Related Research Articles

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science principles and methods to support legal decision-making in matters of criminal and civil law.

Chain of custody (CoC), in legal contexts, is the chronological documentation or paper trail that records the sequence of custody, control, transfer, analysis, and disposition of materials, including physical or electronic evidence. Of particular importance in criminal cases, the concept is also applied in civil litigation and more broadly in drug testing of athletes and in supply chain management, e.g. to improve the traceability of food products, or to provide assurances that wood products originate from sustainably managed forests. It is often a tedious process that has been required for evidence to be shown legally in court. Now, however, with new portable technology that allows accurate laboratory quality results from the scene of the crime, the chain of custody is often much shorter which means evidence can be processed for court much faster.

A mug shot or mugshot is a photographic portrait of a person from the shoulders up, typically taken after a person is placed under arrest. The primary purpose of the mug shot is to allow law enforcement to have a photographic record of an arrested individual to allow for identification by victims, the public and investigators. However, in the United States, entrepreneurs have recently begun to monetize these public records via the mug shot publishing industry.

A scenes of crime officer (SOCO) is an officer who gathers forensic evidence for the [[Law enforcemen They are also referred to by some forces as forensic scene investigators (FSIs), crime scene investigators (CSIs), or crime scene examiners (CSEs). SOCOs are usually not police officers, but are employed by the police forces. Evidence collected is passed to the detectives of the Criminal Investigation Department and to the forensic laboratories. The SOCOs do not investigate crimes or analyse evidence themselves. To be a SOCO, at least 5 GCSEs at Grade level 9 - 4 are required.

Alphonse Bertillon was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement creating an identification system based on physical measurements.

A crime scene is any location that may be associated with a committed crime. Crime scenes contain physical evidence that is pertinent to a criminal investigation. This evidence is collected by crime scene investigators (CSI) and law enforcement. The location of a crime scene can be the place where the crime took place or can be any area that contains evidence from the crime itself. Scenes are not only limited to a location, but can be any person, place, or object associated with the criminal behaviours that occurred.

Candid photography is photography captured without creating a posed appearance. This style is also called street photography, spontaneous photography or snap shooting. Professional photographers sometimes shoot candid photos of strangers on the street or in other public places such as parks and beaches. Candid photography captures natural expressions and moments that might not be possible to reproduce in a studio or posed photo shoot. This style of photography is most often used to capture people in their natural state without them noticing the camera. The main focus is on capturing the candid expressions and moments of life. Candid photography can be used in a variety of settings such as family gatherings, special events, and everyday street scenes. It is also a popular choice for wedding photos and professional portraits. Candid photography is often seen as a more honest representation of the subject than posed photography. To capture candid photos, the photographer may need to observe the subject from a distance or use a long lens or telephoto zoom lens. This allows for capturing the subject in their natural environment without them being aware of the camera. The photographer may need to be quick and have an eye for interesting compositions and backgrounds.

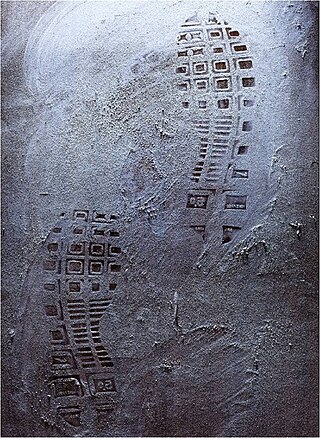

Forensic identification is the application of forensic science, or "forensics", and technology to identify specific objects from the trace evidence they leave, often at a crime scene or the scene of an accident. Forensic means "for the courts".

War photography involves photographing armed conflict and its effects on people and places. Photographers who participate in this genre may find themselves placed in harm's way, and are sometimes killed trying to get their pictures out of the war arena.

The Public Eye is a 1992 American crime thriller film produced by Sue Baden-Powell and written and directed by Howard Franklin, starring Joe Pesci and Barbara Hershey. Stanley Tucci and Richard Schiff appear in supporting roles.

A crime laboratory, often shortened to crime lab, is a scientific laboratory, using primarily forensic science for the purpose of examining evidence from criminal cases.

Forensic photography may refer to the visual documentation of different aspects that can be found at a crime scene. It may include the documentation of the crime scene, or physical evidence that is either found at a crime scene or already processed in a laboratory. Forensic photography differs from other variations of photography because crime scene photographers usually have a very specific purpose for capturing each image. As a result, the quality of forensic documentation may determine the result of an investigation; in the absence of good documentation, investigators may find it impossible to conclude what did or did not happen.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to forensic science:

Forensic art is any art used in law enforcement or legal proceedings. Forensic art is used to assist law enforcement with the visual aspects of a case, often using witness descriptions and video footage.

Arthur (Usher) Fellig, known by his pseudonym Weegee, was a photographer and photojournalist, known for his stark black and white street photography in New York City.

A unit still photographer creates still photos specifically for use in publicity and marketing of feature films and television productions. In addition to creating photographs for the promotion of a film, the still photographer contributes daily to the filming process by creating set stills. With these, the photographer is careful to record all details of the cast wardrobe, set appearance and background.

The National Bureau of Criminal Identification (NBCI), also called the National Bureau of Identification, was an agency founded by the National Chiefs of Police Union in 1896, and opened in 1897, to record identifying information on criminals and share that information with law enforcement. It was located in Chicago until 1902, at which point it was moved to Washington, D.C. William Pinkerton, co-director of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, donated his agency's collection of photographs to the newfound agency. NBCI initially only collected photographs and Bertillon records, which limited the Bureau's effectiveness. Its effectiveness greatly increased when it began collecting fingerprints. NBCI ceased to exist as an independent organization when it was absorbed into the Federal Bureau of Investigation on July 26, 1908.

Contaminated evidence is any foreign material that is introduced to a crime scene after the crime is committed. Contaminated evidence can be brought in by witnesses, suspects, victims, emergency responders, fire fighters, police officers and investigators.

Forensic firearm examination is the forensic process of examining the characteristics of firearms or bullets left behind at a crime scene. Specialists in this field try to link bullets to weapons and weapons to individuals. They can raise and record obliterated serial numbers in an attempt to find the registered owner of a weapon and look for fingerprints on a weapon and cartridges.

"f/8 and be there" is an expression popularly used by photographers to indicate the importance of taking the opportunity for a picture rather than being too concerned about using the best technique. Often attributed to the noir-style New York City photographer Weegee, it has come to represent a philosophy in which, on occasion, action is more important than reflection.

References

- ↑ Jaeger, Jens. "Police and Forensic Photography." The Oxford Companion to the Photograph. Ed. Robin Lenman: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- ↑ Platt, Richard. Forensics. Ed. Jennifer Schofield. Boston: Kingfisher Publications, 2005.

- ↑ Economist. "Most-Wanted Photography." Vol. 346, Issue 8054. 1998.

- ↑ Pozzebon, B., Freitas, A., & Trindade, M.. Fotografia Forense – Aspectos históricos – Urgência de um novo foco no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Criminalística, 6(1), 14-51. April, 2017.

- ↑ Economist. "Most-Wanted Photography." Vol. 346, Issue 8054. 1998.

- ↑ Fulford, Robert. "The Naked City: How New York's Most Famous Crime Photographer Exposed Its Darkest Edges." National Post. August 15, 2006.

- ↑ Rohde, Russell R. "Crime Photography." PSA Journal. March, 2000.