Related Research Articles

Human rights are moral principles, or norms, for certain standards of human behaviour and are regularly protected as substantive rights in substantive law, municipal and international law. They are commonly understood as inalienable, fundamental rights "to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being" and which are "inherent in all human beings", regardless of their age, ethnic origin, location, language, religion, ethnicity, or any other status. They are applicable everywhere and at every time in the sense of being universal, and they are egalitarian in the sense of being the same for everyone. They are regarded as requiring empathy and the rule of law, and imposing an obligation on persons to respect the human rights of others; it is generally considered that they should not be taken away except as a result of due process based on specific circumstances.

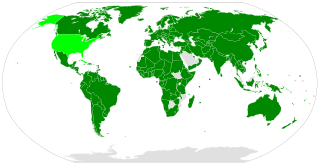

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights and rights to due process and a fair trial. It was adopted by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI) on 16 December 1966 and entered into force on 23 March 1976 after its thirty-fifth ratification or accession. As of June 2022, the Covenant has 173 parties and six more signatories without ratification, most notably the People's Republic of China and Cuba; North Korea is the only state that has tried to withdraw.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 1976. It commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to all individuals including those living in Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories. The rights include labour rights, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. As of February 2024, the Covenant has 172 parties. A further four countries, including the United States, have signed but not ratified the Covenant.

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

Human rights protection is enshrined in the Basic Law and its Bill of Rights Ordinance (Cap.383). By virtue of the Bill of Rights Ordinance and Basic Law Article 39, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is put into effect in Hong Kong. Any local legislation that is inconsistent with the Basic Law can be set aside by the courts. This does not apply to national legislation that applies to Hong Kong, such as the National Security Law, even if it is inconsistent with the Bills of Rights Ordinance, ICCPR, or the Basic Law.

The right to property, or the right to own property, is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely and is typically heavily constrained insofar as property is owned by legal persons and where it is used for production rather than consumption. The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is credited as a significant precedent for the legal protection of individual property rights.

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, otherwise known as the European Convention on Bioethics or the European Bioethics Convention, is an international instrument aiming to prohibit the misuse of innovations in biomedicine and to protect human dignity. The Convention was opened for signature on 4 April 1997 in Oviedo, Spain and is thus otherwise known as the Oviedo Convention. The International treaty is a manifestation of the effort on the part of the Council of Europe to keep pace with developments in the field of biomedicine; it is notably the first multilateral binding instrument entirely devoted to biolaw. The Convention entered into force on 1 December 1999.

Human rights in New Zealand are addressed in the various documents which make up the constitution of the country. Specifically, the two main laws which protect human rights are the New Zealand Human Rights Act 1993 and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. In addition, New Zealand has also ratified numerous international United Nations treaties. The 2009 Human Rights Report by the United States Department of State noted that the government generally respected the rights of individuals, but voiced concerns regarding the social status of the indigenous population.

The Cook Islands are 15 small islands scattered over 2 million km squared of the South Pacific. According to the latest census, the nation has a total population of approximately 18,000 people. Spread in population between the mainland capital, Rarotonga, and the Outer Islands mean inequality in terms of delivery of public services. Internal migration between Rarotonga and the Outer Islands is relatively high due to lack of schooling and employment opportunities, and increased living standards and availability of medical and educational services in Rarotonga.

The right to sexuality incorporates the right to express one's sexuality and to be free from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. Although it is equally applicable to heterosexuality, it also encompasses human rights of people of diverse sexual orientations, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, and the protection of those rights. The right to sexuality and freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation is based on the universality of human rights and the inalienable nature of rights belonging to every person by virtue of being human.

The right to adequate clothing, or the right to clothing, is recognized as a human right in various international human rights instruments; this, together with the right to food and the right to housing, are parts of the right to an adequate standard of living as recognized under Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The right to clothing is similarly recognized under Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

Local government bodies in New Zealand have responsibilities under the Local Government Act 2002 (LGA) to perform a wide range of functions, and provide a wide range of services to the communities they represent. There is not an explicit focus on human rights in New Zealand local government, or any direct reference to human rights under the LGA. Local bodies in New Zealand are required to act in a way that is consistent with the rights guaranteed under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (NZBORA). Internationally there is growing consideration of how local government does and could promote and protect fundamental rights.

Structural discrimination occurs in a society "when an entire network of rules and practices disadvantages less empowered groups while serving at the same time to advantage the dominant group".

Labour rights in New Zealand are largely covered by both statute, particularly the Employment Relations Act 2000, and common law. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment carries out most of the day to day administrative functions surrounding labour rights and their practical application in the state.

As prescribed in the Constitution of Tokelau, individual human rights are those found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and reflected in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. When exercising these rights, there must be proper recognition of the rights of others and to the community as a whole. If an individual believes their rights have been breached they may go to the Council for the Ongoing Government who may make any appropriate order to protect that individual’s rights. There have been no such complaints to date.

The right to family life is the right of all individuals to have their established family life respected, and to have and maintain family relationships. This right is recognised in a variety of international human rights instruments, including Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 23 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Disability rights are not specifically addressed by legislation in New Zealand. Instead, disability rights are addressed through human rights legislation. Human rights in New Zealand are protected by the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 and the Human Rights Act 1993. New Zealand also signed and ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2008.

The proposed Convention on the Rights of Older Persons (UNCROP) is likely to be the next major human rights treaty adopted by the United Nations. The proposed treaty will seek to remedy the fragmented human rights structure for Older Persons, and will focus on reaffirming critical human rights which are of concern to older persons. The focus of the treaty will be persons over 60 years of age, which is a growing demographic worldwide due to increased population ageing. The treaty follows from the success of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child which has seen near universal acceptance since 1989. Where the UNCRC focuses on the rights of younger persons, the UNCROP will address those who form the older portion of society, who according to United Nations reports, are becoming increasingly vulnerable as a group without applicable normative standards of human rights law. Support for a Convention is becoming increasingly popular, as human rights groups including the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), HelpAge International, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, the International Labour Organization, and many other NGOs and states have expressed support for a universal instrument. A raising number of NGOs from across the world have joined forces in advocating for a Convention in the Global Alliance for the Rights of Older Persons (GAROP) which has been set up out of the need to strengthen the rights of older persons worldwide. With population ageing, the human rights of the growing number of older persons have become an increasingly important issue. Among the human rights issues faced by older persons are ageist attitudes leading to discrimination, exclusion and constraints on the legal capacity, autonomy and independent living of older people. Existing human rights violations have been further exacerbated and put on the spotlight by the COVID-19 pandemic. Older people have been denied access to health services and became prone to physical and social isolation. The stigmatisation of older people and ageist images of older persons have also become more evident. The debate surrounding the convention focuses on the implementation and safeguarding of older persons’ human rights aiming to set normative standards of human rights for older persons in an international legally binding instrument. An underlying common factor and root cause of many of human rights violations experienced by older persons, along with its ubiquitous, prevalent, and surreptitious nature, is ageism. Ageism, as defined by the World Health Organization, refers to the stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination towards others or oneself based on age. A UNCROP would go a long way to tackle ageism. Individual relationships generally fall outside of current human rights law, which seeks to present standards of relations between states and individuals. Therefore, it has been suggested that the proposed human rights convention for older persons ought to be drafted as an anti-discrimination convention. However, this would not be consistent with other multilateral human rights conventions such as the ICCPR and ICESCR which set normative standards.

Fair trade is where a farmer or craftsperson is paid a fair price for their product, one that represents its true worth, not just the lowest price that it is possible to pay. This is a price that covers the cost of production and enables the producer to live with dignity. Fair Trade New Zealand is an organisation that was launched in 2005 which supports fair trade by ensuring that farmers and workers' rights are not exploited. According to Oxfam New Zealand, there are several companies to support fairly traded goods from, which are exported to New Zealand. From 2013-2014 there were 42 Fair Trade Licensees and Traders in New Zealand. From 2015-2016 this number rose to 54 Fair Trade Licensees and Traders in New Zealand. Gwen Green, Oxfam's Engagement Director, says: "when farmers are paid fairly for their products, we see people able to make real improvements to their lives and their communities. Producers who used to struggle to feed their families are able to give their children an education, and communities can build schools and develop businesses. It is one of the smart solutions to poverty". In 2009, Wellington became the first fair trade capital city in the Southern Hemisphere. In 2017, Whangarei was recognised by the Fair Trade Association of Australia New Zealand as being one of four fair trade councils in New Zealand, and the first fair trade district in New Zealand.

References

- ↑ Office for Senior Citizens Towards A Society for All Ages: New Zealand Positive Ageing Strategy – Goals and Key Actions (Ministry of Social Development, April 2001)

- ↑ OHCHR.org

- ↑ Universal Declaration of Human Rights GA Res 217A, III, art 1

- ↑ UDHR Article 25

- ↑ State ratification dates

- ↑ ICCPR

- ↑ ICESCR

- ↑ CRPD

- ↑ ICMW

- ↑ Marthe Fredvang and Simon Biggs ‘The rights of older persons: protection and gaps under human rights law’ at 10, Social Policy working paper no.16, The Centre for Public Policy 2012, ISBN 978-1-921623-34-9

- ↑ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Normative standards in international human rights law in relation to older persons (United Nations, Analytical Outcome Paper, 2012 at 3)

- ↑ United Nations Principles for Older Persons GA Res 46/91, A/RES/46/91 (1991)

- ↑ Marthe Fredvang and Simon Biggs ‘The rights of older persons: protection and gaps under human rights law’ at 13, Social Policy working paper no.16, The Centre for Public Policy 2012, ISBN 978-1-921623-34-9

- ↑ Sylvia Bell and Judy McGregor ‘Human rights law and older people’ in Kate Diesfeld and Ian McIntosh (eds) Elder Law in New Zealand at 184

- ↑ NZBORA 1990

- ↑ Sylvia Bell and Judy McGregor ‘Human rights law and older people’ in Kate Diesfeld and Ian McIntosh (eds) Elder Law in New Zealand at 185

- ↑ Office for Senior Citizens Towards A Society for All Ages: New Zealand Positive Ageing Strategy – Goals and Key Actions (Ministry of Social Development, April 2001)

- ↑ Judith Davey and Kathy Glasgow "Positive Ageing - A Critical Analysis" (2006) 2 (4) Policy Quarterly 21

- ↑ "Retirement age". New Zealand Government. 2 October 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ↑ New Zealand Human Rights Commission's Response to the Human Rights of Older Persons

- ↑ Office for Senior Citizens, 2014 Report on the Positive Ageing Strategy, April 2015

- ↑ New Zealand Human Rights Commission

- ↑ StudyLink

- ↑ s69AA Employment Relations Act 2000

- ↑ Office for Senior Citizens, 2014 Report on the Positive Ageing Strategy, April 2015

- ↑ New Zealand Human Rights Commission's Response to the Human Rights of Older Persons

- ↑ Work and Income

- ↑ Office for Senior Citizens, 2014 Report on the Positive Ageing Strategy, April 2015