Hospital Sketches (1863) is a compilation of four sketches based on letters Louisa May Alcott sent home during the six weeks she spent as a volunteer nurse for the Union Army during the American Civil War in Georgetown.

Hospital Sketches (1863) is a compilation of four sketches based on letters Louisa May Alcott sent home during the six weeks she spent as a volunteer nurse for the Union Army during the American Civil War in Georgetown.

Tribulation Periwinkle opens the story by complaining, "I want something to do." She dismisses suggestions to write a book, teach, get married, or start acting. When her younger brother suggests she "go nurse the soldiers", she immediately responds, "I will!" After substantial hardship in trying to obtain a spot, she has further difficulty finding a place on the train. She then describes her travel through New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore en route to Washington DC.

Immediately after her arrival, Periwinkle must attend to the wounded from the Battle of Fredericksburg. Her first assignment is washing them before putting them to bed. She converses with the various wounded soldiers, including an Irishman and a Virginia blacksmith. The death of the blacksmith, a man named John, in particular touches her deeply.

After the Civil War broke out, the town of Concord, Massachusetts rallied, inspiring many young men to volunteer. The company assembled on the town common on April 19, 1861, the anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord as they set off. Louisa May Alcott wrote to her friend Alf Whitman that it was "a sight to behold". [1] She was disappointed that she had to stay behind, lamenting, "as I can't fight, I will content myself with working with those who can." [1] She joined local women who volunteered to sew clothes and provide other supplies. On her 30th birthday on November 29, 1862, she made up her mind to do more. She recorded in her journal, "Thirty years old. Decide to go to Washington as a nurse if I could find a place." [2] She received her orders on December 11 and made her way to Georgetown, outside of Washington, D.C. While working as a nurse, Alcott contracted typhoid fever and was treated with mercury in the form of calomel. She survived but later recorded, "I was never ill before this time, and never well afterward." [3]

While serving as a nurse, Alcott wrote several letters to her family in Concord. At the urging of others, she prepared them for publication, slightly altering and fictionalizing them. The narrator of the stories was renamed Tribulation Periwinkle but the sketches are virtually authentic to Alcott's real experiences. [4]

The first of the sketches was published on May 22, 1863, in the abolitionist magazine Boston Commonwealth edited by family friend Franklin Benjamin Sanborn. The final sketch was published on June 26. [5] Alcott herself did not care much for the writings, dismissing the idea that they were "witty", and admitted, "I wanted money." [6] The pieces received great critical and popular acclaim making Alcott an overnight success.

Transcendentalist Moncure D. Conway, who helped secure the publication of the sketches in the Commonwealth, recommended they be collected as a book. [7] The author was approached by Thomas Niles, an up-and-coming employee of Roberts Brothers, to publish the sketches in book form. Instead, she turned to the more established publisher James Redpath, who paid her $40 for the book. [8] At her father's suggestion, the book was dedicated to Hannah Stevenson, a friend who had helped Alcott secure her position as a volunteer nurse. [5] The book, priced at 50 cents, earned the author five cents in royalties for every copy sold, with an additional five cents donated to children orphaned by the war. [5] Years later, Walt Whitman contacted Redpath, hoping he would publish his own recollections as a Civil War nurse. As he wrote, the book Memoranda During the War, would be "something considerably more than mere hospital sketches." [9]

Fourteen years later after its publication, Alcott reflected on avoiding Roberts Brothers, who later published Little Women (1868): "Shortsighted Louisa! Little did you dream that this same Roberts Brothers were to help you make your fortune a few years later." [8] After that novel's success, Niles offered to republish Hospital Sketches under the Roberts Brothers imprint, and Alcott slightly expanded it. [10]

Louisa May Alcott's father Amos Bronson Alcott predicted the sketches "likely to be popular, the subject and style of treatment alike commending it to the reader, and to the Army especially. I see nothing in the way of a good appreciation of Louisa's merits as a woman and a writer. Nothing could be more surprising to her or agreeable to us." [11] Her father was right; when it proved popular, Alcott was surprised by her own success. As she wrote: "I cannot see why people like a few extracts from topsey turvey letters written on inverted tea kettles, waiting for gruel to warm, or poultices to cool, [or] for boys to wake and be tormented." [6] Henry James, Sr. wrote her a letter to applaud "her charming pictures of hospital service." [12] The Boston Evening Transcript called the book "fluent and sparkling, with touches of quiet humor and lively wit". [6] Alcott herself wrote, "I find I've done a good thing without knowing it." [12]

Amos Bronson Alcott was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and avoided traditional punishment. He hoped to perfect the human spirit and, to that end, advocated a plant-based diet. He was also an abolitionist and an advocate for women's rights.

Louisa May Alcott was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for writing the novel Little Women (1868) and its sequels Little Men (1871) and Jo's Boys (1886). Raised in New England by her transcendentalist parents, Abigail May and Amos Bronson Alcott, she grew up among many well-known intellectuals of the day, including Margaret Fuller, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Little Women is a coming-of-age novel written by American novelist Louisa May Alcott, originally published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869. The story follows the lives of the four March sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—and details their passage from childhood to womanhood. Loosely based on the lives of the author and her three sisters, it is classified as an autobiographical or semi-autobiographical novel.

Walpole is a town in Cheshire County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,633 at the 2020 census.

Abigail May Alcott Nieriker was an American artist and the youngest sister of Louisa May Alcott. She was the basis for the character Amy in her sister's semi-autobiographical novel Little Women (1868). She was named after her mother, Abigail May, and first called Abba, then Abby, and finally May, which she asked to be called in November 1863 when in her twenties.

Little Men, or Life at Plumfield with Jo's Boys, is a children's novel by American author Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), which was first published in 1871 by Roberts Brothers. The book reprises characters from her 1868–69 two-volume novel Little Women, and acts as a sequel, or as the second book in an unofficial Little Women trilogy. The trilogy ends with Alcott's 1886 novel Jo's Boys, and How They Turned Out: A Sequel to Little Men. Alcott's story recounts the life of Jo Bhaer, her husband, and the various children at Plumfield Estate School. Alcott's classic novel has been adapted to a 1934 film, a 1940 film, a 1998 film, a television series, and a Japanese animated television series.

The Wayside is a historic house in Concord, Massachusetts. The earliest part of the home may date to 1717. Later it successively became the home of the young Louisa May Alcott and her family, who named it Hillside, author Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family, and children's writer Margaret Sidney. It became the first site with literary associations acquired by the National Park Service and is now open to the public as part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

Orchard House is a historic house museum in Concord, Massachusetts, United States, opened to the public on May 27, 1912. It was the longtime home of Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888) and his family, including his daughter Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), who wrote and set her novel Little Women (1868–69) there.

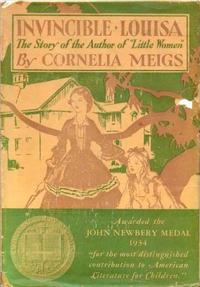

Invincible Louisa is a biography by Cornelia Meigs that won the Newbery Medal and the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award. It retells the life of Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women.

Jo's Boys, and How They Turned Out: A Sequel to "Little Men" is a novel by American author Louisa May Alcott, first published in 1886. The novel is the final book in the unofficial Little Women series. In it, Jo's children, now grown, are caught up in real world troubles.

The Concord School of Philosophy was a lyceum-like series of summer lectures and discussions of philosophy in Concord, Massachusetts, from 1879 to 1888.

William Fletcher Weld was an American shipping magnate during the Golden Age of Sail and a member of the prominent Weld family. He later invested in railroads and real estate. Weld multiplied his family's fortune into a huge legacy for his descendants and the public.

George Walker Weld (1840–1905), youngest son of William Fletcher Weld and member of the Weld Family of Boston, was a founding member of the Boston Athletic Association, which is the organizer of the present-day Boston Marathon, and the financier of the Weld Boathouse, a landmark on the Charles River.

Elizabeth Sewall Alcott was one of the two younger sisters of Louisa May Alcott. She was born in 1835 and died at the age of 22 from scarlet fever.

Anna Bronson Alcott Pratt was the elder sister of American novelist Louisa May Alcott. She was the basis for the character Margaret "Meg" of Little Women (1868), her sister's classic, semi-autobiographical novel.

John Matteson is an American professor of English and legal writing at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. He won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography for his first book, Eden's Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father.

Flower Fables also known as Queen Aster was the first work published by Louisa May Alcott and appeared on December 9, 1854. The book was a compilation of fanciful stories first written six years earlier for Ellen Emerson. The book was published in an edition of 1600 and though Alcott thought it "sold very well", she received only about $35 from the Boston publisher, George Briggs.

William Russell was an educator and elocutionist. He was formally educated in the Latin school and in the university of Glasgow; and, he came to the US in 1819, wherein that year, he took charge of Chatham Academy in Savannah, Georgia. He moved to New Haven, Connecticut, a few years later, and there he taught in the New Township Academy and also in the Hopkins Grammar School. He then devoted himself to the instruction of classes in elocution in Andover, Harvard, and Boston, Massachusetts. He edited the American Journal of Education 1826–1829. In 1830, he taught in a girls' school in Germantown, Pennsylvania, for a time with Bronson Alcott. He resumed his elocution classes in Boston and Andover in 1838, and he lectured extensively in New England and in New York State. He established a teachers' institute in New Hampshire in 1849, which he then moved to Lancaster, Massachusetts, in 1853. His subsequent life was devoted to lecturing, for the most part, before the Massachusetts teachers' institutes, under the guidance and instruction of the state board of education.

Eden's Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father is a 2007 biography by John Matteson of Louisa May Alcott, best known as the author of Little Women, and her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, an American transcendentalist philosopher and the founder of the Fruitlands utopian community. Eden's Outcasts won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Hannah Anderson Ropes was an American nurse, abolitionist, and writer.