Related Research Articles

Liquidation is the process in accounting by which a company is brought to an end. The assets and property of the business are redistributed. When a firm has been liquidated, it is sometimes referred to as wound-up or dissolved, although dissolution technically refers to the last stage of liquidation. The process of liquidation also arises when customs, an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting and safeguarding customs duties, determines the final computation or ascertainment of the duties or drawback accruing on an entry.

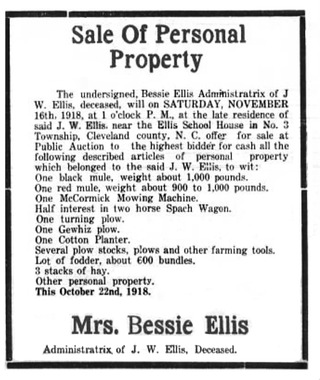

An estate sale or estate liquidation is a sale or auction to dispose of a substantial portion of the materials owned by a person who is recently deceased or who must dispose of their personal property to facilitate a move.

In finance, a floating charge is a security interest over a fund of changing assets of a company or other legal person. Unlike a fixed charge, which is created over ascertained and definite property, a floating charge is created over property of an ambulatory and shifting nature, such as receivables and stock.

Wrongful trading is a type of civil wrong found in UK insolvency law, under Section 214 Insolvency Act 1986. It was introduced to enable contributions to be obtained for the benefit of creditors from those responsible for mismanagement of the insolvent company. Under Australian insolvency law the equivalent concept is called "insolvent trading".

In law, a liquidator is the officer appointed when a company goes into winding-up or liquidation who has responsibility for collecting in all of the assets under such circumstances of the company and settling all claims against the company before putting the company into dissolution. Liquidator is a person officially appointed to 'liquidate' a company or firm. Their duty is to ascertain and settle the liabilities of a company or a firm. If there are any surplus, then those are distributed to the contributories.

United Kingdom insolvency law regulates companies in the United Kingdom which are unable to repay their debts. While UK bankruptcy law concerns the rules for natural persons, the term insolvency is generally used for companies formed under the Companies Act 2006. Insolvency means being unable to pay debts. Since the Cork Report of 1982, the modern policy of UK insolvency law has been to attempt to rescue a company that is in difficulty, to minimise losses and fairly distribute the burdens between the community, employees, creditors and other stakeholders that result from enterprise failure. If a company cannot be saved it is liquidated, meaning that the assets are sold off to repay creditors according to their priority. The main sources of law include the Insolvency Act 1986, the Insolvency Rules 1986, the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986, the Employment Rights Act 1996 Part XII, the EU Insolvency Regulation, and case law. Numerous other Acts, statutory instruments and cases relating to labour, banking, property and conflicts of laws also shape the subject.

Stanford International Bank was a bank based in the Caribbean, which operated from 1986 to 2009 when it went into receivership. It was an affiliate of the Stanford Financial Group and failed when its parent was seized by United States authorities in early 2009 as part of the investigation into Allen Stanford.

Re Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA [1998] AC 214 is a UK insolvency law case, concerning the taking of a security interest over a company's assets and priority of creditors in a company winding up.

South African property law regulates the "rights of people in or over certain objects or things." It is concerned, in other words, with a person's ability to undertake certain actions with certain kinds of objects in accordance with South African law. Among the formal functions of South African property law is the harmonisation of individual interests in property, the guarantee and protection of individual rights with respect to property, and the control of proprietary management relationships between persons, as well as their rights and obligations. The protective clause for property rights in the Constitution of South Africa stipulates those proprietary relationships which qualify for constitutional protection. The most important social function of property law in South Africa is to manage the competing interests of those who acquire property rights and interests. In recent times, restrictions on the use of and trade in private property have been on the rise.

First National Bank of SA Ltd v Lynn NO and Others is an important case in South African contract law, especially in the area of cession. It was heard in the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court by Joubert JA, Nestadt JA, Van den Heever JA, Olivier JA and Van Coller AJA on 19 September 1995, with judgment passed on 29 November. M. Tselentis SC was counsel for the appellant; Malcolm Wallis SC appeared for the respondents.

Buchler v Talbot[2004] UKHL 9 is a UK insolvency law case, concerning the priority of claims in a liquidation. Under English law at the time the expenses of liquidation took priority over the preferred creditors, and the preferred creditors took priority over the claims of the holder of a floating charge. However, a crystallised floating charge theoretically took priority over the liquidation expenses. Accordingly the courts had to try and reconcile the apparent triangular conflict between priorities.

Cayman Islands bankruptcy law is principally codified in five statutes and statutory instruments:

Australian insolvency law regulates the position of companies which are in financial distress and are unable to pay or provide for all of their debts or other obligations, and matters ancillary to and arising from financial distress. The law in this area is principally governed by the Corporations Act 2001. Under Australian law, the term insolvency is usually used with reference to companies, and bankruptcy is used in relation to individuals. Insolvency law in Australia tries to seek an equitable balance between the competing interests of debtors, creditors and the wider community when debtors are unable to meet their financial obligations. The aim of the legislative provisions is to provide:

Hong Kong insolvency law regulates the position of companies which are in financial distress and are unable to pay or provide for all of their debts or other obligations, and matters ancillary to and arising from financial distress. The law in this area is now primarily governed by the Companies Ordinance and the Companies Rules. Prior to 2012 Cap 32 was called the Companies Ordinance, but when the Companies Ordinance came into force in 2014, most of the provisions of Cap 32 were repealed except for the provisions relating to insolvency, which were retained and the statute was renamed to reflect its new principal focus.

Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v Krys[2014] UKPC 41 was a decision of the Privy Council on appeal from the British Virgin Islands relating to an anti-suit injunction in connection with an insolvent liquidation being conducted by the British Virgin Islands courts.

Ayerst v C&K (Construction) Ltd [1976] AC 167 was a decision of the House of Lords relating to revenue law and insolvency law which confirmed that where a company goes into insolvent liquidation it ceases to be the beneficial owner of its assets, and the liquidator holds those assets on a special "statutory trust" for the company's creditors.

Brooks v Armstrong[2016] EWHC 2289 (Ch), [2016] All ER (D) 117 (Nov) is a UK insolvency law case on wrongful trading under section 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986.

Re MC Bacon Ltd [1991] Ch 127 is a UK insolvency law case relating specifically to the recovery the legal costs of the liquidator in relation to an application to set aside a floating charge as an unfair preference.

Akers v Samba Financial Group[2017] UKSC 6, [2017] AC 424 is a judicial decision of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom relating to the conflict of laws, trust law and insolvency law.

Byers v Saudi National Bank[2024] UKSC 51 is a decision of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in the long running litigation between the liquidators of SAAD Investments Company Limited and various parties relating to the alleged defrauding of the insolvent company by one of its principals.