Related Research Articles

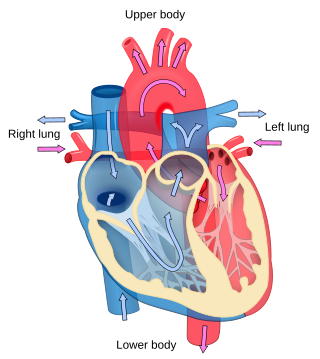

Cardiology is the study of the heart. Cardiology is a branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the heart and the cardiovascular system. The field includes medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart disease, and electrophysiology. Physicians who specialize in this field of medicine are called cardiologists, a specialty of internal medicine. Pediatric cardiologists are pediatricians who specialize in cardiology. Physicians who specialize in cardiac surgery are called cardiothoracic surgeons or cardiac surgeons, a specialty of general surgery.

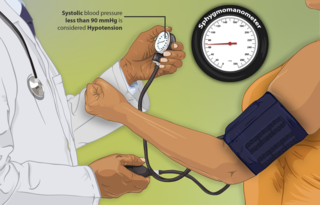

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure" refers to the pressure in a brachial artery, where it is most commonly measured. Blood pressure is usually expressed in terms of the systolic pressure over diastolic pressure in the cardiac cycle. It is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) above the surrounding atmospheric pressure, or in kilopascals (kPa).

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure (HBP), is a long-term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms. It is, however, a major risk factor for stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, peripheral arterial disease, vision loss, chronic kidney disease, and dementia. Hypertension is a major cause of premature death worldwide.

Hypertensive retinopathy is damage to the retina and retinal circulation due to high blood pressure.

Hypotension is low blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood. Blood pressure is indicated by two numbers, the systolic blood pressure and the diastolic blood pressure, which are the maximum and minimum blood pressures, respectively. A systolic blood pressure of less than 90 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) or diastolic of less than 60 mmHg is generally considered to be hypotension. Different numbers apply to children. However, in practice, blood pressure is considered too low only if noticeable symptoms are present.

Antihypertensives are a class of drugs that are used to treat hypertension. Antihypertensive therapy seeks to prevent the complications of high blood pressure, such as stroke, heart failure, kidney failure and myocardial infarction. Evidence suggests that reduction of the blood pressure by 5 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 34% and of ischaemic heart disease by 21%, and can reduce the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. There are many classes of antihypertensives, which lower blood pressure by different means. Among the most important and most widely used medications are thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBs), and beta blockers.

Nifedipine, sold under the brand names Adalat and Procardia among others, is a calcium channel blocker medication used to manage angina, high blood pressure, Raynaud's phenomenon, and premature labor. It is one of the treatments of choice for Prinzmetal angina. It may be used to treat severe high blood pressure in pregnancy. Its use in preterm labor may allow more time for steroids to improve the baby's lung function and provide time for transfer of the mother to a well qualified medical facility before delivery. It is a calcium channel blocker of the dihydropyridine type. Nifedipine is taken by mouth and comes in fast- and slow-release formulations.

Hypertensive kidney disease is a medical condition referring to damage to the kidney due to chronic high blood pressure. It manifests as hypertensive nephrosclerosis. It should be distinguished from renovascular hypertension, which is a form of secondary hypertension, and thus has opposite direction of causation.

A hypertensive emergency is very high blood pressure with potentially life-threatening symptoms and signs of acute damage to one or more organ systems. It is different from a hypertensive urgency by this additional evidence for impending irreversible hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD). Blood pressure is often above 200/120 mmHg, however there are no universally accepted cutoff values. Signs of organ damage are discussed below.

Severely elevated blood pressure is referred to as a hypertensive crisis, as blood pressure at this level confers a high risk of complications. People with blood pressures in this range may have no symptoms, but are more likely to report headaches and dizziness than the general population. Other symptoms accompanying a hypertensive crisis may include visual deterioration due to retinopathy, breathlessness due to heart failure, or a general feeling of malaise due to kidney failure. Most people with a hypertensive crisis are known to have elevated blood pressure, but additional triggers may have led to a sudden rise.

Hypertensive heart disease includes a number of complications of high blood pressure that affect the heart. While there are several definitions of hypertensive heart disease in the medical literature, the term is most widely used in the context of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding categories. The definition includes heart failure and other cardiac complications of hypertension when a causal relationship between the heart disease and hypertension is stated or implied on the death certificate. In 2013 hypertensive heart disease resulted in 1.07 million deaths as compared with 630,000 deaths in 1990.

Hypertensive encephalopathy (HE) is general brain dysfunction due to significantly high blood pressure. Symptoms may include headache, vomiting, trouble with balance, and confusion. Onset is generally sudden. Complications can include seizures, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, and bleeding in the back of the eye.

In medicine, systolic hypertension is defined as an elevated systolic blood pressure (SBP). If the systolic blood pressure is elevated (>140) with a normal (<90) diastolic blood pressure (DBP), it is called isolated systolic hypertension. Eighty percent of people with systolic hypertension are over the age of 65 years old.

Prehypertension, also known as high normal blood pressure and borderline hypertensive (BH), is a medical classification for cases where a person's blood pressure is elevated above optimal or normal, but not to the level considered hypertension. Prehypertension is now referred to as "elevated blood pressure" by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA). The ACC/AHA define elevated blood pressure as readings with a systolic pressure from 120 to 129 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure under 80 mm Hg, and the European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension (ESC/ESH) define "high normal blood pressure" as readings with a systolic pressure from 130 to 139 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure 85-89 mm Hg. Readings greater than or equal to 130/80 mm Hg are considered hypertension by ACC/AHA and if greater than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg by ESC/ESH.

Complications of hypertension are clinical outcomes that result from persistent elevation of blood pressure. Hypertension is a risk factor for all clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis since it is a risk factor for atherosclerosis itself. It is an independent predisposing factor for heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, kidney disease, and peripheral arterial disease. It is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, in industrialized countries.

Orthostatic hypertension is a medical condition consisting of a sudden and abrupt increase in blood pressure (BP) when a person stands up. Orthostatic hypertension is diagnosed by a rise in systolic BP of 20 mmHg or more when standing. Orthostatic diastolic hypertension is a condition in which the diastolic BP raises to 98 mmHg or over in response to standing, but this definition currently lacks clear medical consensus, so is subject to change. Orthostatic hypertension involving the systolic BP is known as systolic orthostatic hypertension.

The modern history of hypertension begins with the understanding of the cardiovascular system based on the work of physician William Harvey (1578–1657), who described the circulation of blood in his book De motu cordis. The English clergyman Stephen Hales made the first published measurement of blood pressure in 1733. Descriptions of what would come to be called hypertension came from, among others, Thomas Young in 1808 and especially Richard Bright in 1836. Bright noted a link between cardiac hypertrophy and kidney disease, and subsequently kidney disease was often termed Bright's disease in this period. In 1850 George Johnson suggested that the thickened blood vessels seen in the kidney in Bright's disease might be an adaptation to elevated blood pressure. William Senhouse Kirkes in 1855 and Ludwig Traube in 1856 also proposed, based on pathological observations, that elevated pressure could account for the association between left ventricular hypertrophy to kidney damage in Bright's disease. Samuel Wilks observed that left ventricular hypertrophy and diseased arteries were not necessarily associated with diseased kidneys, implying that high blood pressure might occur in people with healthy kidneys; however, the first report of elevated blood pressure in a person without evidence of kidney disease was made by Frederick Akbar Mahomed in 1874 using a sphygmograph. The concept of hypertensive disease as a generalized circulatory disease was taken up by Sir Clifford Allbutt, who termed the condition "hyperpiesia". However, hypertension as a medical entity really came into being in 1896 with the invention of the cuff-based sphygmomanometer by Scipione Riva-Rocci in 1896, which allowed blood pressure to be measured in the clinic. In 1905, Nikolai Korotkoff improved the technique by describing the Korotkoff sounds that are heard when the artery is ausculted with a stethoscope while the sphygmomanometer cuff is deflated. Tracking serial blood pressure measurements was further enhanced when Donal Nunn invented an accurate fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer device in 1981.

Hypertensive disease of pregnancy, also known as maternal hypertensive disorder, is a group of high blood pressure disorders that include preeclampsia, preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and chronic hypertension.

Hypertension is managed using lifestyle modification and antihypertensive medications. Hypertension is usually treated to achieve a blood pressure of below 140/90 mmHg to 160/100 mmHg. According to one 2003 review, reduction of the blood pressure by 5 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 34% and of ischaemic heart disease by 21% and reduce the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular disease.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Varon J, Elliott WJ (17 November 2021). Bakris GL, White WB, Forman JP (eds.). "Management of severe asymptomatic hypertension (hypertensive urgencies) in adults". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- 1 2 3 Pak KJ, Hu T, Fee C, Wang R, Smith M, Bazzano LA (2014). "Acute hypertension: a systematic review and appraisal of guidelines". The Ochsner Journal. 14 (4): 655–663. PMC 4295743 . PMID 25598731.

- 1 2 Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. (October 2018). "2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension". Journal of Hypertension. 36 (10): 1953–2041. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940. PMID 30234752.

- ↑ Kitiyakara C, Guzman NJ (January 1998). "Malignant hypertension and hypertensive emergencies". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 9 (1): 133–142. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V91133 . PMID 9440098.

- ↑ Henderson AD, Biousse V, Newman NJ, Lamirel C, Wright DW, Bruce BB (December 2012). "Grade III or Grade IV Hypertensive Retinopathy with Severely Elevated Blood Pressure". The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 13 (6): 529–534. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.10.6755. PMC 3555579 . PMID 23359839.

- ↑ Shantsila A, Lip GY (June 2017). "Malignant Hypertension Revisited-Does This Still Exist?". American Journal of Hypertension. 30 (6): 543–549. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx008 . PMID 28200072.

- 1 2 Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. (May 2003). "The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report". JAMA. 289 (19): 2560–2572. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PMID 12748199.

- 1 2 Makó K, Ureche C, Mures T, Jeremiás Z (9 June 2018). "An Updated Review of Hypertensive Emergencies and Urgencies". Journal of Cardiovascular Emergencies. 4 (2): 73–83. doi: 10.2478/jce-2018-0013 .

- ↑ Yang JY, Chiu S, Krouss M (May 2018). "Overtreatment of Asymptomatic Hypertension-Urgency Is Not an Emergency: A Teachable Moment". JAMA Internal Medicine. 178 (5): 704–705. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0126. PMID 29482197.

- ↑ Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Sun X, Johannes RS, Gupta V, Tabak YP (March 2012). "Severe acute hypertension among inpatients admitted from the emergency department". Journal of Hospital Medicine. 7 (3): 203–210. doi: 10.1002/jhm.969 . PMID 22038891.

- ↑ Preston RA, Baltodano NM, Cienki J, Materson BJ (April 1999). "Clinical presentation and management of patients with uncontrolled, severe hypertension: results from a public teaching hospital". Journal of Human Hypertension. 13 (4): 249–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000796 . PMID 10333343.