Related Research Articles

Henry Louis Mencken was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, and contemporary movements. His satirical reporting on the Scopes Trial, which he dubbed the "Monkey Trial", also gained him attention. The term Menckenian has entered multiple dictionaries to describe anything of or pertaining to Mencken, including his combative rhetorical and prose style.

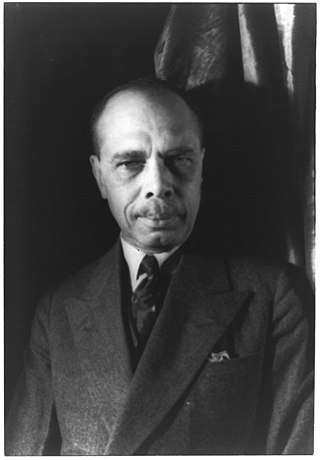

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Pictorialism is an international style and aesthetic movement that dominated photography during the later 19th and early 20th centuries. There is no standard definition of the term, but in general it refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of creating an image rather than simply recording it. Typically, a pictorial photograph appears to lack a sharp focus, is printed in one or more colors other than black-and-white and may have visible brush strokes or other manipulation of the surface. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer's realm of imagination.

James Weldon Johnson was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920, he was chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novel and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of Black culture. He wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing", which later became known as the Black National Anthem, the music being written by his younger brother, composer J. Rosamond Johnson.

During the history of the Latter Day Saint movement, the relationship between Black people and Mormonism has included enslavement, exclusion and inclusion, and official and unofficial discrimination. Black people have been involved with the Latter Day Saint movement since its inception in the 1830s. Their experiences have varied widely, depending on the denomination within Mormonism and the time of their involvement. From the mid-1800s to 1978, Mormonism's largest denomination – the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – barred Black women and men from participating in the ordinances of its temples necessary for the highest level of salvation, prevented most men of Black African descent from being ordained into the church's lay, all-male priesthood, supported racial segregation in its communities and schools, taught that righteous Black people would be made white after death, and opposed interracial marriage. The temple and priesthood racial restrictions were lifted by church leaders in 1978. In 2013, the church disavowed its previous teachings on race for the first time.

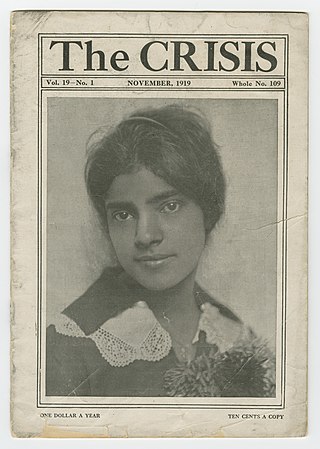

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, William Stanley Braithwaite, and Mary Dunlop Maclean. The Crisis has been in continuous print since 1910, and it is the oldest Black-oriented magazine in the world. Today, The Crisis is "a quarterly journal of civil rights, history, politics and culture and seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues that continue to plague African Americans and other communities of color."

The Dial was an American magazine published intermittently from 1840 to 1929. In its first form, from 1840 to 1844, it served as the chief publication of the Transcendentalists. From the 1880s to 1919 it was revived as a political review and literary criticism magazine. From 1920 to 1929 it was an influential outlet for modernist literature in English. In January 2023, The Dial was revived once again as a magazine of international writing and reporting.

Archibald Henry Grimké was an African-American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He graduated from freedmen's schools, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and Harvard Law School, and served as American Consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. He was an activist for the rights of Black Americans, working in Boston and Washington, D.C. He was a national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as president of its Washington, D.C. chapter.

Mary Burnett Talbert was an American orator, activist, suffragist and reformer. In 2005, Talbert was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

"New Negro" is a term popularized during the Harlem Renaissance implying a more outspoken advocacy of dignity and a refusal to submit quietly to the practices and laws of Jim Crow racial segregation. The term "New Negro" was made popular by Alain LeRoy Locke in his anthology The New Negro.

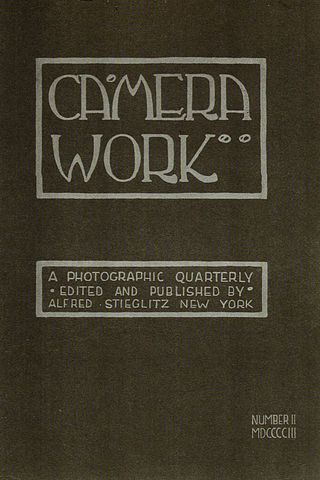

Camera Work was a quarterly photographic journal published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917. It presented high-quality photogravures by some of the most important photographers in the world, with the goal to establish photography as a fine art. It was called "consummately intellectual", "by far the most beautiful of all photographic magazines", and "a portrait of an age [in which] the artistic sensibility of the nineteenth century was transformed into the artistic awareness of the present day."

The Photo-Secession was an early 20th century movement that promoted photography as a fine art in general and photographic pictorialism in particular.

Laura and L. D. Nelson were an African-American mother and son who were lynched on May 25, 1911, near Okemah, Okfuskee County, Oklahoma. They had been seized from their cells in the Okemah county jail the night before by a group of up to 40 white men, reportedly including Charley Guthrie, father of the folk singer Woody Guthrie. The Associated Press reported that Laura was raped. She and L. D. were then hanged from a bridge over the North Canadian River. According to one source, Laura had a baby with her who survived the attack.

The Negro Silent Protest Parade, commonly known as the Silent Parade, was a silent march of about 10,000 African Americans along Fifth Avenue starting at 57th Street in New York City on July 28, 1917. The event was organized by the NAACP, church, and community leaders to protest violence directed towards African Americans, such as recent lynchings in Waco and Memphis. The parade was precipitated by the East St. Louis riots in May and July 1917 where at least 40 black people were killed by white mobs, in part touched off by a labor dispute where blacks were used for strike breaking.

The Associated Negro Press (ANP) was an American news service founded in 1919 in Chicago, Illinois by Claude Albert Barnett. The ANP had correspondents, writers, reporters in all major centers of the black population in the United States of America. It supplied news stories, opinions, columns, feature essays, book and movie reviews, critical and comprehensive coverage of events, personalities, and institutions relevant to black Americans. As the ANP grew into a global network. It supplied the vast majority of black newspapers with twice weekly packets.

Albert Rich Brand was an author and innovator in the recording of bird songs. Herbert J. Seligmann wrote Man and Bird Together: A Portrait of Albert R. Brand about him.

J. Hendrix McLane was an American politician. He ran for governor of South Carolina in the 1882 South Carolina gubernatorial election as a Greenback Labor Party candidate. He belonged to several political parties during his career, and was a reformer for a time in the Republican Party. He advocated for the rights of African Americans. He also campaigned for white agrarian poor of the Southeastern United States.

Georgia O'Keeffe - Torso, also known as Georgia O'Keeffe - Nude, is a black and white photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1918. It is one of the more than 300 photographs that he took of his future wife, the painter Georgia O'Keeffe.

The 1935 New York anti-lynching exhibitions were two separate but consecutive art exhibitions held in early 1935 by two different organizations, both in response to a 1934 bill in the United States Congress that dealt with lynching. The organizations involved were the NAACP and the Artists Union, the latter in conjunction with groups including the John Reed Club, the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, and the International Labor Defense.

Hodge Kirnon was a Montserratian scholar, historian, and literary critic, who also worked as an elevator operator at Alfred Stieglitz' gallery 291. He has been described as "one of the leading lights of the postwar Negro Renaissance" and as Montserrat's first historian.

References

- 1 2 3 "Herbert J. Seligmann". The New York Times. 7 March 1984 – via NYTimes.com.

- 1 2 3 "Herbert J. Seligmann Papers, 1908-1984" (PDF). The New York Public Library, Humanities and Social Sciences Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division. September 1992. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ↑ Lawrence, D. H. (8 August 2002). The Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521006989 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Aptheker, Herbert (1989). The Literary Legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois. Kraus International Publications. ISBN 9780527036935.

- ↑ Lanset, Andy (18 February 2019). "One of the Country's Earliest African-American Radio Programs on WNYC 1929-1930". WNYC. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ↑ Krugler, David F. (8 December 2014). 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316195000 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "MRS. H. J. Seligmann". The New York Times. 24 August 1964.

- ↑ "Herbert J. Seligmann papers". New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts.

- 1 2 Seligmann, Herbert J. (1 March 1920). "The menace of race hatred". Harper's Magazine.

- 1 2 3 4 Lane, D. A. (1 April 1921). "Herbert J. Seligmann, The Negro Faces America". The Journal of Negro History. 6 (2): 256–258. doi:10.2307/2713738. JSTOR 2713738.

- ↑ ""Darkwater" and "The Upward Path"". The Virginia Teacher. Vol. II, no. 2. February 1921. Retrieved 22 May 2024– via James Madison University Scholarly Commons.

- ↑ "The Negro Faces America". Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races. Vol. 19, no. 6. Retrieved 22 May 2024– via Modernist Journals Project.

- ↑ Heer, Jeet (29 January 2015). "The New Republic's Legacy on Race: A historical reflection". The New Republic.

- ↑ Mencken, H. L. (1 December 2000). H.L. Mencken's Smart Set Criticism. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 9780895262318 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Scruggs, Charles (1 December 2019). The Sage in Harlem: H. L. Mencken and the Black Writers of the 1920s. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421431390 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Seligmann, Herbert J. (15 August 1920). "American Atrocities in Haiti?". Maclean's. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ↑ "The Conquest of Haiti by Herbert J. Seligman, July 10, 1920 from Selections from The Nation magazine 1865-1990". www.thirdworldtraveler.com.

- ↑ "Memorandum from Herbert J. Seligmann to N.A.A.C.P. Spingarn Medal Award Committee". NAACP. 18 November 1932 – via University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

- ↑ "Expose of Nazi Race Theories Published in Book by Seligmann, Former J.D.C. Aide". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 26 March 1939.

- ↑ "Herbert J. Seligmann". National Gallery of Art. 1921.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Bridge". Cleveland Museum of Art. 30 October 2018.

- ↑ Mitsel, Mikhail (29 December 2016). "Jewish Life in Eastern Europe Before the Holocaust through the Eyes of the JDC Photographer Herbert J. Seligmann". Revista de Istorie a Evreilor din Romania. 1 (16–17): 386–394 – via www.ceeol.com.

- ↑ "John Marin printed material and drawings, 1929-1955". Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ↑ Santayana, George (29 December 2001). The Letters of George Santayana. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262194662 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the American Historical Association". 1959.

- ↑ Lane, D. A. (1 April 1921). "Herbert J. Seligmann, The Negro Faces America". The Journal of Negro History. 6 (2): 256–258. doi:10.2307/2713738. JSTOR 2713738 – via journals.uchicago.edu (Atypon).

- ↑ "D.H. Lawrence; an American interpretation". HathiTrust.

- ↑ Seligmann, Herbert Jacob (18 June 1939). "Race against man". New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons – via Trove.

- ↑ Seligmann, Herbert Jacob (18 June 1965). "A South Carolina Independent of the 1880's: J. Hendrix McLane" – via Google Books.