Related Research Articles

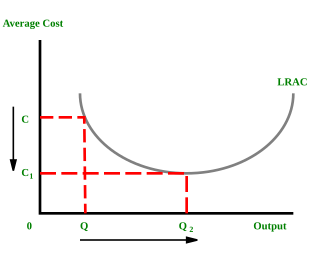

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables an increase in scale. At the basis of economies of scale, there may be technical, statistical, organizational or related factors to the degree of market control. This is just a partial description of the concept.

In an economic model, agents have a comparative advantage over others in producing a particular good if they can produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade. Comparative advantage describes the economic reality of the work gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations, which arise from differences in their factor endowments or technological progress.

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a measure of the price of specific goods in different countries and is used to compare the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currencies. PPP is effectively the ratio of the price of a basket of goods at one location divided by the price of the basket of goods at a different location. The PPP inflation and exchange rate may differ from the market exchange rate because of tariffs, and other transaction costs.

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. Proponents argue that protectionist policies shield the producers, businesses, and workers of the import-competing sector in the country from foreign competitors. Opponents argue that protectionist policies reduce trade and adversely affect consumers in general as well as the producers and workers in export sectors, both in the country implementing protectionist policies and, in the countries, protected against.

In economics, internationalization or internationalisation is the process of increasing involvement of enterprises in international markets, although there is no agreed definition of internationalization. Internationalization is a crucial strategy not only for companies that seek horizontal integration globally but also for countries that addresses the sustainability of its development in different manufacturing as well as service sectors especially in higher education which is a very important context that needs internationalization to bridge the gap between different cultures and countries. There are several internationalization theories which try to explain why there are international activities.

Paul Robin Krugman is an American economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and a columnist for The New York Times. In 2008, Krugman was the winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography. The Prize Committee cited Krugman's work explaining the patterns of international trade and the geographic distribution of economic activity, by examining the effects of economies of scale and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.

The Stolper–Samuelson theorem is a basic theorem in Heckscher–Ohlin trade theory. It describes the relationship between relative prices of output and relative factor rewards—specifically, real wages and real returns to capital.

The Heckscher–Ohlin model is a general equilibrium mathematical model of international trade, developed by Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin at the Stockholm School of Economics. It builds on David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage by predicting patterns of commerce and production based on the factor endowments of a trading region. The model essentially says that countries export the products which use their relatively abundant and cheap factors of production, and import the products which use the countries' relatively scarce factors.

International economics is concerned with the effects upon economic activity from international differences in productive resources and consumer preferences and the international institutions that affect them. It seeks to explain the patterns and consequences of transactions and interactions between the inhabitants of different countries, including trade, investment and transaction.

New trade theory (NTT) is a collection of economic models in international trade theory which focuses on the role of increasing returns to scale and network effects, which were originally developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The main motivation for the development of NTT was that, contrary to what traditional trade models would suggest, the majority of the world trade takes place between countries that are similar in terms of development, structure, and factor endowments.

The Linder hypothesis is an economics conjecture about international trade patterns: The more similar the demand structures of countries, the more they will trade with one another. Further, international trade will still occur between two countries having identical preferences and factor endowments.

Intra-industry trade refers to the exchange of similar products belonging to the same industry. The term is usually applied to international trade, where the same types of goods or services are both imported and exported.

The gravity model of international trade in international economics is a model that, in its traditional form, predicts bilateral trade flows based on the economic sizes and distance between two units. Research shows that there is "overwhelming evidence that trade tends to fall with distance."

In economics, competition is a scenario where different economic firms are in contention to obtain goods that are limited by varying the elements of the marketing mix: price, product, promotion and place. In classical economic thought, competition causes commercial firms to develop new products, services and technologies, which would give consumers greater selection and better products. The greater the selection of a good is in the market, the lower prices for the products typically are, compared to what the price would be if there was no competition (monopoly) or little competition (oligopoly).

Elhanan Helpman is an Israeli economist who is currently the Galen L. Stone Professor of International Trade at Harvard University. He is also a Professor Emeritus at the Eitan Berglas School of Economics at Tel Aviv University. Helpman is among the thirty most cited economists in the world according to IDEAS/RePEc.

In economics, gains from trade are the net benefits to economic agents from being allowed an increase in voluntary trading with each other. In technical terms, they are the increase of consumer surplus plus producer surplus from lower tariffs or otherwise liberalizing trade.

The Brander–Spencer model is an economic model in international trade originally developed by James Brander and Barbara Spencer in the early 1980s. The model illustrates a situation where, under certain assumptions, a government can subsidize domestic firms to help them in their competition against foreign producers and in doing so enhances national welfare. This conclusion stands in contrast to results from most international trade models, in which government non-interference is socially optimal.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.

Robert Christopher Feenstra is an American economist, academic and author. He is the C. Bryan Cameron Distinguished Chair in International Economics at University of California, Davis. He served as the director of the International Trade and Investment Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research from 1992 to 2016. He also served as Associate Dean in the Social Sciences at the University of California, Davis from 2014 to 2019.

James R. Markusen is an American economist, academic, and author. He is Distinguished Professor (emeritus) at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

References

- ↑ Grossman, Gene M.; Rogoff, Kenneth (1995). Handbook of International Economics. Boston: Elsevier. p. 1261. ISBN 0-444-81547-3.

- ↑ Hanson, Gordon and Chong Xiang. "The Home Market Effect and Bilateral Trade Patterns." NBER Working Paper No. 9076. July 2002. p3.

- ↑ Corden, W.M. (1970), "A Note on Economies of Scale, the Size of the Domestic Market and the Pattern of Trade", in I.A. McDougall and R.H. Snape, eds., Studies in International Economics, Amsterdam, North-Holland.

- ↑ Krugman, Paul R (1980), "Scale Economies, Product Differentiation, and the Pattern of Trade", The American Economic Review, 70(5):950-959.

- ↑ Auer, Raphael. "Taste differences, home markets, and the gains from trade." Voxeu. 19 September 2010. http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/5535.

- ↑ Helpman E. and Krugman P. R., Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Trade, Cambridge, M.A.: MIT Press, 1985.

- ↑ Head K. and Ries J., "Increasing Returns versus National Product Differentiation as An Explanation for the Pattern of U.S.-Canada Trade," American Economic Review, 2001, 91, pp.858–876.

- ↑ Feenstra R. C., Markusen J. A., and Rose A. K., "Using the Gravity Equation to Differentiate among Alternative Theories of Trade," Canadian Journal of Economics , 2001, 34, pp.430–447.

- ↑ Behrens K., Lamorgese A. R., Ottaviano G.I.P., and Tabuchi T., "Testing the Home Market Effect in A Multi-Country World: A Theory-Based Approach," Temi di discussion del Servizio Studi, No. 561, Banca D'Italia, Sep. 2005.

- ↑ Huang D. S. and Huang Y. Y., "Technology Advantage and Home-Market Effects," Working Paper, April 2007.

- ↑ Davis D., "The Home Market, Trade, and Industrial Structure," American Economic Review,1998, 88, pp.1264–1276.

- ↑ Head K., Mayertt T., and Ries J., "On the Pervasiveness of Home Market Effects," Economica, 2002, 69, pp.371–390.

- ↑ Markusen J. R. and Venables A. J., "Trade Policy with Increasing Returns and Imperfect Competition: Contradictory Results from Competing Assumptions," Journal of International Economics, 1988, 20, pp.299–316.

- ↑ Behrens K., "Market Size and Industry Location: Traded vs Non-Traded Goods," Journal of Urban Economics, 2005, 58, pp.24-44.

- ↑ Yu Z., "Trade, Market Size, and Industrial Structure: Revisiting the Home-Market Effect," Canadian Journal of Economics, 2005, 381, pp.255–272.