Southern Rhodesia. A voluntary wave of Indian migrants also came at this time from the east, made up mostly of Gujarati men crossing the Indian Ocean to look for new opportunities. These men landed in Beira in Mozambique. Finding that immigration restrictions made it difficult for them to go to South Africa, they made their way across Mozambique, ending up what was then Southern Rhodesia. Further immigration was restricted in 1924 when the colony became a self-governing colony of the United Kingdom. The next year, entry of Indian migrants was restricted to wives and minor children of existing residents, with exceptions made on occasion for teachers and priests.

The Southern Rhodesia Communist Party was an illegal, underground communist party established in Southern Rhodesia which was formed in large part due to the minority settler rule, which had an immensely repressive structure. It emerged in 1941 from a split in the Rhodesia Labour Party. The party consisted of a small, and predominantly white, membership. During the parties existence it had links to other communist parties such as the Communist Party of South Africa and the Communist Party of Great Britain. The party disappeared in the late 1940s, with the exact date of its dissolution not being known. Nobel Laureate Doris Lessing author of various works including “The Grass is Singing,” is the most well known member of the Southern Rhodesian Communist Party.

Racism in Zimbabwe was introduced during the colonial era in the 19th century, when emigrating white settlers began racially discriminating against the indigenous Africans living in the region. The colony of Southern Rhodesia and state of Rhodesia were both dominated by a white minority, which imposed racist policies in all spheres of public life. In the 1960s–70s, African national liberation groups waged an armed struggle against the white Rhodesian government, culminating in a peace accord that brought the ZANU–PF to power but which left much of the white settler population's economic authority intact.

Martha Quest (1952) is the second novel of British Nobel Prize in Literature-winner Doris Lessing, and the first of the five-volume semi-autobiographical Children of Violence series, which traces Martha Quest’s life to middle age. The other volumes in The Children of Violence are A Proper Marriage (1954), A Ripple from the Storm (1958), Landlocked (1965), and The Four-Gated City (1969).

Mangwende is a dynasty from Southern Africa, Zimbabwe commonly known as Mangwende dynasty of Nhowe or Mangwende of Nhowe. It is the royal dynasty of the Nhowe people, who are a part of the Shona tribe now living in Murewa, Mashonaland East, Zimbabwe. The Mangwende dynasty was started by the patriarch of the Nhowe people, Sakubvunza in 1606 who established the Shona traditional state of Nhowe. The name Nhowe refers to the traditional state as well as the Nhowe people.

Native American outing programs were associated with American Indian boarding schools in the United States. These were operated both on and off reservations, primarily from the late 19th century to World War II. Students from boarding schools were assigned to live with and work for European-American families, often during summers, ostensibly to learn more about English language, useful skills, and majority culture, but in reality, primarily as a source of unpaid labor. Many boarding schools continued operating into the 1960s and 1970s.

Jane Ngwenya was a Zimbabwean politician.

Zimbabwean nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Zimbabwe, as amended; the Citizenship of Zimbabwe Act, and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a Zimbabwean national. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Commonwealth countries often use the terms nationality and citizenship as synonyms, despite their legal distinction and the fact that they are regulated by different governmental administrative bodies. Zimbabwean nationality is typically obtained under the principal of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Zimbabwean nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through registration, a process known elsewhere as naturalisation.

Stella Madzimbamuto was a South African-born Zimbabwean nurse and plaintiff in the landmark legal case of Madzimbamuto v Lardner-Burke. Born as Stella Nkolombe in District Six of Cape Town in 1930, she trained as a nurse at South Africa's first hospital to treat black Africans, earning a general nursing and a midwifery certification. After working for three years at Ladysmith Provincial Hospital, she married a Southern Rhodesian and relocated. From 1956 to 1959, she worked as a general nurse at the Harare Central Hospital. In 1959, her husband, Daniel Madzimbamuto, was detained as a political prisoner. He would remain in detention until 1974, while she financially supported the family.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Tawse-Jollie, Ethel (1927). "Southern Rhodesia: A White Man's Country in the Tropics". Geographical Review. 17 (1): 89–106. Bibcode:1927GeoRv..17...89T. doi:10.2307/208135. JSTOR 208135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kaler, Amy (1999). "Visions of Domesticity in the African Women's Homecraft Movement in Rhodesia". Social Science History. 23 (3): 269–309. doi:10.1017/s0145553200018101. PMID 22416325.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Peet, Stephen (Director); Mangwende, Mai (Writer) (1949). The Wives of Nendi (Film short). tt4433416 at IMDb .

- ↑ Huff, Barbara Jean (1996). Christian women's organizations in Zimbabwe : facilitating women's participation in development through advocacy and education (Thesis). University of Massachusetts Amherst. p. 161. doi: 10.7275/m635-qa37 . OCLC 982385201.

- 1 2 Barnes, Teresa Ann (2002). "Virgin Territory?: Travel and Migration by African Women in Twentieth-Century Southern Africa". In Geiger, Susan; Allman, Jean; Musisi, Nakanyike (eds.). Women in African Colonial Histories. Indiana University Press. pp. 164–190. hdl:2027/heb04111.0001.001. ISBN 978-0-253-21507-9. OCLC 1205417717.

- 1 2 Huff, Barbara Jean (1996). Christian women's organizations in Zimbabwe : facilitating women's participation in development through advocacy and education (Thesis). University of Massachusetts Amherst. p. 163. doi: 10.7275/m635-qa37 . OCLC 982385201.

- 1 2 Law, Kate (2010). "Making Marmalade and Imperial Mentalities: the case of a Colonial wife". African Research & Documentation. 113: 19–25. doi:10.1017/S0305862X00019592. ProQuest 847687649.

- 1 2 3 Musisi, Nakanyike B. (1992). "Colonial and Missionary Education: Women and Domesticity in Uganda, 1900-1945". African Encounters with Domesticity. pp. 172–194. doi:10.36019/9780813571119-010. ISBN 978-0-8135-7111-9.