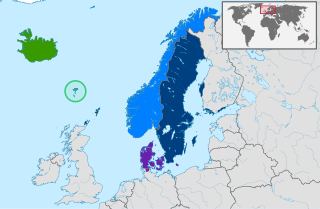

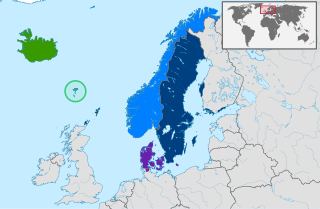

Scandinavia is a subregion of Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. Scandinavia most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also refer to the Scandinavian Peninsula. In English usage, Scandinavia is sometimes used as a synonym for Nordic countries. Iceland and the Faroe Islands are sometimes included in Scandinavia for their ethnolinguistic relations with Sweden, Norway and Denmark. While Finland differs from other Nordic countries in this respect, some authors call it Scandinavian due to its economic and cultural similarities.

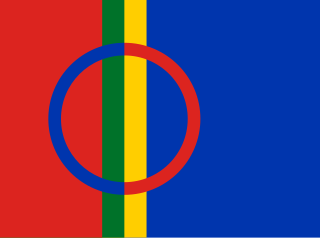

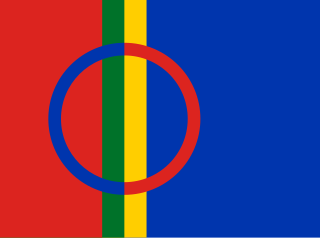

The Sámi are the traditionally Sámi-speaking indigenous people inhabiting the region of Sápmi, which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and of the Kola Peninsula in Russia. The region of Sápmi was formerly known as Lapland, and the Sámi have historically been known in English as Lapps or Laplanders, but these terms are regarded as offensive by the Sámi, who prefer their own endonym, e.g. Northern Sámi Sápmi. Their traditional languages are the Sámi languages, which are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.

Sápmi is the cultural region traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people. Sápmi includes the northern parts of Fennoscandia, also known as the "Cap of the North".

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also referred to as the Nordic languages, a direct translation of the most common term used among Danish, Faroese, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish scholars and people.

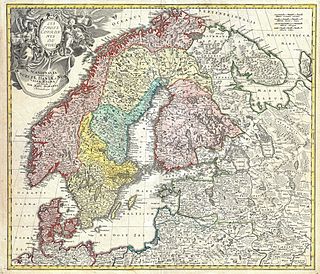

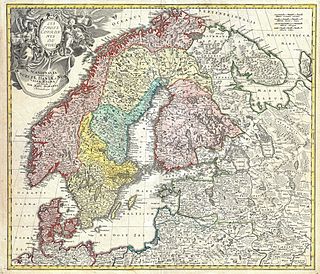

Kvenland, known as Cwenland, Qwenland, Kænland, and similar terms in medieval sources, is an ancient name for an area in Fennoscandia and Scandinavia. Kvenland, in that or nearly that spelling, is known from an Old English account written in the 9th century, which used information provided by Norwegian adventurer and traveler Ohthere, and from Nordic sources, primarily Icelandic. A possible additional source was written in the modern-day area of Norway. All known Nordic sources date from the 12th and 13th centuries. Other possible references to Kvenland by other names and spellings are also discussed here.

Kvens are a Balto-Finnic ethnic group indigenous to the northern regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and parts of Russia. In 1996, Kvens were granted minority status in Norway, and in 2005 the Kven language was recognized as a minority language in Norway.

Finns or Finnish people are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland. Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these countries as well as those who have resettled. Some of these may be classified as separate ethnic groups, rather than subgroups of Finns. These include the Kvens and Forest Finns in Norway, the Tornedalians in Sweden, and the Ingrian Finns in Russia.

The Fenni were an ancient people of northeastern Europe, first described by Cornelius Tacitus in Germania in AD 98.

The Sámi people are a Native people of northern Europe inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses northern parts of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The traditional Sámi lifestyle, dominated by hunting, fishing and trading, was preserved until the Late Middle Ages, when the modern structures of the Nordic countries were established.

Bjarmaland was a territory mentioned in Norse sagas from the Viking Age and in geographical accounts until the 16th century. The term is usually understood to have referred to the southern shores of the White Sea and to the basin of the Northern Dvina River as well as, presumably, to some of the surrounding areas. Today, those territories comprise a part of the Arkhangelsk Oblast of Russia, as well as the Kola Peninsula.

Fennoscandia, or the Fennoscandian Peninsula, is a peninsula in Europe which includes the Scandinavian and Kola peninsulas, mainland Finland, and Karelia. Administratively, this roughly encompasses the mainlands of Finland, Norway and Sweden, as well as Murmansk Oblast, much of the Republic of Karelia, and parts of northern Leningrad Oblast in Russia.

The Scandinavian Peninsula became ice-free around the end of the last ice age. The Nordic Stone Age begins at that time, with the Upper Paleolithic Ahrensburg culture, giving way to the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers by the 7th millennium BC. The Neolithic stage is marked by the Funnelbeaker culture, followed by the Pitted Ware culture.

The history of Scandinavia is the history of the geographical region of Scandinavia and its peoples. The region is located in Northern Europe, and consists of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Finland and Iceland are at times, especially in English-speaking contexts, considered part of Scandinavia.

Swedish is the official language of Sweden and is spoken by the vast majority of the 10.23 million inhabitants of the country. It is a North Germanic language and quite similar to its sister Scandinavian languages, Danish and Norwegian, with which it maintains partial mutual intelligibility and forms a dialect continuum. A number of regional Swedish dialects are spoken across the country. In total, more than 200 languages are estimated to be spoken across the country, including regional languages, indigenous Sámi languages, and immigrant languages.

Genetic studies on Sami is the genetic research that have been carried out on the Sami people. The Sami languages belong to the Uralic languages family of Eurasia.

The Baltic Finnic peoples, often simply referred to as the Finnic peoples, are the peoples inhabiting the Baltic Sea region in Northern and Eastern Europe who speak Finnic languages. They include the Finns, Estonians, Karelians, Veps, Izhorians, Votes, and Livonians. In some cases the Kvens, Ingrians, Tornedalians and speakers of Meänkieli are considered separate from the Finns.

The Sámi languages, also rendered in English as Sami and Saami, are a group of Uralic languages spoken by the Indigenous Sámi peoples in Northern Europe. There are, depending on the nature and terms of division, ten or more Sami languages. Several spellings have been used for the Sámi languages, including Sámi, Sami, Saami, Saame, Sámic, Samic and Saamic, as well as the exonyms Lappish and Lappic. The last two, along with the term Lapp, are now often considered pejorative.

The Finnic peoples, or simply Finns, are the nations who speak languages traditionally classified in the Finnic language family, and which are thought to have originated in the region of the Volga River. The largest Finnic peoples by population are the Finns, the Estonians, the Mordvins (800,000), the Mari (570,000), the Udmurts (550,000), the Komis (330,000) and the Sámi (100,000).

The origin of the Sámi has been of research interest since at least the early 17th century. Initially, the Sámi were grouped together with ethnic Finns, due to the relative similarity between the Sámi languages and Finnish. When biological anthropology was developed in the 19th century, Sámi were seen instead to differ from surrounding peoples, which in turn led to the theory that the Sámi had developed as an isolated people during the Ice Age, when they would have overwintered by the Arctic Ocean. This theory was eventually abandoned.

The name Finn is an ethnonym that in ancient times usually referred to the Sámi peoples, but now refers almost exclusively to the Finns.