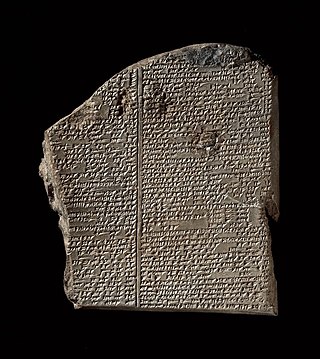

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

Folklore is the whole of oral traditions shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes tales, myths, legends, proverbs, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. They include material culture, such as traditional building styles common to the group. Folklore also includes customary lore, taking actions for folk beliefs, and the forms and rituals of celebrations such as Christmas, weddings, folk dances, and initiation rites. Each one of these, either singly or in combination, is considered a folklore artifact or traditional cultural expression. Just as essential as the form, folklore also encompasses the transmission of these artifacts from one region to another or from one generation to the next. Folklore is not something one can typically gain from a formal school curriculum or study in the fine arts. Instead, these traditions are passed along informally from one individual to another, either through verbal instruction or demonstration. The academic study of folklore is called folklore studies or folkloristics, and it can be explored at the undergraduate, graduate, and Ph.D. levels.

Poetry, also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. A poem is a literary composition, written by a poet, using this principle.

Dell Hathaway Hymes was a linguist, sociolinguist, anthropologist, and folklorist who established disciplinary foundations for the comparative, ethnographic study of language use. His research focused upon the languages of the Pacific Northwest. He was one of the first to call the fourth subfield of anthropology "linguistic anthropology" instead of "anthropological linguistics". The terminological shift draws attention to the field's grounding in anthropology rather than in what, by that time, had already become an autonomous discipline (linguistics). In 1972 Hymes founded the journal Language in Society and served as its editor for 22 years.

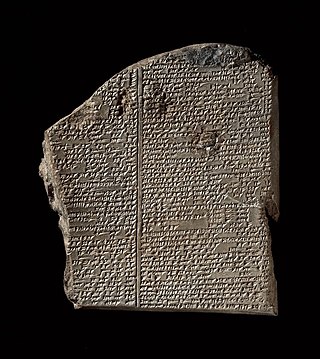

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. The transmission is through speech or song and may include folktales, ballads, chants, prose or poetry. In this way, it is possible for a society to transmit oral history, oral literature, oral law and other knowledge across generations without a writing system, or in parallel to a writing system. Religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Catholicism, and Jainism, for example, have used an oral tradition, in parallel to a writing system, to transmit their canonical scriptures, rituals, hymns and mythologies from one generation to the next.

Popol Vuh is a text recounting the mythology and history of the Kʼicheʼ people of Guatemala, one of the Maya peoples who also inhabit the Mexican states of Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo, as well as areas of Belize, Honduras and El Salvador.

Linguistic anthropology is the interdisciplinary study of how language influences social life. It is a branch of anthropology that originated from the endeavor to document endangered languages and has grown over the past century to encompass most aspects of language structure and use.

Jerome Rothenberg is an American poet, translator and anthologist, noted for his work in the fields of ethnopoetics and performance poetry.

Folklore studies is the branch of anthropology devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currency in the 1950s to distinguish the academic study of traditional culture from the folklore artifacts themselves. It became established as a field across both Europe and North America, coordinating with Volkskunde (German), folkeminner (Norwegian), and folkminnen (Swedish), among others.

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used varying descriptions for oral literature or folk literature. A broad conceptualization refers to it as literature characterized by oral transmission and the absence of any fixed form. It includes the stories, legends, and history passed through generations in a spoken form.

Zuni is a language of the Zuni people, indigenous to western New Mexico and eastern Arizona in the United States. It is spoken by around 9,500 people, especially in the vicinity of Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico, and much smaller numbers in parts of Arizona.

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

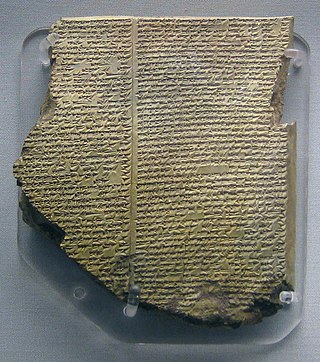

Poetry as an oral art form likely predates written text. The earliest poetry is believed to have been recited or sung, employed as a way of remembering oral history, genealogy, and law. Poetry is often closely related to musical traditions, and the earliest poetry exists in the form of hymns, and other types of song such as chants. As such poetry is a verbal art. Many of the poems surviving from the ancient world are recorded prayers, or stories about religious subject matter, but they also include historical accounts, instructions for everyday activities, love songs, and fiction.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to poetry:

Folk poetry is poetry that is part of a society's folklore, usually part of their oral tradition. When sung, folk poetry becomes a folk song.

Dennis Ernest Tedlock was an ethnopoeticist, linguist, translator, and poet. He was a leading expert of Mayan language, culture, and arts, best known for his definitive translation of the Mayan text, Popul Vuh, for which he was awarded the PEN translation prize. He co-founded the method of ethnopoetics with Jerome Rothenburg in the late 1960s.

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose, fiction, drama, poetry, and including both print and digital writing. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature, also known as orature much of which has been transcribed. Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.

Alcheringa was a magazine of ethnopoetics published between 1970 and 1980. It was edited by Dennis Tedlock and by Jerome Rothenberg, proponents of the ethnopoetics movement. The magazine was published by Boston University.

Jan Blommaert was a Belgian sociolinguist and linguistic anthropologist, Professor of Language, Culture and Globalization and Director of the Babylon Center at Tilburg University, the Netherlands. He also held appointments at Ghent University (Belgium) and University of the Western Cape. He was considered to be one of the world's most prominent sociolinguists and linguistic anthropologists, who had contributed substantially to sociolinguistic globalization theory that focuses on historical as well as contemporary patterns of the spread of languages and forms of literacy, and on lasting and new forms of inequality emerging from globalization processes.

John Barre Toelken was an award-winning American folklorist, noted for his study of Native American material and oral traditions.