Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a potter is also called a pottery. The definition of pottery, used by the ASTM International, is "all fired ceramic wares that contain clay when formed, except technical, structural, and refractory products". End applications include tableware, decorative ware, sanitary ware, and in technology and industry such as electrical insulators and laboratory ware. In art history and archaeology, especially of ancient and prehistoric periods, pottery often means only vessels, and sculpted figurines of the same material are called terracottas.

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi (侘び寂び) is a world view centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The aesthetic is sometimes described as one of appreciating beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete" in nature. It is prevalent in many forms of Japanese art.

Pottery and porcelain is one of the oldest Japanese crafts and art forms, dating back to the Neolithic period. Types have included earthenware, pottery, stoneware, porcelain, and blue-and-white ware. Japan has an exceptionally long and successful history of ceramic production. Earthenwares were made as early as the Jōmon period, giving Japan one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world. Japan is further distinguished by the unusual esteem that ceramics hold within its artistic tradition, owing to the enduring popularity of the tea ceremony. During the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1603), kilns throughout Japan produced ceramics with unconventional designs. In the early Edo period, the production of porcelain commenced in the Hizen-Arita region of Kyushu, employing techniques imported from Korea. These porcelain works became known as Imari wares, named after the port of Imari from which they were exported to various markets, including Europe.

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, and for applying incised decoration or rings of colour. Use of the potter's wheel became widespread throughout the Old World but was unknown in the Pre-Columbian New World, where pottery was handmade by methods that included coiling and beating.

Buncheong (Korean: 분청), or punch'ong, ware is a traditional form of Korean stoneware, with a blue-green tone. Pieces are coated with white slip (ceramics), and decorative designs are added using a variety of techniques. This style originated in the 15th century and continues in a revived form today.

Lacquerware is a Japanese craft with a wide range of fine and decorative arts, as lacquer has been used in urushi-e, prints, and on a wide variety of objects from Buddha statues to bento boxes for food.

Sue pottery was a blue-gray form of stoneware pottery fired at high temperature, which was produced in Japan and southern Korea during the Kofun, Nara, and Heian periods of Japanese history. It was initially used for funerary and ritual objects, and originated from Korea to Kyūshū. Although the roots of Sueki reach back to ancient China, its direct precursor is the grayware of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.

Iskandar Jalil is a Singapore ceramist. He was awarded the Cultural Medallion for Visual Arts in 1988.

Ceramics of Jalisco, Mexico has a history that extends far back in the pre Hispanic period, but modern production is the result of techniques introduced by the Spanish during the colonial period and the introduction of high-fire production in the 1950s and 1960s by Jorge Wilmot and Ken Edwards. Today various types of traditional ceramics such as bruñido, canelo and petatillo are still made, along with high fire types like stoneware, with traditional and nontraditional decorative motifs. The two main ceramics centers are Tlaquepaque and Tonalá, with a wide variety of products such as cookware, plates, bowls, piggy banks and many types of figures.

Openwork or open-work is a term in art history, architecture and related fields for any technique that produces decoration by creating holes, piercings, or gaps that go right through a solid material such as metal, wood, stone, pottery, cloth, leather, or ivory. Such techniques have been very widely used in a great number of cultures.

Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take varied forms, including artistic pottery, including tableware, tiles, figurines and other sculpture. As one of the plastic arts, ceramic art is a visual art. While some ceramics are considered fine art, such as pottery or sculpture, most are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramic art can be created by one person or by a group, in a pottery or a ceramic factory with a group designing and manufacturing the artware.

Boro (ぼろ) are a class of Japanese textiles that have been mended or patched together. The term is derived from the Japanese term "boroboro", meaning something tattered or repaired. The term 'boro' typically refers to cotton, linen and hemp materials, mostly hand-woven by peasant farmers, that have been stitched or re-woven together to create an often many-layered material used for warm, practical clothing.

Osamu Suzuki (1926-2001) was a Japanese ceramicist and one of the co-founders of the artist group Sōdeisha, a Japanese avant-garde ceramics movement that arose following the end of the Second World War and served as a counter to the traditional forms and styles in modern Japanese ceramics, such as Mingei. Working in both iron-rich stoneware and porcelain, Suzuki developed his style considerably over the course of his career, beginning with functional vessels in his early work, and spanning to fully sculptural works in the latter half of his career. Suzuki has been described by The Japan Times as "one of Japan's most important ceramic artists of the 20th century."

Koishiwara ware, formerly known as Nakano ware, is a type of Japanese pottery traditionally from Koishiwara, Fukuoka Prefecture in western Japan. Koishiwara ware consists of utility vessels such as bowls, plates, and tea cups. The style is often slipware.

The conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery is a sub-section of the broader topic of conservation and restoration of ceramic objects. Ancient Greek pottery is one of the most commonly found types of artifacts from the ancient Greek world. The information learned from vase paintings forms the foundation of modern knowledge of ancient Greek art and culture. Most ancient Greek pottery is terracotta, a type of earthenware ceramic, dating from the 11th century BCE through the 1st century CE. The objects are usually excavated from archaeological sites in broken pieces, or shards, and then reassembled. Some have been discovered intact in tombs. Professional conservator-restorers, often in collaboration with curators and conservation scientists, undertake the conservation-restoration of ancient Greek pottery.

Rick Dillingham (1952–1994) was an American ceramic artist, scholar, collector and museum professional best known for his broken pot technique and scholarly publications on Pueblo pottery.

Yee Soo-kyung is a South Korean multi-disciplinary artist and sculptor best known for her Translated Vase series which utilizes the broken fragments of priceless Korean ceramics to form a new sculpture. Yee's biomorphic sculptures highlight the beauty and possibility after rupture. Her other works in installation and drawings explore psycho-spiritual introspection, cultural deconstruction, kitsch, as well as Korean traditional arts and history melded with contemporary aesthetics.

Visible mending is a form of repair work, usually on textile items, that is deliberately left visible. The dual goals of this practice are to adorn the item, and to attract attention to the fact it has been mended in some way. The latter is often a statement of critique on the consumerist idea of replacing broken items with new ones without trying to bring them back to full functionality. In other words, the repair is supposed to be a new and distinct feature of the item.

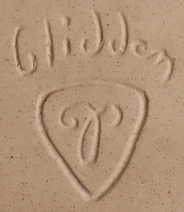

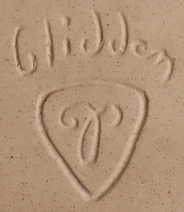

Glidden Pottery produced unique stoneware, dinnerware and artware in Alfred, New York from 1940 to 1957. The company was established by Glidden Parker, who had studied ceramics at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University. Glidden Pottery's mid-century designs combined molded stoneware forms with hand-painted decoration. The New Yorker magazine described Glidden Pottery as "distinguished by a mat surface, soft color combinations, and, in general, well-thought-out forms that one won't see duplicated in other wares". Gliddenware was sold in leading department stores across the country. Examples of Glidden Pottery can occasionally be seen in television programs from the era, such as I Love Lucy.

Kunio Nakamura is a Japanese artist and the founder of the art gallery "6jigen " based in Ogikubo, Tokyo.