Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavior, while cultural anthropology studies cultural meaning, including norms and values. The term sociocultural anthropology is commonly used today. Linguistic anthropology studies how language influences social life. Biological or physical anthropology studies the biological development of humans.

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term sociocultural anthropology includes both cultural and social anthropology traditions.

Political ecology is the study of the relationships between political, economic and social factors with environmental issues and changes. Political ecology differs from apolitical ecological studies by politicizing environmental issues and phenomena.

Human ecology is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. The philosophy and study of human ecology has a diffuse history with advancements in ecology, geography, sociology, psychology, anthropology, zoology, epidemiology, public health, and home economics, among others.

Cultural ecology is the study of human adaptations to social and physical environments. Human adaptation refers to both biological and cultural processes that enable a population to survive and reproduce within a given or changing environment. This may be carried out diachronically, or synchronically. The central argument is that the natural environment, in small scale or subsistence societies dependent in part upon it, is a major contributor to social organization and other human institutions. In the academic realm, when combined with study of political economy, the study of economies as polities, it becomes political ecology, another academic subfield. It also helps interrogate historical events like the Easter Island Syndrome.

Environmental sociology is the study of interactions between societies and their natural environment. The field emphasizes the social factors that influence environmental resource management and cause environmental issues, the processes by which these environmental problems are socially constructed and define as social issues, and societal responses to these problems.

Julian Haynes Steward was an American anthropologist known best for his role in developing "the concept and method" of cultural ecology, as well as a scientific theory of culture change.

Ecological anthropology is a sub-field of anthropology and is defined as the "study of cultural adaptations to environments". The sub-field is also defined as, "the study of relationships between a population of humans and their biophysical environment". The focus of its research concerns "how cultural beliefs and practices helped human populations adapt to their environments, and how people used elements of their culture to maintain their ecosystems". Ecological anthropology developed from the approach of cultural ecology, and it provided a conceptual framework more suitable for scientific inquiry than the cultural ecology approach. Research pursued under this approach aims to study a wide range of human responses to environmental problems.

Historical ecology is a research program that focuses on the interactions between humans and their environment over long-term periods of time, typically over the course of centuries. In order to carry out this work, historical ecologists synthesize long-series data collected by practitioners in diverse fields. Rather than concentrating on one specific event, historical ecology aims to study and understand this interaction across both time and space in order to gain a full understanding of its cumulative effects. Through this interplay, humans adapt to and shape the environment, continuously contributing to landscape transformation. Historical ecologists recognize that humans have had world-wide influences, impact landscape in dissimilar ways which increase or decrease species diversity, and that a holistic perspective is critical to be able to understand that system.

Multilineal evolution is a 20th-century social theory about the evolution of societies and cultures. It is composed of many competing theories by various sociologists and anthropologists. This theory has replaced the older 19th century set of theories of unilineal evolution, where evolutionists were deeply interested in making generalizations.

Human behavioral ecology (HBE) or human evolutionary ecology applies the principles of evolutionary theory and optimization to the study of human behavioral and cultural diversity. HBE examines the adaptive design of traits, behaviors, and life histories of humans in an ecological context. One aim of modern human behavioral ecology is to determine how ecological and social factors influence and shape behavioral flexibility within and between human populations. Among other things, HBE attempts to explain variation in human behavior as adaptive solutions to the competing life-history demands of growth, development, reproduction, parental care, and mate acquisition. HBE overlaps with evolutionary psychology, human or cultural ecology, and decision theory. It is most prominent in disciplines such as anthropology and psychology where human evolution is considered relevant for a holistic understanding of human behavior.

Ethnoecology is the scientific study of how different groups of people living in different locations understand the ecosystems around them, and their relationships with surrounding environments.

Roy Abraham Rappaport (1926–1997) was an American anthropologist known for his contributions to the anthropological study of ritual and to ecological anthropology.

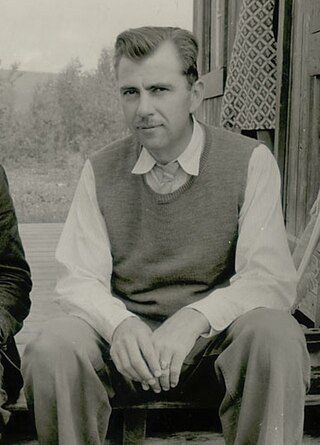

Frederick Russell Eggan was an American anthropologist best known for his innovative application of the principles of British social anthropology to the study of Native American tribes. He was the favorite student of the British social anthropologist A. R. Radcliffe-Brown during Radcliffe-Brown's years at the University of Chicago. His fieldwork was among Pueblo peoples in the southwestern U.S. Eggan later taught at Chicago himself. His students there included Sol Tax.

Andrew P. "Pete" Vayda was a Hungarian-born American anthropologist and ecologist who was a distinguished professor emeritus of anthropology and ecology at Rutgers University.

In ecology, resilience is the capacity of an ecosystem to respond to a perturbation or disturbance by resisting damage and subsequently recovering. Such perturbations and disturbances can include stochastic events such as fires, flooding, windstorms, insect population explosions, and human activities such as deforestation, fracking of the ground for oil extraction, pesticide sprayed in soil, and the introduction of exotic plant or animal species. Disturbances of sufficient magnitude or duration can profoundly affect an ecosystem and may force an ecosystem to reach a threshold beyond which a different regime of processes and structures predominates. When such thresholds are associated with a critical or bifurcation point, these regime shifts may also be referred to as critical transitions.

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) describes indigenous and other traditional knowledge of local resources. As a field of study in North American anthropology, TEK refers to "a cumulative body of knowledge, belief, and practice, evolving by accumulation of TEK and handed down through generations through traditional songs, stories and beliefs. It is concerned with the relationship of living beings with their traditional groups and with their environment." Indigenous knowledge is not a universal concept among various societies, but is referred to a system of knowledge traditions or practices that are heavily dependent on "place".

Harold Colyer Conklin was an American anthropologist who conducted extensive ethnoecological and linguistic field research in Southeast Asia and was a pioneer of ethnoscience, documenting indigenous ways of understanding and knowing the world.

Ethnoscience has been defined as an attempt "to reconstitute what serves as science for others, their practices of looking after themselves and their bodies, their botanical knowledge, but also their forms of classification, of making connections, etc.".

Susan H. Lees is a cultural anthropologist and human ecologist, and the former editor-in-chief of Human Ecology and American Anthropologist. She received her PhD from the University of Michigan and is professor emeritus of cultural anthropology, human ecology, economic anthropology, and religion at Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Susan has performed field research around the world in places such as Mexico, Peru, Brazil, and Israel on historical changes to irrigation in agriculture. Additionally, her research has been published throughout her career in University Press of America, Greenwood Press, Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd., University of North Carolina Press, and more.