Gamelan is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. The most common instruments used are metallophones played by mallets and a set of hand-played drums called kendang, which register the beat. The kemanak and gangsa are commonly used gamelan instruments in Bali. Other instruments include xylophones, bamboo flutes, a bowed instrument called a rebab, a zither-like instrument siter and vocalists named sindhen (female) or gerong (male).

Samādhi, in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yoga tradition, it is the eighth and final limb identified in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

Organology is the science of musical instruments and their classifications. It embraces study of instruments' history, instruments used in different cultures, technical aspects of how instruments produce sound, and musical instrument classification. There is a degree of overlap between organology, ethnomusicology and the branch of the science of acoustics devoted to musical instruments.

A Shinto shrine is a structure whose main purpose is to house ("enshrine") one or more kami, the deities of the Shinto religion.

A National Treasure is the most precious of Japan's Tangible Cultural Properties, as determined and designated by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. A Tangible Cultural Property is considered to be of historic or artistic value, classified either as "buildings and structures" or as "fine arts and crafts". Each National Treasure must show outstanding workmanship, a high value for world cultural history, or exceptional value for scholarship.

Material culture is the aspect of culture manifested by the physical objects and architecture of a society. The term is primarily used in archaeology and anthropology, but is also of interest to sociology, geography and history. The field considers artifacts in relation to their specific cultural and historic contexts, communities and belief systems. It includes the usage, consumption, creation and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms and rituals that the objects create or take part in.

Sampradaya, in Indian origin religions, namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, can be translated as 'tradition', 'spiritual lineage', 'sect', or 'religious system'. To ensure continuity and transmission of dharma, various sampradayas have the Guru-shishya parampara in which parampara or lineage of successive gurus (masters) and shishyas (disciples) serves as a spiritual channel and provides a reliable network of relationships that lends stability to a religious identity. Shramana is vedic term for seeker or shishya. Identification with and followership of sampradayas is not static, as sampradayas allows flexibility where one can leave one sampradaya and enter another or practice religious syncretism by simultaneously following more than one sampradaya. Samparda is a punjabi language term, used in Sikhism, for sampradayas.

Cultural heritage is the heritage of tangible and intangible heritage assets of a group or society that is inherited from past generations. Not all heritages of past generations are "heritage"; rather, heritage is a product of selection by society.

Maslaha or maslahah is a concept in shari'ah regarded as a basis of law. It forms a part of extended methodological principles of Islamic jurisprudence and denotes prohibition or permission of something, according to necessity and particular circumstances, on the basis of whether it serves the public interest of the Muslim community (ummah). In principle, maslaha is invoked particularly for issues that are not regulated by the Qur'an, the sunnah, or qiyas (analogy). The concept is acknowledged and employed to varying degrees depending on the jurists and schools of Islamic jurisprudence (maddhab). The application of the concept has become more important in modern times because of its increasing relevance to contemporary legal issues.

A conservator-restorer is a professional responsible for the preservation of artistic and cultural artifacts, also known as cultural heritage. Conservators possess the expertise to preserve cultural heritage in a way that retains the integrity of the object, building or site, including its historical significance, context and aesthetic or visual aspects. This kind of preservation is done by analyzing and assessing the condition of cultural property, understanding processes and evidence of deterioration, planning collections care or site management strategies that prevent damage, carrying out conservation treatments, and conducting research. A conservator's job is to ensure that the objects in a museum's collection are kept in the best possible condition, as well as to serve the museum's mission to bring art before the public.

Digital artifactual value, a preservation term, is the intrinsic value of a digital object, rather than the informational content of the object. Though standards are lacking, born-digital objects and digital representations of physical objects may have a value attributed to them as artifacts.

A Cultural Property is administered by the Japanese government's Agency for Cultural Affairs, and includes tangible properties ; intangible properties ; folk properties both tangible and intangible; monuments historic, scenic and natural; cultural landscapes; and groups of traditional buildings. Buried properties and conservation techniques are also protected. Together these cultural properties are to be preserved and utilized as the heritage of the Japanese people.

Vietnamese folk religion is the ethnic religion of the Vietnamese people. About 86% of the population in Vietnam are associated with this religion.

The conservation and restoration of musical instruments is performed by conservator-restorers who are professionals, properly trained to preserve or protect historical and current musical instruments from past or future damage or deterioration. Because musical instruments can be made entirely of, or simply contain, a wide variety of materials such as plastics, woods, metals, silks, and skin, to name a few, a conservator should be well-trained in how to properly examine the many types of construction materials used in order to provide the highest level or preventive and restorative conservation.

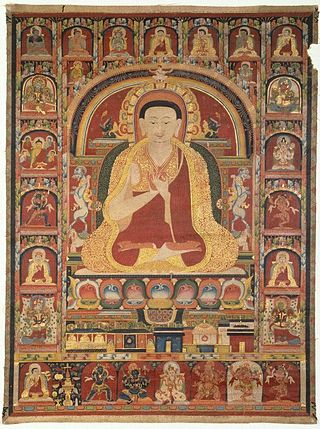

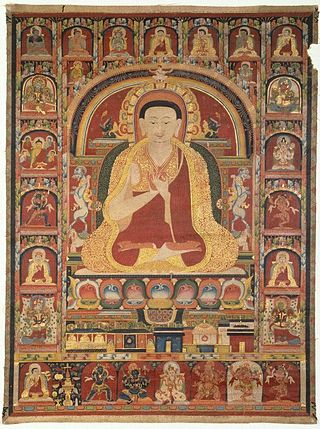

The conservation and restoration of Tibetan thangkas is the physical preservation of the traditional religious Tibetan painting form known as a thangka. When applied to thangkas of significant cultural heritage, this activity is generally undertaken by a conservator-restorer.

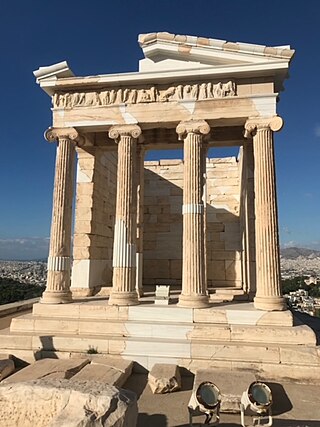

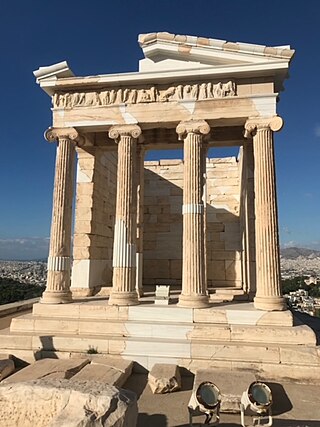

The conservation and restoration of archaeological sites is the collaborative effort between archaeologists, conservators, and visitors to preserve an archaeological site, and if deemed appropriate, to restore it to its previous state. Considerations about aesthetic, historic, scientific, religious, symbolic, educational, economic, and ecological values all need to be assessed prior to deciding the methods of conservation or needs for restoration. The process of archaeology is essentially destructive, as excavation permanently changes the nature and context of the site and the associated information. Therefore, archaeologists and conservators have an ethical responsibility to care for and conserve the sites they put at risk.

It is quite difficult to define Indonesian art, since the country is immensely diverse. The sprawling archipelago nation consists of 17.000 islands. Around 922 of those permanently inhabited, by over 1,300 ethnic groups, which speak more than 700 living languages.

The Conservation of South Asian household shrines is an activity dedicated to the preservation of household shrines from South Asia. When applied to cultural heritage, held by either museums or private collectors, this activity is generally undertaken by a conservator-restorer. South Asian shrines held in museum collections around the world are principally shrines relate to Hindu, Jain, or Buddhist households. Due to their original use and sacred nature, these shrines present unique conservation and restoration challenges for those tasked with their care.

Silken Painting of Emperor Go-Daigo is a portrait and Buddhist painting of Emperor Go-Daigo from the Nanboku-chō period. The painting was supervised by the Buddhist priest and protector of Emperor Go-Daigo, Bunkanbo Koshin. After his death, Buddhābhiṣeka opened his eyes on September 20, October 23, 1339, the fourth year of Enen4/Ryakuō, during the 57th day Buddhist memorial service..Meiji 33rd year (1900), April 7, designated as Important Cultural Property. As Emperor of Japan rather than Cloistered Emperor, he was granted the highest Abhisheka of Shingon Buddhism He was united with Vajrasattva, a Bodhisattva, as a secular emperor, and became a symbol of the unification of the royal law, Buddhism, and Shintoism under the Sanja-takusen, in which the three divine symbols were written. After the end of the Civil War of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, it was transferred to the head temple of the Tokishu sect, Shōjōkō-ji, by the 12th Yūkyō Shōnin, a cousin of Go-Daigo and the founder of the Tokishu sect. During the Sengoku period, it became an object of worship for the Tokimune sect of the time, and copies were made. Because it is directly related to the theory of kingship in the Kenmu Restoration, it is important in Art history, History of religion, and Political history. It is said to show the legitimate kingship as the protector of Vajrayana succeeding his father, Emperor Go-Uda, as well as the harmonious political and religious kingship as in the reign of Prince Shōtoku.

Sect Shinto refers to several independent organized Shinto groups that were excluded by law in 1882 from government-run State Shinto. These independent groups have more developed belief systems than mainstream Shrine Shinto, which focuses more on rituals. Many such groups are organized into the Kyōha Shintō Rengōkai. Before World War II, Sect Shinto consisted of 13 denominations, which were referred to as the 13 Shinto schools. Since then, there have been additions and withdrawals of membership.