Related Research Articles

Shamanism or samanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world for the purpose of healing, divination, or to aid human beings in some other way.

Psychopomps are creatures, spirits, angels, demons, or deities in many religions whose responsibility is to escort newly deceased souls from Earth to the afterlife.

In traditional Sámi music songs and joiks are important musical expressions of the Sámi people and Sámi languages. The Sámi also use a variety of musical instruments, some unique to the Sámi, some traditional Scandinavian, and some modern introductions.

A joik or yoik is a traditional form of song in Sámi music performed by the Sámi people of Sapmi in Northern Europe. A performer of joik is called a joikaaja, a joiker or jojkare. Originally, joik referred to only one of several Sami singing styles, but in English the word is often used to refer to all types of traditional Sami singing. As an art form, each joik is meant to reflect or evoke a person, animal, or place.

The Taimyr Peninsula is a peninsula in the Far North of Russia, in the Siberian Federal District, that forms the northernmost part of the mainland of Eurasia. Administratively it is part of the Krasnoyarsk Krai Federal subject of Russia.

Kets are a Yeniseian-speaking people in Siberia. During the Russian Empire, they were known as Ostyaks, without differentiating them from several other Siberian people. Later, they became known as Yenisei Ostyaks because they lived in the middle and lower basin of the Yenisei River in the Krasnoyarsk Krai district of Russia. The modern Kets lived along the eastern middle stretch of the river before being assimilated politically into Russia between the 17th and 19th centuries. According to the 2010 census, there were 1,220 Kets in Russia. According to the 2021 census, this number had declined to 1,088.

Tadibya is the mediator between the ordinary world and the upper- and underworlds of the spirits among the Nenets people. The Nenets rank their shamans by their spiritual attachment and function as well as their experience.

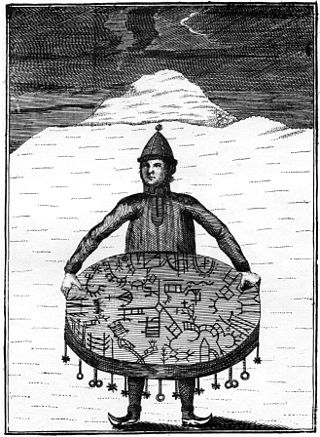

A noaidi is a shaman of the Sami people in the Nordic countries, playing a role in Sámi religious practices. Most noaidi practices died out during the 17th century, most likely because they resisted Christianization of the Sámi people and the king's authority. Their actions were referred to in courts as "magic" or "sorcery". Several Sámi shamanistic beliefs and practices are similar to those of some Siberian cultures.

Prehistoric music is a term in the history of music for all music produced in preliterate cultures (prehistory), beginning somewhere in very late geological history. Prehistoric music is followed by ancient music in different parts of the world, but still exists in isolated areas. However, it is more common to refer to the "prehistoric" music which still survives as folk, indigenous or traditional music. Prehistoric music is studied alongside other periods within music archaeology.

Natural sounds are any sounds produced by non-human organisms as well as those generated by natural, non-biological sources within their normal soundscapes. It is a category whose definition is open for discussion. Natural sounds create an acoustic space.

A large minority of people in North Asia, particularly in Siberia, follow the religio-cultural practices of shamanism. Some researchers regard Siberia as the heartland of shamanism.

Hungarian mythology includes the myths, legends, folk tales, fairy tales and gods of the Hungarians.

Masks among Eskimo peoples served a variety of functions. Masks were made out of driftwood, animal skins, bones and feathers. They were often painted using bright colors. There are archeological miniature maskettes made of walrus ivory, dating from early Paleo-Eskimo and from early Dorset culture period.

Soul dualism, also called dualistic pluralism or multiple souls, is a range of beliefs that a person has two or more kinds of souls. In many cases, one of the souls is associated with body functions and the other one can leave the body. Sometimes the plethora of soul types can be even more complex. Sometimes, a shaman's "free soul" may be held to be able to undertake a spirit journey.

Traditional Alaskan Native religion involves mediation between people and spirits, souls, and other immortal beings. Such beliefs and practices were once widespread among Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Northwest Coastal Indian cultures, but today are less common. They were already in decline among many groups when the first major ethnological research was done. For example, at the end of the 19th century, Sagdloq, the last medicine man among what were then called in English, "Polar Eskimos", died; he was believed to be able to travel to the sky and under the sea, and was also known for using ventriloquism and sleight-of-hand.

Hungarian shamanism is discovered through comparative methods in ethnology, designed to analyse and search ethnographic data of Hungarian folktales, songs, language, comparative cultures, and historical sources.

The imitation of natural sounds in various cultures is a diverse phenomenon and can fill in various functions. In several instances, it is related to the belief system. It may serve also such practical goals as luring in the hunt; or entertainment.

Elements of a Proto-Uralic religion can be recovered from reconstructions of the Proto-Uralic language.

Shamanic music is ritualistic music used in religious and spiritual ceremonies associated with the practice of shamanism. Shamanic music makes use of various means of producing music, with an emphasis on voice and rhythm. It can vary based on cultural, geographic, and religious influences.

Shamanism is a religious practice present in various cultures and religions around the world. Shamanism takes on many different forms, which vary greatly by region and culture and are shaped by the distinct histories of its practitioners.

References

- Deschênes, Bruno (2002). "Inuit Throat-Singing". Musical Traditions. The Magazine for Traditional Music Throughout the World.

- Diószegi, Vilmos (1960). Sámánok nyomában Szibéria földjén. Egy néprajzi kutatóút története. Terebess Ázsia E-Tár (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó.

- This book has been translated to English: Diószegi, Vilmos (1968). Tracing shamans in Siberia. The story of an ethnographical research expedition. Translated from Hungarian by Anita Rajkay Babó. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications.

- Eliade, Mircea (1983). Le chamanisme et les techniques archaïques de'l extase (in French). Paris: Éditions Payot.

- This book has been translated to Hungarian: Eliade, Mircea (2001). A samanizmus. Az extázis ősi technikái. Osiris könyvtár (in Hungarian). Budapest: Osiris. ISBN 963-379-755-1.

- Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában[Shamans in Eurasia] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3.

- This book is published also in German, Estonian and Finnish. Site of publisher with short description on the book (in Hungarian) Archived 2010-01-02 at the Wayback Machine .

- Hoppál, Mihály (2006). "Music of Shamanic Healing" (PDF). In Kilger, Gerhard (ed.). Macht Musik. Musik als Glück und Nutzen für das Leben. Köln: Wienand Verlag. ISBN 3-87909-865-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2007.

- Lintrop, Aarno. "The Clean Tent Rite". Studies in Siberian shamanism and religions of the Finno-Ugric peoples.

- Nattiez, Jean Jacques; Research Group in Musical Semiotics, Faculty of Music, University of Montreal (2014). Inuit Games and Songs • Chants et Jeux des Inuit. Musiques & musiciens du monde • Musics & musicians of the world. Montreal. OCLC 892647446.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)- These songs are available online from the ethnopoetics website curated by Jerome Rothenberg.

- Somby, Ánde (1995). "Joik and the theory of knowledge". Archived from the original on 2008-03-25.

- Szomjas-Schiffert, György (1996). Lapp sámánok énekes hagyománya • Singing tradition of Lapp shamans (in Hungarian and English). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-6940-X.

- Vitebsky, Piers (1995). The shaman: voyages of the soul trance, ecstasy and healing from Siberia to the Amazon. Living Wisdom. Duncan Baird. ISBN 9781903296189.

- Translated into Hungarian: Vitebsky, Piers (1996). A sámán[The shaman]. Bölcsesség • hit • mítosz (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub • Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963-208-361-X.

- Voigt, Vilmos (1966). A varázsdob és a látó asszonyok. Lapp népmesék[The magic drum and the clairvoyant women. Sami folktales]. Népek meséi (Folktales) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó.