Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavior, while cultural anthropology studies cultural meaning, including norms and values. The term sociocultural anthropology is commonly used today. Linguistic anthropology studies how language influences social life. Biological or physical anthropology studies the biological development of humans.

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term sociocultural anthropology includes both cultural and social anthropology traditions.

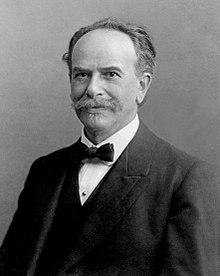

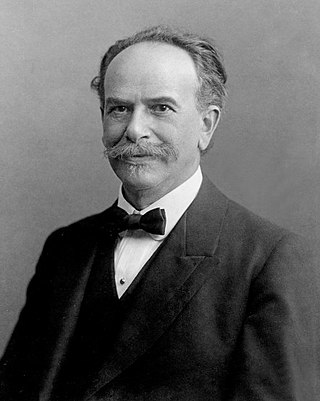

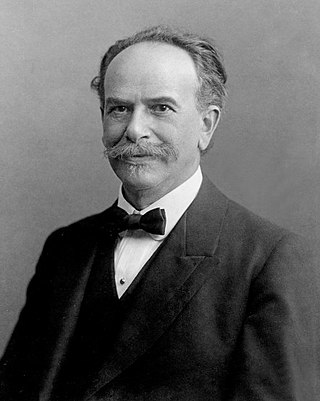

Edward Sapir was an American anthropologist-linguist, who is widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics in the United States.

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of using the standards of the particular culture involved. Since this judgment is often negative, some people also use the term to refer to the belief that one's culture is superior to, or more correct or normal than, all others—especially regarding the distinctions that define each ethnicity's cultural identity, such as language, behavior, customs, and religion. In common usage, it can also simply mean any culturally biased judgment. For example, ethnocentrism can be seen in the common portrayals of the Global South and the Global North.

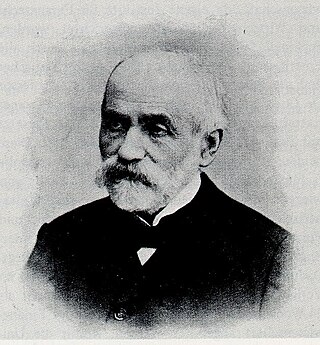

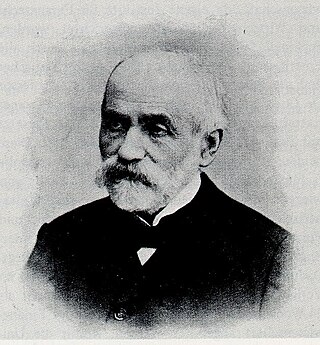

Franz Uri Boas was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical particularism and cultural relativism.

Ruth Fulton Benedict was an American anthropologist and folklorist.

Early infanticidal childrearing is a term used in the study of psychohistory that refers to infanticide in paleolithic, pre-historical, and historical hunter-gatherer tribes or societies. "Early" means early in history or in the cultural development of a society, not to the age of the child. "Infanticidal" refers to the high incidence of infants killed when compared to modern nations. The model was developed by Lloyd deMause within the framework of psychohistory as part of a seven-stage sequence of childrearing modes that describe the development attitudes towards children in human cultures The word "early" distinguishes the term from late infanticidal childrearing, identified by deMause in the more established, agricultural cultures up to the ancient world.

Cultural relativism is the view that concepts and moral values must be understood in their own cultural context and not judged according to the standards of a different culture. It asserts the equal validity of all points of view and the relative nature of truth, which is determined by an individual or their culture.

Ralph Linton was an American anthropologist of the mid-20th century, particularly remembered for his texts The Study of Man (1936) and The Tree of Culture (1955). One of Linton's major contributions to anthropology was defining a distinction between status and role.

Robert Harry Lowie was an Austrian-born American anthropologist. An expert on Indigenous peoples of the Americas, he was instrumental in the development of modern anthropology and has been described as "one of the key figures in the history of anthropology".

History of anthropology in this article refers primarily to the 18th- and 19th-century precursors of modern anthropology. The term anthropology itself, innovated as a Neo-Latin scientific word during the Renaissance, has always meant "the study of man". The topics to be included and the terminology have varied historically. At present they are more elaborate than they were during the development of anthropology. For a presentation of modern social and cultural anthropology as they have developed in Britain, France, and North America since approximately 1900, see the relevant sections under Anthropology.

Alfred Irving "Pete" Hallowell was an American anthropologist, archaeologist and businessman.

Melford Elliot Spiro was an American cultural anthropologist specializing in religion and psychological anthropology. He is known for his critiques of the pillars of contemporary anthropological theory—wholesale cultural determinism, radical cultural relativism, and virtually limitless cultural diversity—and for his emphasis on the theoretical importance of unconscious desires and beliefs in the study of stability and change in social and cultural systems, particularly in respect to the family, politics, and religion. Explicated in numerous theoretical publications, they are empirically exemplified in monographs based on his fieldwork in Ifaluk atoll in Micronesia, an Israeli kibbutz, and a village in Burma.

Historical particularism is widely considered the first American anthropological school of thought.

Regna Darnell is an American-Canadian anthropologist and professor of Anthropology and First Nations Studies at the University of Western Ontario, where she has founded the First Nations Studies Program.

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In the United States, social anthropology is commonly subsumed within cultural anthropology or sociocultural anthropology.

Herbert S. Lewis is a Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he taught from 1963 to 1998. He has conducted extensive field research in Ethiopia and Israel and worked with Oneida Indian Nation of Wisconsin. Aside from publications based on ethnographic field research he has written theoretical works about political leadership and systems, ethnicity, cultural evolution. Since the late 1990s he has published extensively about the history of anthropology, much of it offering new insights into the work and thought of Franz Boas.

Gene Weltfish was an American anthropologist and historian working at Columbia University from 1928 to 1953. She had studied with Franz Boas and was a specialist in the culture and history of the Pawnee people of the Midwest Plains. Her 1965 ethnography, The Lost Universe: Pawnee Life and Culture, is considered the authoritative work on Pawnee culture to this day.

Alexander Lesser (1902–1982) was an American anthropologist. Working in the Boasian tradition of American cultural anthropology, he adopted critical stances of several ideas of his fellow Boasians, and became known as an original and critical thinker, pioneering several ideas that later became widely accepted within anthropology.

American anthropology has culture as its central and unifying concept. This most commonly refers to the universal human capacity to classify and encode human experiences symbolically, and to communicate symbolically encoded experiences socially. American anthropology is organized into four fields, each of which plays an important role in research on culture:

- biological anthropology

- linguistic anthropology

- cultural anthropology

- archaeology