The conservation and restoration of cultural property focuses on protection and care of cultural property, including artworks, architecture, archaeology, and museum collections. Conservation activities include preventive conservation, examination, documentation, research, treatment, and education. This field is closely allied with conservation science, curators and registrars.

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay further if kept in cool and dry conditions. Some authorities restrict the use of the term to bodies deliberately embalmed with chemicals, but the use of the word to cover accidentally desiccated bodies goes back to at least the early 17th century.

The Tollund Man is a naturally mummified corpse of a man who lived during the 5th century BC, during the period characterised in Scandinavia as the Pre-Roman Iron Age. He was found in 1950, preserved as a bog body, near Silkeborg on the Jutland peninsula in Denmark. The man's physical features were so well preserved that he was mistaken for a recent murder victim. Twelve years before his discovery, another bog body, Elling Woman, was found in the same bog.

A bog body is a human cadaver that has been naturally mummified in a peat bog. Such bodies, sometimes known as bog people, are both geographically and chronologically widespread, having been dated to between 8000 BCE and the Second World War. The unifying factor of the bog bodies is that they have been found in peat and are partially preserved; however, the actual levels of preservation vary widely from perfectly preserved to mere skeletons.

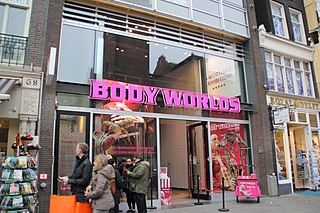

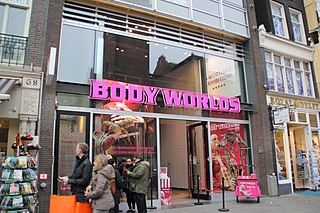

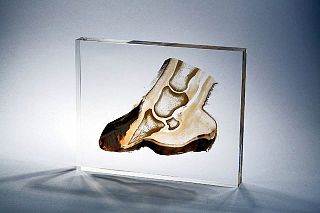

Body Worlds is a traveling exposition of dissected human bodies, animals, and other anatomical structures of the body that have been preserved through the process of plastination. Gunther von Hagens developed the preservation process which "unite[s] subtle anatomy and modern polymer chemistry", in the late 1970s.

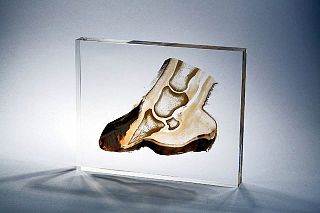

Plastination is a technique or process used in anatomy to preserve bodies or body parts, first developed by Gunther von Hagens in 1977. The water and fat are replaced by certain plastics, yielding specimens that can be touched, do not smell or decay, and even retain most properties of the original sample.

Disposal of human corpses, also called final disposition, is the practice and process of dealing with the remains of a deceased human being. Disposal methods may need to account for the fact that soft tissue will decompose relatively rapidly, while the skeleton will remain intact for thousands of years under certain conditions.

Post-excavation analysis constitutes processes that are used to study archaeological materials after an excavation is completed. Since the advent of "New Archaeology" in the 1960s, the use of scientific techniques in archaeology has grown in importance. This trend is directly reflected in the increasing application of the scientific method to post-excavation analysis. The first step in post-excavation analysis should be to determine what one is trying to find out and what techniques can be used to provide answers. Techniques chosen will ultimately depend on what type of artifact(s) one wishes to study. This article outlines processes for analyzing different artifact classes and describes popular techniques used to analyze each class of artifact. Keep in mind that archaeologists frequently alter or add techniques in the process of analysis as observations can alter original research questions.

With respect to cultural property, conservation science is the interdisciplinary study of the conservation of art, architecture, technical art history and other cultural works through the use of scientific inquiry. General areas of research include the technology and structure of artistic and historic works. In other words, the materials and techniques from which cultural, artistic and historic objects are made. There are three broad categories of conservation science with respect to cultural heritage: understanding the materials and techniques used by artists, study of the causes of deterioration, and improving techniques and materials for examination and treatment. Conservation science includes aspects of materials science, chemistry, physics, biology, and engineering, as well as art history and anthropology. Institutions such as the Getty Conservation Institute specialize in publishing and disseminating information relating to both tools used for and outcomes of conservation science research, as well as recent discoveries in the field.

Skeletonization is the state of a dead organism after undergoing decomposition. Skeletonization refers to the final stage of decomposition, during which the last vestiges of the soft tissues of a corpse or carcass have decayed or dried to the point that the skeleton is exposed. By the end of the skeletonization process, all soft tissue will have been eliminated, leaving only disarticulated bones.

A conservator-restorer is a professional responsible for the preservation of artistic and cultural artifacts, also known as cultural heritage. Conservators possess the expertise to preserve cultural heritage in a way that retains the integrity of the object, building or site, including its historical significance, context and aesthetic or visual aspects. This kind of preservation is done by analyzing and assessing the condition of cultural property, understanding processes and evidence of deterioration, planning collections care or site management strategies that prevent damage, carrying out conservation treatments, and conducting research. A conservator's job is to ensure that the objects in a museum's collection are kept in the best possible condition, as well as to serve the museum's mission to bring art before the public.

Bird collections are curated repositories of scientific specimens consisting of birds and their parts. They are a research resource for ornithology, the science of birds, and for other scientific disciplines in which information about birds is useful. These collections are archives of avian diversity and serve the diverse needs of scientific researchers, artists, and educators. Collections may include a variety of preparation types emphasizing preservation of feathers, skeletons, soft tissues, or (increasingly) some combination thereof. Modern collections range in size from small teaching collections, such as one might find at a nature reserve visitor center or small college, to large research collections of the world's major natural history museums, the largest of which contain hundreds of thousands of specimens. Bird collections function much like libraries, with specimens arranged in drawers and cabinets in taxonomic order, curated by scientists who oversee the maintenance, use, and growth of collections and make them available for study through visits or loans.

Calceology is the study of footwear, especially historical footwear whether as archaeology, shoe fashion history, or otherwise. It is not yet formally recognized as a field of research. Calceology comprises the examination, registration, research and conservation of leather shoe fragments. A wider definition includes the general study of the ancient footwear, its social and cultural history, technical aspects of pre-industrial shoemaking and associated leather trades, as well as reconstruction of archaeological footwear.

In archaeology, waterlogging refers to the long-term exclusion of air by groundwater, which creates an anaerobic environment that can preserve artifacts perfectly. Such waterlogging preserves perishable artifacts. Thus, in a site which has been waterlogged since the archaeological horizon was deposited, exceptional insight may be obtained by study of artifacts made of leather, wood, textile or similar materials. 75-90% of the archaeological remains at wetland sites are found to be organic material. Tree rings found from logs that have been preserved allow archaeologists to accurately date sites. Wetland sites include all those found in lakes, swamps, marshes, fens, and peat bogs.

Conservation and restoration of metals is the activity devoted to the protection and preservation of historical and archaeological objects made partly or entirely of metal. In it are included all activities aimed at preventing or slowing deterioration of items, as well as improving accessibility and readability of the objects of cultural heritage. Despite the fact that metals are generally considered as relatively permanent and stable materials, in contact with the environment they deteriorate gradually, some faster and some much slower. This applies especially to archaeological finds.

The conservation and restoration of musical instruments is performed by conservator-restorers who are professionals, properly trained to preserve or protect historical and current musical instruments from past or future damage or deterioration. Because musical instruments can be made entirely of, or simply contain, a wide variety of materials such as plastics, woods, metals, silks, and skin, to name a few, a conservator should be well-trained in how to properly examine the many types of construction materials used in order to provide the highest level or preventive and restorative conservation.

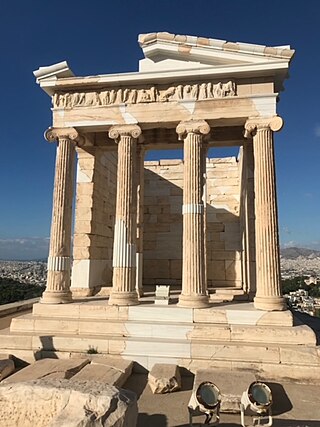

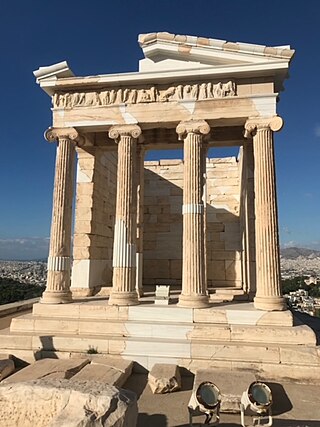

The conservation and restoration of archaeological sites is the collaborative effort between archaeologists, conservators, and visitors to preserve an archaeological site, and if deemed appropriate, to restore it to its previous state. Considerations about aesthetic, historic, scientific, religious, symbolic, educational, economic, and ecological values all need to be assessed prior to deciding the methods of conservation or needs for restoration. The process of archaeology is essentially destructive, as excavation permanently changes the nature and context of the site and the associated information. Therefore, archaeologists and conservators have an ethical responsibility to care for and conserve the sites they put at risk.

Conservation-restoration of bone, horn, and antler objects involves the processes by which the deterioration of objects either containing or made from bone, horn, and antler is contained and prevented. Their use has been documented throughout history in many societal groups as these materials are durable, plentiful, versatile, and naturally occurring/replenishing.

The conservation of taxidermy is the ongoing maintenance and preservation of zoological specimens that have been mounted or stuffed for display and study. Taxidermy specimens contain a variety of organic materials, such as fur, bone, feathers, skin, and wood, as well as inorganic materials, such as burlap, glass, and foam. Due to their composite nature, taxidermy specimens require special care and conservation treatments for the different materials.

Cultural property imaging is a necessary part of long term preservation of cultural heritage. While the physical conditions of objects will change over time, imaging serves as a way to document and represent heritage in a moment in time of the life of the item. Different methods of imaging produce results that are applicable in various circumstances. Not every method is appropriate for every object, and not every object needs to be imaged by multiple methods. In addition to preservation and conservation-related concerns, imaging can also serve to enhance research and study of cultural heritage.