Related Research Articles

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of the euro.

The money market is a component of the economy that provides short-term funds. The money market deals in short-term loans, generally for a period of a year or less.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis was a period of financial crisis that gripped much of East and Southeast Asia during the late 1990s. The crisis began in Thailand in July 1997 before spreading to several other countries with a ripple effect, raising fears of a worldwide economic meltdown due to financial contagion. However, the recovery in 1998–1999 was rapid, and worries of a meltdown quickly subsided.

In international economics, the balance of payments of a country is the difference between all money flowing into the country in a particular period of time and the outflow of money to the rest of the world. In other words, it is economic transactions between countries during a period of time. These financial transactions are made by individuals, firms and government bodies to compare receipts and payments arising out of trade of goods and services.

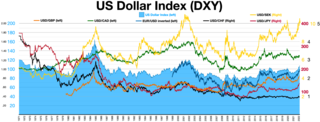

The foreign exchange market is a global decentralized or over-the-counter (OTC) market for the trading of currencies. This market determines foreign exchange rates for every currency. It includes all aspects of buying, selling and exchanging currencies at current or determined prices. In terms of trading volume, it is by far the largest market in the world, followed by the credit market.

In macroeconomics, an open market operation (OMO) is an activity by a central bank to exchange liquidity in its currency with a bank or a group of banks. The central bank can either transact government bonds and other financial assets in the open market or enter into a repo or secured lending transaction with a commercial bank. The latter option, often preferred by central banks, involves them making fixed period deposits at commercial banks with the security of eligible assets as collateral.

The Mexican peso crisis was a currency crisis sparked by the Mexican government's sudden devaluation of the peso against the U.S. dollar in December 1994, which became one of the first international financial crises ignited by capital flight.

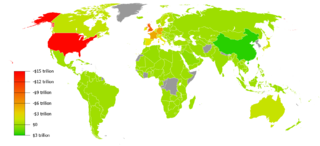

Foreign exchange reserves are cash and other reserve assets such as gold and silver held by a central bank or other monetary authority that are primarily available to balance payments of the country, influence the foreign exchange rate of its currency, and to maintain confidence in financial markets. Reserves are held in one or more reserve currencies, nowadays mostly the United States dollar and to a lesser extent the euro.

The impossible trinity is a concept in international economics and international political economy which states that it is impossible to have all three of the following at the same time:

In macroeconomics and international finance, the capital account, also known as the capital and financial account, records the net flow of investment into an economy. It is one of the two primary components of the balance of payments, the other being the current account. Whereas the current account reflects a nation's net income, the capital account reflects net change in ownership of national assets.

A currency crisis is a type of financial crisis, and is often associated with a real economic crisis. A currency crisis raises the probability of a banking crisis or a default crisis. During a currency crisis the value of foreign denominated debt will rise drastically relative to the declining value of the home currency. Generally doubt exists as to whether a country's central bank has sufficient foreign exchange reserves to maintain the country's fixed exchange rate, if it has any.

Capital began to flow in and out of Japan following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, but policy restricted loans from overseas. In the aftermath of World War II, Japan was a debtor nation until the mid-1960s. Subsequently, capital controls were progressively removed, in part as a result of agreements with the United States. This process led to rapid expansion of capital flows during the 1970s and especially the 1980s, when Japan became a creditor nation and the largest net investor in the world. This credit position resulted both from foreign direct investment by Japanese corporations, and portfolio investment. In particular, the rapid increase of Japan's direct investments overseas, much exceeding foreign investment in Japan, led to some tension with the US at the end of the 1980s.

Foreign exchange risk is a financial risk that exists when a financial transaction is denominated in a currency other than the domestic currency of the company. The exchange risk arises when there is a risk of an unfavourable change in exchange rate between the domestic currency and the denominated currency before the date when the transaction is completed.

Currency depreciation is the loss of value of a country's currency with respect to one or more foreign reference currencies, typically in a floating exchange rate system in which no official currency value is maintained. Currency appreciation in the same context is an increase in the value of the currency. Short-term changes in the value of a currency are reflected in changes in the exchange rate.

Capital account convertibility is a feature of a nation's financial regime that centers on the ability to conduct transactions of local financial assets into foreign financial assets freely or at market determined exchange rates. It is sometimes referred to as capital asset liberation or CAC.

A sudden stop in capital flows is defined as a sudden slowdown in private capital inflows into emerging market economies, and a corresponding sharp reversal from large current account deficits into smaller deficits or small surpluses. Sudden stops are usually followed by a sharp decrease in output, private spending and credit to the private sector, and real exchange rate depreciation. The term “sudden stop” was inspired by a banker’s comment on a paper by Rüdiger Dornbusch and Alejandro Werner about Mexico, that “it is not speed that kills, it is the sudden stop”.

Currency intervention, also known as foreign exchange market intervention or currency manipulation, is a monetary policy operation. It occurs when a government or central bank buys or sells foreign currency in exchange for its own domestic currency, generally with the intention of influencing the exchange rate and trade policy.

In macroeconomics, sterilization is action taken by a country's central bank to counter the effects on the money supply caused by a balance of payments surplus or deficit. This can involve open market operations undertaken by the central bank whose aim is to neutralize the impact of associated foreign exchange operations. The opposite is unsterilized intervention, where monetary authorities have not insulated their country's domestic money supply and internal balance against foreign exchange intervention.

Fear of floating refers to situations where a country prefers a fixed exchange rate to a floating exchange rate regime. This is more relevant in emerging economies, especially when they suffered from financial crisis in the last two decades. In foreign exchange markets of the emerging market economies, there is evidence showing that countries who claim they are floating their currency, are actually reluctant to let the nominal exchange rate fluctuate in response to macroeconomic shocks. In the literature, this is first convincingly documented by Calvo and Reinhart with "fear of floating" as the title of one of their papers in 2000. Since then, this widespread phenomenon of reluctance to adjust exchange rates in emerging markets is usually called "fear of floating". Most of the studies on "fear of floating" are closely related to literature on costs and benefits of different exchange rate regimes.

Prudential capital controls are typical ways of prudential regulation that takes the form of capital controls and regulates a country's capital account inflows. Prudential capital controls aim to mitigate systemic risk, reduce business cycle volatility, increase macroeconomic stability, and enhance social welfare.

References

- 1 2 Martin, Micheal F.; Morrison, Wayne M. (July 21, 2008). China's "Hot Money" Problems. Congressional Research Service (Report). RS22921.

- ↑ Hot Money and Serial Financial Crises, Anton Korinek, IMF Economic Review (2011)

- 1 2 Calvo, Guillermo A.; Leiderman, Leonardo; Reinhart, Carmen M. (1996). "Inflows of Capital to Developing Countries in the 1990s". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 10 (2): 123–139. doi:10.1257/jep.10.2.123.

- ↑ Baily, Martin N.; Farrell, Diana; Lund, Susan (May 2000). "Hot Money". McKinsey Quarterly.

- ↑ Baily, Martin N.; Farrell, Diana; Lund, Susan (2000). "The Color of Hot Money". Foreign Affairs. 79 (2): 99–109. doi:10.2307/20049643. JSTOR 20049643.

- 1 2 Reinhart, Carmen; Reinhart, Vincent (2008). "Capital Flow Bonanzas: An Encompassing View of the Past and Present". National Bureau of Economic Research . Working Paper Series. doi:10.3386/w14321.

- ↑ Caballero, Ricardo J.; Lorenzoni, Guido (April 19, 2007). "Persistent Appreciation and Overshooting: A Normative Analysis" (PDF). MIT and NBER.

- ↑ Short Term Capital Flows, by Dani Rodrik, Andres Velasco, 1999 NBER

- 1 2 "Capital Inflows: The Role of Controls" (PDF). IMF Staff Position Note. February 19, 2010.

- ↑ Turkey surprises with interest rate cut, by Delphine Strauss, Financial Times, December 16, 2010

- ↑ Bryant, Steve (Feb 14, 2011). "Simsek Says $8 Billion 'Hot Money' Left Turkey". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ China enhances efforts to curb hot money inflow, China Daily, November 09, 2011

- ↑ Rana, Pradumna B. (1998). Controls on Short-Term Capital Inflows - The Latin American Experience and Lessons For DMCs (PDF). Economics and Development Resource Center Briefing Notes (Report). Asian Development Bank.

- ↑ Cardarelli, Roberto; Kose, M. Ayhan; Elekdag, Selim (2009). "Capital Inflows: Macroeconomic Implications and Policy Responses". Imf Working Papers. 09 (40): 1. doi:10.5089/9781451871883.001.

- ↑ Capital Flows in the APEC Region. Occasional Papers. 1995. doi:10.5089/9781557754660.084. ISBN 978-1-55775-466-0.