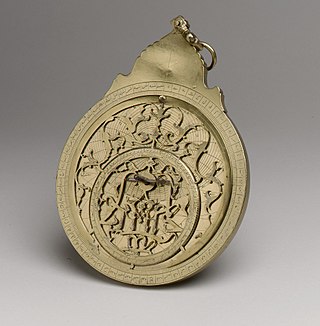

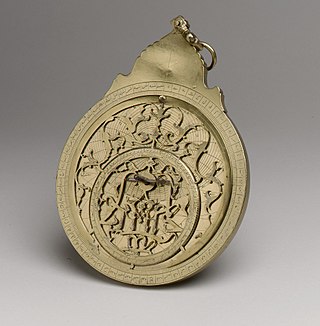

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally 66% copper and 34% zinc. In use since prehistoric times, it is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other within the same crystal structure.

Damascus steel is the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of carbon steel imported from Southern India or made in production centers in Sri Lanka or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water, sometimes in a "ladder" or "rose" pattern. Such blades were reputed to be tough, resistant to shattering, and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.

Yorkshire pudding is a baked pudding made from a batter of eggs, flour, and milk or water. A common British side dish, it is a versatile food that can be served in numerous ways depending on its ingredients, size, and the accompanying components of the meal. As a first course, it can be served with onion gravy. For a main course, it may be served with meat and gravy, and is part of the traditional Sunday roast, but can also be filled with foods such as bangers and mash to make a meal. Sausages can be added to make toad in the hole. In some parts of England, the Yorkshire pudding can be eaten as a dessert, with a sweet sauce called raspberry vinegar. The 18th-century cookery writer Hannah Glasse was the first to use the term "Yorkshire pudding" in print.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is a thermoanalytical technique in which the difference in the amount of heat required to increase the temperature of a sample and reference is measured as a function of temperature. Both the sample and reference are maintained at nearly the same temperature throughout the experiment. Generally, the temperature program for a DSC analysis is designed such that the sample holder temperature increases linearly as a function of time. The reference sample should have a well-defined heat capacity over the range of temperatures to be scanned. Additionally, the reference sample must be stable, of high purity, and must not experience much change across the temperature scan. Typically, reference standards have been metals such as indium, tin, bismuth, and lead, but other standards such as polyethylene and fatty acids have been proposed to study polymers and organic compounds, respectively.

A crucible is a ceramic or metal container in which metals or other substances may be melted or subjected to very high temperatures. Although crucibles have historically tended to be made out of clay, they can be made from any material that withstands temperatures high enough to melt or otherwise alter its contents.

Potato salad is a salad dish made from boiled potatoes, usually containing a dressing and a variety of other ingredients such as boiled eggs and raw vegetables.

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron, iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires, which could not produce temperatures high enough. However, pig iron, having a higher carbon content and thus a lower melting point, could be melted, and by soaking wrought iron or steel in the liquid pig-iron for a long time, the carbon content of the pig iron could be reduced as it slowly diffused into the iron, turning both into steel. Crucible steel of this type was produced in South and Central Asia during the medieval era. This generally produced a very hard steel, but also a composite steel that was inhomogeneous, consisting of a very high-carbon steel and a lower-carbon steel. This often resulted in an intricate pattern when the steel was forged, filed or polished, with possibly the most well-known examples coming from the wootz steel used in Damascus swords. The steel was often much higher in carbon content and in quality in comparison with other methods of steel production of the time because of the use of fluxes. The steel was usually worked very little and at relatively low temperatures to avoid any decarburization, hot short crumbling, or excess diffusion of carbon; just enough hammering to form the shape of a sword. With a carbon content close to that of cast iron, it usually required no heat treatment after shaping other than air cooling to achieve the correct hardness, relying on composition alone. The higher-carbon steel provided a very hard edge, but the lower-carbon steel helped to increase the toughness, helping to decrease the chance of chipping, cracking, or breaking.

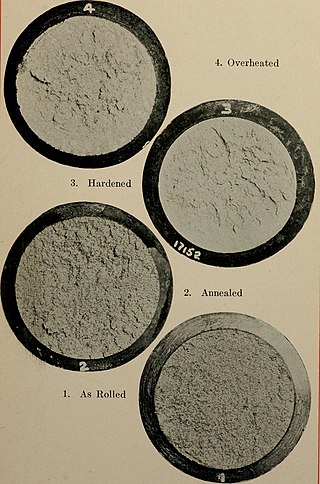

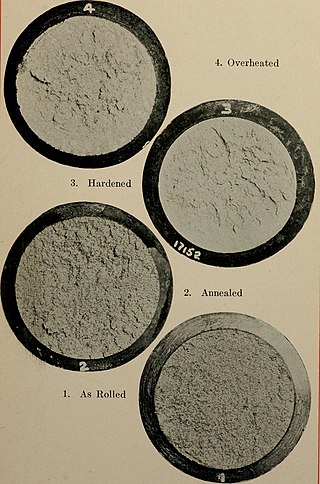

Tool steel is any of various carbon steels and alloy steels that are particularly well-suited to be made into tools and tooling, including cutting tools, dies, hand tools, knives, and others. Their suitability comes from their distinctive hardness, resistance to abrasion and deformation, and their ability to hold a cutting edge at elevated temperatures. As a result, tool steels are suited for use in the shaping of other materials, as for example in cutting, machining, stamping, or forging.

A Hessian is an inhabitant of the German state of Hesse.

Hard-paste porcelain, sometimes called "true porcelain", is a ceramic material that was originally made from a compound of the feldspathic rock petuntse and kaolin fired at a very high temperature, usually around 1400 °C. It was first made in China around the 7th or 8th century and has remained the most common type of Chinese porcelain.

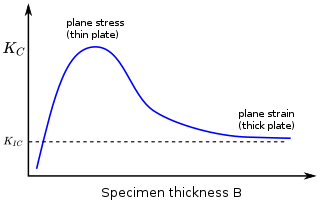

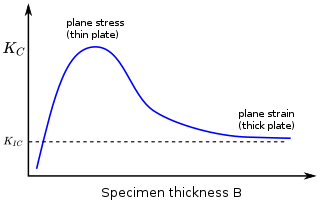

In materials science, fracture toughness is the critical stress intensity factor of a sharp crack where propagation of the crack suddenly becomes rapid and unlimited. A component's thickness affects the constraint conditions at the tip of a crack with thin components having plane stress conditions and thick components having plane strain conditions. Plane strain conditions give the lowest fracture toughness value which is a material property. The critical value of stress intensity factor in mode I loading measured under plane strain conditions is known as the plane strain fracture toughness, denoted . When a test fails to meet the thickness and other test requirements that are in place to ensure plane strain conditions, the fracture toughness value produced is given the designation . Fracture toughness is a quantitative way of expressing a material's resistance to crack propagation and standard values for a given material are generally available.

Aluminum silicate (or aluminium silicate) is a name commonly applied to chemical compounds which are derived from aluminium oxide, Al2O3 and silicon dioxide, SiO2 which may be anhydrous or hydrated, naturally occurring as minerals or synthetic. Their chemical formulae are often expressed as xAl2O3·ySiO2·zH2O. It is known as E number E559.

Großalmerode is a town in the Werra-Meißner-Kreis in Hesse, Germany.

Mullite or porcelainite is a rare silicate mineral formed during contact metamorphism of clay minerals. It can form two stoichiometric forms: 3Al2O32SiO2 or 2Al2O3 SiO2. Unusually, mullite has no charge-balancing cations present. As a result, there are three different aluminium sites: two distorted tetrahedral and one octahedral.

The room-temperature form of quartz, α-quartz, undergoes a reversible change in crystal structure at 573 °C to form β-quartz. This phenomenon is called an inversion, and for the α to β quartz inversion is accompanied by a linear expansion of 0.45%. This inversion can lead to cracking of ceramic ware if cooling occurs too quickly through the inversion temperature. This is called dunting, and the resultant faults as dunts. To avoid such thermal shock faults, cooling rates not exceeding 50 °C/hour have been recommended.

Forest glass is late medieval glass produced in northwestern and central Europe from approximately 1000–1700 AD using wood ash and sand as the main raw materials and made in factories known as glasshouses in forest areas. It is characterized by a variety of greenish-yellow colors, the earlier products often being of crude design and poor quality, and was used mainly for everyday vessels and increasingly for ecclesiastical stained glass windows. Its composition and manufacture contrast sharply with Roman and pre-Roman glassmaking centered on the Mediterranean and contemporaneous Byzantine and Islamic glass making to the east.

In materials science ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) are a subgroup of composite materials and a subgroup of ceramics. They consist of ceramic fibers embedded in a ceramic matrix. The fibers and the matrix both can consist of any ceramic material, including carbon and carbon fibers.

Hessian cuisine is based on centuries-old recipes, and forms a major part of the Hesse identity. Reflecting Hesse's central location within Germany, Hessian cuisine fuses north German and south German cuisine, with heavy influence from Bavarian cuisine and Rhenish Hesse. Sour tastes dominate the cuisine, with wines and ciders, sauerkraut and handkäse with onions and vinegar popular.

Candy making or candymaking is the preparation and cookery of candies and sugar confections. Candy making includes the preparation of many various candies, such as hard candies, jelly beans, gumdrops, taffy, liquorice, cotton candy, chocolates and chocolate truffles, dragées, fudge, caramel candy, and toffee.

Triple-cooked chips are a type of chips developed by the English chef Heston Blumenthal. Blumenthal began work on the recipe in 1993, and eventually developed the three-stage cooking process. The chips are first simmered, then cooled and drained using a sous-vide technique or by freezing; deep fried at 130 °C (266 °F) and cooled again; and finally deep-fried again at 180 °C (356 °F). The result is what Blumenthal calls "chips with a glass-like crust and a soft, fluffy centre".