Peter Carl Fabergé, also known as Karl Gustavovich Fabergé, was a Russian jeweller best known for the famous Fabergé eggs made in the style of genuine Easter eggs, but using precious metals and gemstones rather than more mundane materials. He was one of the sons of the founder of the famous jewelry legacy House of Fabergé.

A tiara is a jeweled head ornament. Its origins date back to ancient Iran, which was then adapted by Greco-Romans. In the late 18th century, the tiara came into fashion in Europe as a prestigious piece of jewelry to be worn by women at formal occasions. The basic shape of the modern tiara is a (semi-)circle, usually made of silver, gold or platinum, and richly decorated with precious stones, pearls or cameos.

A Fabergé egg is a jewelled egg created by the jewellery firm House of Fabergé, in Saint Petersburg, Russia. As many as 69 were created, of which 57 survive today. Virtually all were manufactured under the supervision of Peter Carl Fabergé between 1885 and 1917. The most famous are his 52 "Imperial" eggs, 46 of which survive, made for the Russian emperors Alexander III and Nicholas II as Easter gifts for their wives and mothers. Fabergé eggs are worth millions of dollars and have become symbols of opulence.

The Imperial crown of Russia, also known as the great imperial crown, was used for the coronation of the monarchs of Russia from 1762 until the Russian monarchy's abolition in 1917. The great imperial crown was first used in the coronation by Catherine the Great, and it was last worn at the coronation of Nicholas II. It was displayed prominently next to Nicholas II on a cushion at the State Opening of the Russian Duma inside the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in 1906. It survived the 1917 revolution and ensuing civil war and is currently on display in Moscow at the Kremlin Armoury's State Diamond Fund.

Gustav Fabergé was a Russian jeweller of Baltic German origin and the father of Peter Carl Fabergé, maker of Fabergé eggs. He established his own business in Saint Petersburg, which his son inherited.

The Imperial Coronation egg is a jewelled Fabergé egg made under the supervision of the Russian jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé in 1897 by Fabergé ateliers, Mikhail Perkhin and Henrik Wigstrom. The egg was made to commemorate Tsarina, Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna.

A Fabergé workmaster was a skilled craftsman who owned his own workshop and produced jewelry, silver or objets d'art for the House of Fabergé.

The House of Fabergé was a jewellery firm founded in 1842 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, by Gustav Faberge, using the accented name Fabergé. Gustav's sons – Peter Carl and Agathon – and grandsons followed him in running the business until it was nationalised by the Bolsheviks in 1918. The firm was famous for designing elaborate jewel-encrusted Fabergé eggs for the Russian Tsars, and for a range of other work of high quality and intricate detail. In 1924, Peter Carl's sons Alexander and Eugène Fabergé opened a firm called Fabergé & Cie in Paris, France, making similar jewellery items and adding the name of the city to their firm's stamp, styling it FABERGÉ, PARIS.

The Lilies of the Valley egg is a jewelled Fabergé egg made under the supervision of the Russian jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé in 1898 by Fabergé ateliers. The supervising goldsmith was Michael Perchin. The egg is one of the three eggs in the Art Nouveau style. It was presented on April 5 to Tsar Nicholas II, who gave it as a gift to his wife, the Tsarina, Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna. The egg is part of the Victor Vekselberg Collection, owned by The Link of Times Foundation and housed in the Fabergé Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Garrard & Co. Limited, formerly Asprey & Garrard Limited, designs and manufactures luxury jewellery and silver. George Wickes founded Garrard in London in 1735 and the brand is headquartered at Albemarle Street in Mayfair, London. Garrard also has a presence in a number of other locations globally. Garrard was the first official and most notably important Crown Jeweller of the United Kingdom having supplied jewels for Queen Victoria herself, and was charged with the upkeep of the British Crown Jewels, from 1843 to 2007, and was responsible for the creation of many tiaras and jewels still worn by the British royal family today. As well as jewellery, Garrard is known for having created some of the world's most illustrious sporting trophies, including the Americas Cup, the ICC Cricket World Cup Trophy and a number of trophies for Royal Ascot in its role as Official Trophies and Silverware Supplier, which originally dates back to the first Gold Cup in 1842.

Wartski is a British family firm of antique dealers specialising in Russian works of art; particularly those by Carl Fabergé, fine jewellery and silver. Founded in North Wales in 1865, the business is located at 60 St James's Street, London, SW1. The company holds royal appointments as jewellers to Charles III and before her death, Elizabeth II.

Henrik Immanuel Wigström a Finnish silver & goldsmith, was one of the most important Fabergé workmasters along with Michael Perchin. Perchin was the head workmaster from 1886 until his death in 1903, when he was succeeded by his chief assistant Henrik Wigström. These two workmasters were responsible for almost all the imperial Easter eggs.

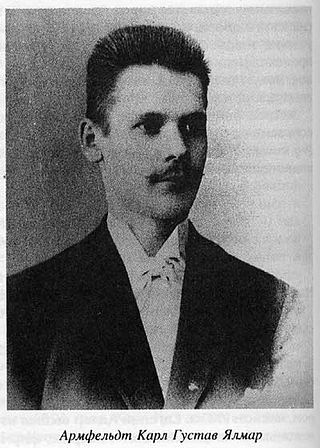

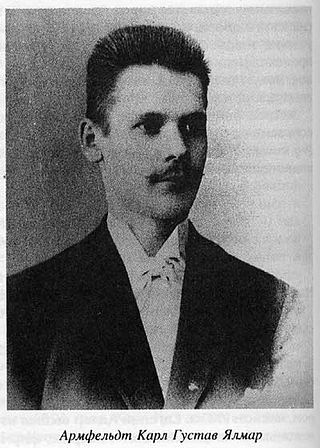

Karl Gustaf (Gustav) Hjalmar Armfeldt was a Finnish silversmith and Fabergé workmaster. He was born in Artjärvi, Finland.

August Wilhelm Holmström was a Finnish silver- and goldsmith. Born in Helsinki, Finland, he became an apprentice at the workshop of jeweller Karl Herold in St. Petersburg 1845—1850, master in 1857 with his own workshop.

Anders (Antti) Juhaninpoika Nevalainen was a Finnish gold- and silversmith, and a Fabergé workmaster.

Stefan Wäkevä, a Finnish silversmith, and a Fabergé workmaster. Born 4 November in Väkevälä village Säkkijärvi in the Viipuri Province of the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1833. Apprentice in St. Petersburg at the workshop of silversmith Olof Fredrik Wennerström in 1843. Journeyman at the age of fourteen in 1847. Master in 1856. Wäkevä's workshop at 41 of the fifth of Roždestvenskaya (Sovetskaya) Street supplied Fabergé with silverware, mostly tea-services, tankards and punch bowls.

Feodor Ivanovich Rückert,, was a silversmith, goldsmith, and Fabergé workmaster of German origin.

James Steuart Shanks, (1826–1911), second son of the coachmaker Robert Shanks was a British merchant living in Moscow. James studied at Leiden University and he came of age in 1845 at which point he inherited from his uncle Robert How. In 1852 James established the Moscow shop 'Shanks & Bolin, Magasin Anglais' with Henrik Conrad Bolin, younger brother of Carl Edvard Bolin, the St. Petersburg jeweller of House of Bolin. Two of James' children made significant contributions to art and literature.

Jérémie Pauzié was a Genevan diamond jeweler, artist and memoirist, known for his work for the Russian Imperial court and the Imperial Crown of Russia, which he created with the court's jeweler Georg Friedrich Ekart.

Fauxbergé is a term coined to generally describe items that are faking a higher quality or status and in specific terms relates to the House of Fabergé, which was a Russian jewellery firm founded in 1842 in Saint Petersburg and nationalised by the Bolsheviks in 1918. The term was first mentioned in a publication by auctioneer and Fabergé book author Archduke Géza of Austria in his article "Fauxbergé" published in Art and Auction in 1994. He also used it during the exhibition "Fabergé in America" in 1996 and subsequently.