Mount Vesuvius is a somma–stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, resulting from the collapse of an earlier, much higher structure.

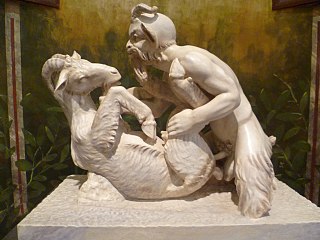

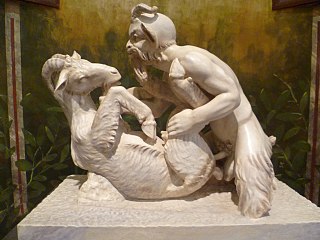

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes.

The Villa of the Papyri was an ancient Roman villa in Herculaneum, in what is now Ercolano, southern Italy. It is named after its unique library of papyri scrolls, discovered in 1750. The Villa was considered to be one of the most luxurious houses in all of Herculaneum and in the Roman world. Its luxury is shown by its exquisite architecture and by the large number of outstanding works of art discovered, including frescoes, bronzes and marble sculpture which constitute the largest collection of Greek and Roman sculptures ever discovered in a single context.

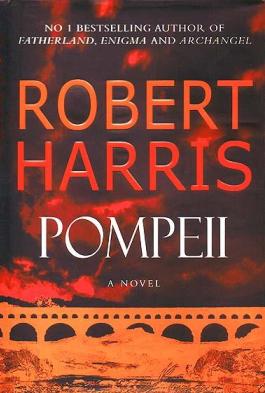

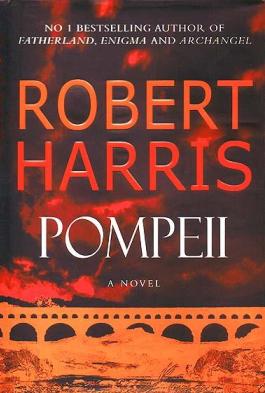

Pompeii is a novel by Robert Harris, published by Random House in 2003. It blends historical fiction with the real-life eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 24 August 79 AD, which overwhelmed the town of Pompeii and its vicinity. The novel is notable for its references to various aspects of volcanology and use of the Roman calendar. In 2007, a film adaptation was planned, to be directed by Roman Polanski with a budget of US$150 million, but was cancelled due to the threat of a looming actors' strike.

Pompeii: The Last Day is a 2003 dramatized documentary that tells of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius towards the end of August 79 CE. This eruption covered the ancient Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in ash and pumice, killing a large number of people trapped between the volcano and the sea. The documentary, which portrays the different phases of the eruption, was directed by Peter Nicholson and written by Edward Canfor-Dumas.

Lucius Caecilius Iucundus was a banker who lived in the Roman town of Pompeii around AD 14–62. His house still stands and can be seen in the ruins of the city of Pompeii which remain after being partially destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The house is known both for its frescoes and for the trove of wax tablets discovered there in 1875, which gave scholars access to the records of Iucundus's banking operations.

Andrew Frederic Wallace-Hadrill, is a British ancient historian, classical archaeologist, and academic. He is Professor of Roman Studies and Director of Research in the Faculty of Classics at the University of Cambridge. He was Director of the British School at Rome between 1995 and 2009, and Master of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge from August 2009 to July 2013.

Ercolano is a town and comune in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania of Southern Italy. It lies at the western foot of Mount Vesuvius, on the Bay of Naples, just southeast of the city of Naples. The medieval town of Resina was built on the volcanic material left by the eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed the ancient city of Herculaneum, from which the present name is derived. Ercolano is a resort and the starting point for excursions to the excavations of Herculaneum and for the ascent of Vesuvius by bus. The town also manufactures leather goods, buttons, glass, and Lacryma Christi wine.

The Villa Poppaea is an ancient luxurious Roman seaside villa located in Torre Annunziata between Naples and Sorrento, in Southern Italy. It is also called the Villa Oplontis or Oplontis Villa A as it was situated in the ancient Roman town of Oplontis.

A lame is a double-sided blade that is used to slash the tops of bread loaves in baking. A lame is used to score bread just before the bread is placed in the oven. Often the blade's cutting edge will be slightly concave-shaped, which allows users to cut flaps considerably thinner than would be possible with a traditional straight razor.

Pompeii and Herculaneum were once thriving towns, 2,000 years ago, in the Bay of Naples. Both cities have rich histories influenced by Greeks, Oscans, Etruscans, Samnites and finally the Romans. They are most renowned for their destruction: both were buried in the AD 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius. For over 1,500 years, these cities were left in remarkable states of preservation underneath volcanic ash, mud and rubble. The eruption obliterated the towns but in doing so, was the cause of their longevity and survival over the centuries.

The ancient Roman city of Pompeii has been frequently featured in literature and popular culture since its modern rediscovery. Pompeii was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Pompeii was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and many surrounding villas, the city was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Herculaneum is an ancient Roman town located in the modern-day comune of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under a massive pyroclastic flow in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Of the many eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, a major stratovolcano in Southern Italy, the best-known is its eruption in 79 AD, which was one of the deadliest in history.

On 5 February AD 62, an earthquake of an estimated magnitude of between 5 and 6 and a maximum intensity of IX or X on the Mercalli scale struck the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, severely damaging them. The earthquake may have been a precursor to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, which destroyed the same two towns. The contemporary philosopher and dramatist Seneca the Younger wrote an account of the earthquake in the sixth book of his Naturales quaestiones, entitled De Terrae Motu.

The House of the Centenary was the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house was discovered in 1879, and was given its modern name to mark the 18th centenary of the disaster. Built in the mid-2nd century BC, it is among the largest houses in the city, with private baths, a nymphaeum, a fish pond (piscina), and two atria. The Centenary underwent a remodeling around 15 AD, at which time the bath complex and swimming pool were added. In the last years before the eruption, several rooms had been extensively redecorated with a number of paintings.

The Garden of the Fugitives is an archaeological site located in the ancient destroyed city of Pompeii, in Regio 1 Insula 21. It contains the casts of 13 victims of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Baking was a popular profession and source of food in ancient Rome. Many ancient Roman baking techniques were developed due to Greek bakers who traveled to Rome following the Third Macedonian War. Ancient Roman bakers could make large quantities of money. This may have contributed to receiving a negative reputation. Bakers used tools such as the fornax, testum, thermospodium, and the clibanus to make bread. Most Roman breads were made using sourdough. The most common way to leaven bread was using flour mixed with grain.