Tin Pan Alley was a collection of music publishers and songwriters in New York City that dominated the popular music of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It originally referred to a specific place: West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues in the Flower District of Manhattan; a plaque on the sidewalk on 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth commemorates it.

Georgia Gibbs was an American popular singer and vocal entertainer rooted in jazz. Already singing publicly in her early teens, Gibbs achieved acclaim and notoriety in the mid-1950s copying songs originating with the black rhythm and blues community and later became a featured vocalist for many radio and television variety and comedy programs. Her key attribute was tremendous versatility and an uncommon stylistic range from melancholy ballad to uptempo swinging jazz and rock and roll.

Collins & Harlan, the team of American singers Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan, formed a popular comic duo between 1903 and 1926. They sang ragtime standards as well as what were known as "coon songs" – music sung by white performers in a black dialect. Their material also employed many other stereotypes of the time including Irishmen and farmers. Rival recording artist Billy Murray nicknamed them "The Half-Ton Duo" as both men were rather overweight. Collins and Harlan produced many number one hits with recordings of minstrel songs such as "My Gal Irene", "I Know Dat I'll be Happy Til I Die", "Who Do You Love?" and "Down Among the Sugarcane". Their song "That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland", recorded November 8, 1916, is among the first recorded uses of the word "jas" which eventually evolved to "jass", and to the current spelling "jazz".

Arthur Francis Collins was an American baritone who was one of the pioneer recording artists, regarded in his day as "King of the Ragtime Singers".

Byron George Harlan was an American singer from Kansas, a comic minstrel singer and balladeer who often recorded with Arthur Collins. The two together were often billed as "Collins & Harlan".

Charles Kassel Harris was a well regarded American songwriter of popular music. During his long career, he advanced the relatively new genre, publishing more than 300 songs, often deemed by admirers as the "king of the tear jerkers". He is one of the early pioneers of Tin Pan Alley.

J. Fred. Helf was an American composer and sheet music publisher during the early 20th century.

Edgar Leslie was an American songwriter.

"After the Ball" is a popular song written in 1891 by Charles K. Harris. The song is a classic waltz in 3/4 time. In the song, an uncle tells his niece why he has never married. He saw his sweetheart kissing another man at a ball, and he refused to listen to her explanation. Many years later, after the woman had died, he discovered that the man was her brother.

"The Little Lost Child" is a popular song of 1894 by Edward B. Marks and Joseph W. Stern which sold more than two million copies of its sheet music following its promotion as the first ever illustrated song, an early precursor to the music video. The song was also known by its first three words: "A Passing Policeman." The song's success has also been credited to its performance with enthusiasm by Lottie Gilson and Della Fox.

Joseph Edgar Howard was an American Broadway composer, lyricist, librettist, and performer. A famed member of Tin Pan Alley along with wife and composer Ida Emerson as part of the song-writing team of Howard and Emerson, his hits included "Hello! Ma Baby" and Broadway musicals like "I Wonder Who's Kissing Her Now?".

Her Greatest Hits is a 2008 compilation album of songs recorded by American artist Jo Stafford. This album, released by JSP on January 8, 2008, features over 100 of Stafford's recordings.

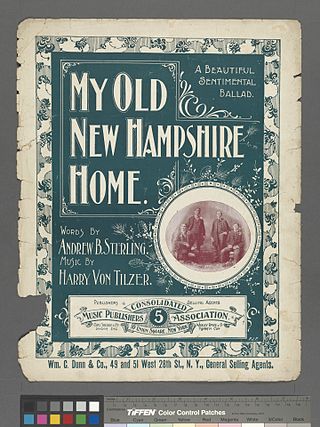

"My Old New Hampshire Home" is an 1898 song that was the first popular hit of composer Harry Von Tilzer, with lyrics by Andrew B. Sterling.

Robert A. King was a prolific early twentieth century American composer, who wrote under pen names including the pen names, Mary Earl, Robert A. Keiser, and Betty Chapin.

"Come Home, Father" is a temperance song written by Henry Clay Work in 1864. According to George Birdseye, a contemporary biographer of the time, the song was the "pioneer and pattern for all the many temperance pieces now in the market, not a few of which are very palpable imitations." Although the sheet music was first published in 1864, the song is believed to have been first performed in 1858 as part of the Broadway play, Ten Nights in a Barroom, an adaptation of the 1854 temperance novel. The song was eventually adopted as the anthem of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.