Related Research Articles

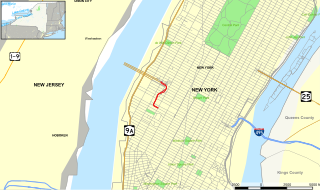

The Lincoln Tunnel is an approximately 1.5-mile-long (2.4 km) tunnel under the Hudson River, connecting Weehawken, New Jersey, to the west with Midtown Manhattan in New York City to the east. It carries New Jersey Route 495 on the New Jersey side and unsigned New York State Route 495 on the New York side. It was designed by Ole Singstad and named after Abraham Lincoln. The tunnel consists of three vehicular tubes of varying lengths, with two traffic lanes in each tube. The center tube contains reversible lanes, while the northern and southern tubes exclusively carry westbound and eastbound traffic, respectively.

A tunnel is an underground or undersea passageway. It is dug through surrounding soil, earth or rock, or laid under water, and is usually completely enclosed except for the two portals common at each end, though there may be access and ventilation openings at various points along the length. A pipeline differs significantly from a tunnel, though some recent tunnels have used immersed tube construction techniques rather than traditional tunnel boring methods.

The Holland Tunnel is a vehicular tunnel under the Hudson River that connects Hudson Square and Lower Manhattan in New York City in the east to Jersey City, New Jersey in the west. The tunnel is operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and carries Interstate 78. The New Jersey side of the tunnel is the eastern terminus of New Jersey Route 139. The Holland Tunnel is one of three vehicular crossings between Manhattan and New Jersey; the two others are the Lincoln Tunnel and George Washington Bridge.

The George Washington Bridge is a double-decked suspension bridge spanning the Hudson River, connecting Fort Lee in Bergen County, New Jersey, with the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It is named after George Washington, a Founding Father of the United States and the country's first president. The George Washington Bridge is the world's busiest motor vehicle bridge, carrying a traffic volume of over 104 million vehicles in 2019, and is the world's only suspension bridge with 14 vehicular lanes.

Route 139 is a state highway in Jersey City, New Jersey in the United States that heads east from the Pulaski Skyway over Tonnele Circle to the state line with New Jersey and New York in the Holland Tunnel, which is under the Hudson River, to New York City. The western portion of the route is a two-level highway that is charted by the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) as two separate roadways: The 1.45-mile (2.33 km) lower roadway (Route 139) between U.S. Route 1/9 (US 1/9) over Tonnele Circle and Interstate 78 (I-78) at Jersey Avenue, and the 0.83-mile (1.34 km) upper roadway running from County Route 501 and ending where it joins the lower highway as part of the 12th Street Viaduct, which ends at Jersey Avenue. The lower roadway is listed on the federal and NJ state registers of historic places since 2005. The eastern 1.32 miles (2.12 km) of the route includes the Holland Tunnel approach that runs concurrent with Interstate 78 on the one-way pair of 12th Street eastbound and 14th Street westbound. Including the concurrency, the total length of Route 139 is 2.77 miles (4.46 km).

The New York City Fire Department, officially the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) is the full-service fire department of New York City, serving all five boroughs. The FDNY is responsible for providing Fire Suppression Services, Specialized Hazardous Materials Response Services, Emergency Medical Response Services and Specialized Technical Rescue Services in the entire city.

The Bayonne Bridge is an arch bridge that spans the Kill Van Kull between Staten Island, New York, and Bayonne, New Jersey, United States. It carries New York State Route 440 and New Jersey Route 440, with the two roads connecting at the state border at the river’s center. It has the sixth-longest steel arch mainspan in the world, the longest in the world at the time of its completion. The bridge is also one of four connecting New Jersey with Staten Island; the other two roadway bridges are the Goethals Bridge in Elizabeth and Outerbridge Crossing in Perth Amboy, and the rail-only span is the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge, all of which cross the Arthur Kill.

The Hugh L. Carey Tunnel, commonly referred to as the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel, Battery Tunnel or Battery Park Tunnel, is a tolled tunnel in New York City that connects Red Hook in Brooklyn with the Battery in Manhattan. The tunnel consists of twin tubes that each carry two traffic lanes under the mouth of the East River. Although it passes just offshore of Governors Island, the tunnel does not provide vehicular access to the island. With a length of 9,117 feet (2,779 m), it is the longest continuous underwater vehicular tunnel in North America.

The Detroit–Windsor tunnel, also known as the Detroit–Canada tunnel, is an international highway tunnel connecting the cities of Detroit, Michigan, United States and Windsor, Ontario, Canada. It is the second-busiest crossing between the United States and Canada, the first being the Ambassador Bridge, which also connects the two cities, which are situated on the Detroit River.

The Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel (HRBT) is a 3.5-mile-long (5.6 km) Hampton Roads crossing for Interstate 64 (I-64) and US Route 60 (US 60). It is a four-lane facility comprising bridges, trestles, artificial islands, and tunnels under the main shipping channels for Hampton Roads harbor in the southeastern portion of Virginia in the United States.

Ole Knutsen Singstad was a Norwegian-American civil engineer best known for his work on underwater vehicular tunnels in New York City. Singstad designed the ventilation system for the Holland Tunnel, which subsequently became commonly used in other automotive tunnels, and advanced the use of the immersed tube method of underwater vehicular tunnel building, a system of constructing the tunnels with prefabricated sections.

Route 25 was a major state highway in New Jersey, United States prior to the 1953 renumbering, running from the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Camden to the Holland Tunnel in Jersey City. The number was retired in the renumbering, as the whole road was followed by various U.S. Routes: US 30 coming off the bridge in Camden, US 130 from the Camden area north to near New Brunswick, US 1 to Tonnele Circle in Jersey City, and US 1 Business to the Holland Tunnel.

The Caldecott Tunnel fire killed seven people in the third (then-northernmost) bore of the Caldecott Tunnel, on State Route 24 between Oakland and Orinda in the U.S. state of California, just after midnight on 7 April 1982. It is one of the few major tunnel fires involving a cargo normally considered to be highly flammable, namely gasoline.

On 24 March 1999, a transport truck caught fire while driving through the Mont Blanc Tunnel between France and Italy. When it stopped halfway through the tunnel, it violently combusted. Other vehicles traveling through the tunnel quickly became trapped and they also caught fire as firefighters were unable to reach the transport truck. 39 people were killed. In the aftermath, major changes were made to the tunnel to improve its safety.

The Burnley Tunnel is a tollway tunnel in Melbourne, in Victoria, Australia, which carries traffic eastbound from the West Gate Freeway to the Monash Freeway. It is part of the CityLink Tollway operated by Transurban. Running under the Yarra River and the inner suburbs of Richmond and Burnley, the tunnel provides a bypass of the central business district.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Police Department, or Port Authority Police Department (PAPD), is a law enforcement agency in New York and New Jersey, the duties of which are to protect and to enforce state and city laws at all the facilities, owned or operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ), the bi-state agency running airports, seaports, and many bridges and tunnels within the Port of New York and New Jersey. Additionally, the PAPD is responsible for other PANYNJ properties including three bus terminals, the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, and the PATH train system. The PAPD is the largest transit-related police force in the United States.

The Downtown Hudson Tubes are a pair of tunnels that carry PATH trains under the Hudson River in the United States, between New York City to the east and Jersey City, New Jersey, to the west. The tunnels run between the World Trade Center station on the New York side and the Exchange Place station on the New Jersey side.

The 178th and 179th Street Tunnels are two disused vehicular tunnels in Upper Manhattan in New York City. Originally conceived and constructed under the auspices of Robert Moses, the twin tunnels have been superseded by the Trans-Manhattan Expressway in Washington Heights, which itself runs through a cut with high-rise apartments built over it in places.

The Lincoln Tunnel Expressway is an eight block-long, mostly four-lane, north–south divided highway between the portals of the Lincoln Tunnel and West 31st Street in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Dyer Avenue is an at-grade roadway paralleling part of the mostly depressed roadway and serves traffic entering and leaving the highway and the tubes of the tunnel. Like the tunnel, the roads are owned and operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. They traverse the Manhattan neighborhoods of Hell's Kitchen and Chelsea between Ninth and Tenth avenues. The highway serves as the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel from Manhattan, with the entrance from Weehawken, New Jersey being the Lincoln Tunnel Helix.

The Lincoln Tunnel Helix, known commonly as The Helix or the Route 495 Helix, is an elevated spiral bridge freeway that carries New Jersey Route 495 to and from the Lincoln Tunnel in Weehawken, New Jersey. It is an oval-shaped 270-degree loop between the Palisades cliffs and the entrance to the tunnel. The structure, built in 1937, is owned, operated and maintained by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ).

References

- 1 2 Feinberg, Alexander (May 14, 1949). "PHONE CIRCUITS CUT; Vehicles Are Melted by 4,000 Heat – Gas and Smoke Add to Terror". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Gillespie, Angus Kress (October 16, 2011). Crossing Under the Hudson: The Story of the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels. Rutgers University Press. pp. 105–113. ISBN 978-0-81355-083-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Egilsrud, P., Prevention and Control of Highway Tunnel Fires, FHWA report RD-083-32, May 1984, pp. 6–8

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parke, Richard H. (May 14, 1949). "MEN AND MACHINES TACKLE WRECKAGE; Crew of 150 Works Into Night Amid Crumbling Walls to Clear Way for Traffic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ↑ "OXYGEN KEY FACTOR IN TUNNEL BATTLE; City's Firemen Use 4 Rescue Trucks for First Time – 100 Gas Protectors Available". The New York Times. May 14, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- 1 2 Foote, R. S., Research for Optimal Ventilation at the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels, paper B3, pp. B3-33–B3-54, Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on the Aerodynamics and Ventilation of Vehicle Tunnels, Canterbury, 1973. BHRA 1974: ISBN 0-900983-28-0

- 1 2 Feinberg, Alexander (May 15, 1949). "Tunnel Repairs Speeded; Reopening Today Sought; Month or Two Needed for Holland Tube Job, to Be Done at Night – Driver Is Cleared as Three Investigations Are Started". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ↑ It's a Brand-New Construction Job Every Night in the Holland Tunnel, Engineering News Record, July 21, 1949, pp. 32–34

- ↑ Restoration of Fire-Seared Holland Tunnel, Construction Methods and Equipment. vol. 31, no. 8, August 1949, pp. 34–38

- ↑ "HEAVY FINES ASKED TO PROTECT TUNNEL; Port Authority Would Tighten Rules on Dangerous Cargoes to Prevent Explosions WANTS ACTION BY STATES Tobin Requests Violations of Laws Be Made a Felony -Blast Inquiry Goes On". The New York Times. May 17, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ↑ "TUNNEL BAN FOR TRUCKER; Port Authority Acts to Guard Against Dangerous Cargoes". The New York Times. December 5, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved April 28, 2018.