Related Research Articles

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, art name Chōkōdō Shujin (澄江堂主人), was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him. He took his own life at the age of 35 through an overdose of barbital.

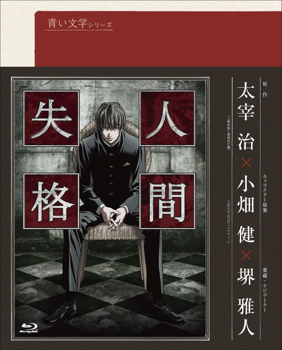

Shūji Tsushima, known by his pen name Osamu Dazai, was a Japanese novelist and author. A number of his most popular works, such as The Setting Sun and No Longer Human, are considered modern-day classics.

Rashomon is a 1950 Japanese jidaigeki film directed by Akira Kurosawa from a screenplay he co-wrote with Shinobu Hashimoto. Starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyō, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura, it follows various people who describe how a samurai was murdered in a forest. The plot and characters are based upon Ryūnosuke Akutagawa's short story "In a Grove", with the title and framing story taken from Akutagawa's "Rashōmon". Every element is largely identical, from the murdered samurai speaking through a Shinto psychic to the bandit in the forest, the monk, the assault of the wife, and the dishonest retelling of the events in which everyone shows their ideal self by lying.

Rashōmon (羅生門) is a short story by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa based on tales from the Konjaku Monogatarishū.

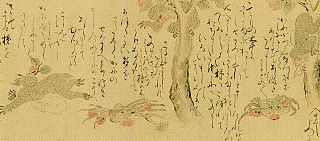

Konjaku Monogatarishū, also known as the Konjaku Monogatari (今昔物語), is a Japanese collection of over one thousand tales written during the late Heian period (794–1185). The entire collection was originally contained in 31 volumes, of which 28 remain today. The volumes cover various tales from India, China and Japan. Detailed evidence of lost monogatari exist in the form of literary critique, which can be studied to reconstruct the objects of their critique to some extent.

In a Grove, also translated as In a Bamboo Grove, is a Japanese short story by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa first published in 1922. It was ranked as one of the "10 best Asian novels of all time" by The Telegraph in 2014. In a Grove has been adapted several times, most notably by Akira Kurosawa for his award-winning 1950 film Rashōmon.

Masao Kume was a Japanese popular playwright, novelist and haiku poet active during the late Taishō and early Shōwa periods of Japan. His wife and the wife of Nagai Tatsuo were sisters, making them brothers-in-law.

Fumiko Enchi was the pen-name of Fumiko Ueda, one of the most prominent Japanese women writers in the Shōwa period of Japan. As a writer, Enchi is best known for her explorations into the ideas of sexuality, gender, human identity, and spirituality.

Jay Rubin is an American translator, writer, scholar and Japanologist. He is one of the main translators of the works of the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami into English. He has also written a guide to Japanese, Making Sense of Japanese, and a biographical literary analysis of Murakami.

Portrait of Hell, also titled A Story of Hell and The Hell Screen, is a 1969 Japanese jidaigeki film directed by Shirō Toyoda starring Tatsuya Nakadai and Kinnosuke Nakamura. The film is based on the short story Hell Screen by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa.

Musashi Gundoh is a Japanese anime television series, based on an unused story by Monkey Punch. It premiered in Japan on the satellite station BS-i on April 9, 2006, and was also set to be broadcast across Japan by the anime satellite television network Animax from October 2006. It is also legally distributed over the Internet by GyaO from May 13, 2006. According to the producer, there were originally plans to broadcast the anime overseas, but they were scrapped due to poor reception of the anime.

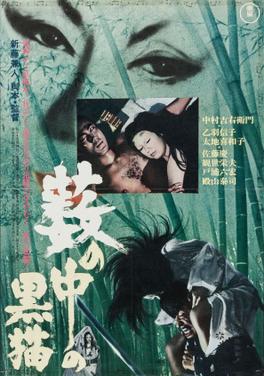

Kuroneko is a 1968 Japanese historical drama and horror film directed by Kaneto Shindō, and an adaptation of a supernatural folktale. Set during a civil war in feudal Japan, the film's plot concerns the vengeful spirits, or onryō, of a woman and her daughter-in-law, who died at the hands of a band of samurai. It stars Kichiemon Nakamura, Nobuko Otowa, and Kiwako Taichi.

The Crab and the Monkey, also known as Monkey-Crab Battle or The Quarrel of the Monkey and the Crab, is a Japanese folktale. In the story, a sly monkey kills a crab, and is later killed in revenge by the crab's offspring. Retributive justice is the main theme of the story.

The Spider's Thread is a 1918 short story by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, first published in the children's magazine Akai Tori.

Dragon: the Old Potter's Tale is a short story by Japanese writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. It was first published in a 1919 collection of Akutagawa short stories, Akutagawa Ryūnosuke zenshū. The story is based on a thirteenth-century Japanese tale, with Akutagawa's Taishō literary interpretations of modern psychology and the nature of religion.

The Nose is a satirical short story by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa based on a thirteenth-century Japanese tale from the Uji Shūi Monogatari. "The Nose" was Akutagawa's second short story, written not long after "Rashōmon". It was first published in January 1916 in the Tokyo Imperial University student magazine Shinshichō and later published in other magazines and various Akutagawa anthologies. The story is mainly a commentary on vanity and religion, in a style and theme typical to Akutagawa's work.

Aoi Bungaku Series is a twelve episode Japanese anime series featuring adaptations inspired by six short stories from Japanese literature. The six stories are adapted from classic Japanese tales. Happinet, Hakuhodo DY Media Partners, McRAY, MTI, Threelight Holdings, Movic, and Visionare were involved in the production of the series. Character designs were provided by manga artists Takeshi Obata, Tite Kubo and Takeshi Konomi (#9–10). The stories adapted here may stray away significantly from the original plot of the classics, even if they try to capture the essence of the stories. There are some titbits told by the host Sakai Masato about the background of the story before the animation starts.

"The Moonlit Road" is a gothic horror short story by American Civil War soldier, wit, and writer Ambrose Bierce. It first appeared in a 1907 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, illustrated by Charles B. Falls. This story is presented in three parts and relates the tale of the murder of Julia Hetman from the perspective of her son, a man who may be her husband, and Julia herself, through a medium.

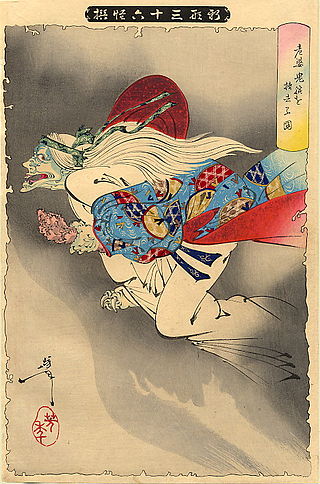

Ibaraki-dōji is an oni featured in tales of the Heian period. In the tales, Ibaraki-dōji is based on Mount Ōe, and once went on a rampage in Kyoto. The "Ibaraki" in his name may refer to Ibaraki, Osaka; "dōji" means "child", but in this context is a demon offspring. Ibaraki-dōji was the most important servant of Shuten-dōji.

Katayama Hiroko was a Japanese poet and translator. She did many translations of Irish writers under the pseudonym Matsumura Mineko. Her husband was a noted bureaucrat. She reportedly took her pseudonym from a name she saw on a child's umbrella. She maintained a friendship with Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and he reportedly said of her "Finally I have met a woman who can be called my equal in the arena of words." She also acted as a mentor to Muraoka Hanako who is known in Japan for translating Anne of Green Gables.

References

- ↑ Rubin, Jay. "Chronology." Rashōmon and 17 Other Stories. By Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. New York: Penguin Group, 2006. xi–xvii.

- ↑ Akutagawa, Ryūnosuke. Akutagawa Ryūnosuke zenshū. Ed. Toshirō Kōno. 24 vols. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1995–8.

- ↑ Akutagawa, Ryūnosuke. Hell Screen and Other Stories. Trans. W.H.H. Norman. Tokyo: Hokuseido, 1948.

- 1 2 Akutagawa Ryūnosuke. "Hell Screen." 1918. Rashōmon and 17 Other Stories. Trans. Jay Rubin. New York City: Penguin Group, 2006. 3–9.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Akutagawa Ryunosuke". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008.

- ↑ Ueda, Makoto. Matsuo Bashō. Twayne's World Authors Series. New York: Twayne, 1970.

- ↑ Benton, Richard P. (1999). "AKUTAGAWA Ryūnosuke". In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Reference Guide to Short Fiction (2nd ed.). St. James Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-55862-222-7.

Hence in this story Akutagawa is asking: How can the objective be distinguished from the subjective? How can the truth be distinguished from fiction?